Inspired by the overarching goal to strengthen the EU’s strategic autonomy, its authorities are pushing for a retail payment solution provided by European players and functioning in all member states as well as across national borders. European citizens already enjoy a wide choice of payment options.

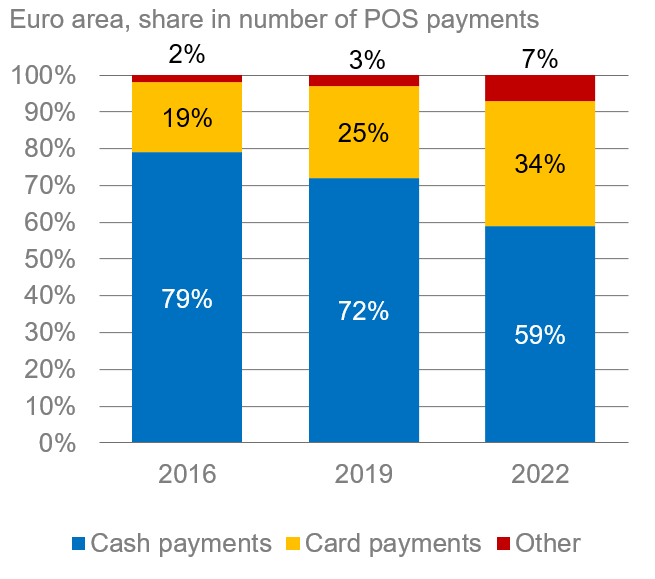

However, card and mobile/online payments are dominated by non-European providers in many countries. What is more, these are the only ones to enable euro transactions across borders within the monetary union. The only “European solution” so far which works in the entire union is euro cash – but cash usage is in decline.

Against this background, two distinct projects have emerged to build a European-run retail payment option: the European Payments Initiative (EPI) founded by banks and service providers from France, Germany, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands; and the ECB’s push for a digital euro.

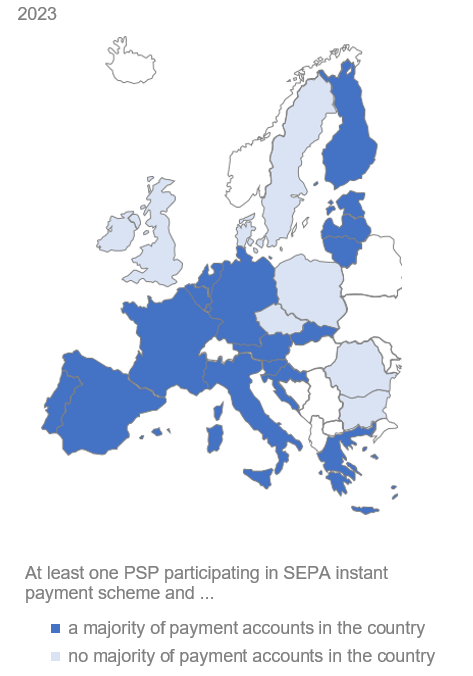

EPI will finally enable consumers to use instant payments at the point-of-sale (POS) through a digital wallet, i.e. a mobile app – to pay conveniently at the till, online and also among friends. It will take advantage of an existing infrastructure with almost full European reach: plain-vanilla current accounts and SEPA instant payment clearing and settlement will allow for real-time and more efficient transactions. Value-added services are envisaged to make the wallet more attractive. Financial institutions participating in EPI can leverage the customer base in their home countries in order to achieve positive network effects. However, sufficient reach could be the pain point of EPI. At the start, the payment service will only be available in some countries. The project is open to new members, though.

By contrast, reach will be no issue for the digital euro. Indeed, the “Regulation on the Establishment of a Digital Euro” proposed last week by the European Commission would oblige merchants to accept digital euros, and banks to offer related wallet services to consumers. However, the digital euro would not simply be another payment option. It would also be central bank-issued digital cash. As such, the issuance could cause risks to financial stability if the digital euro were to divert funding away from banks by reducing deposits. The ECB aims to minimize these risks by limiting the amount of digital euros available per user (probably at around EUR 3,000). Albeit prudent from a financial stability point of view, the holding limit could make the digital euro more complicated compared to money in regular payment accounts. Any user who wants to receive and send digital euros above the threshold will need to use the “waterfall mechanism”, which will automatically transfer such surplus amounts to and from a related bank account. But this account will already offer about the same payment services as the digital euro, with some services – especially cross-border – being provided by non-European card companies. Being default-proof central bank money might not be much of a competitive edge either as bank deposits are legally insured up to EUR 100,000. In short, a regulatory obligation to accept digital euros and to service wallets is no guarantee that consumers will use it, given state-of-the-art and less complicated alternatives.

In any case, both the market-backed and the state-led projects will enter an already vibrant and competitive payments market. On top, financial inclusion is very high in Europe, and (digital) payment growth only comes from the substitution of cash payments and general economic growth. There are no signs of market failure. Rather, policymakers are exerting pressure – implicit or explicit – to achieve political goals. In this situation, better coordination would benefit Europe. As of now, two similar payment services designed to strengthen Europe’s strategic autonomy could easily cannibalize each other.

The digital euro will hardly be issued before 2027 since the necessary legal and technical foundations are still under development. Since EPI will use an existing technical backbone, it can be brought to the market faster. In early 2024, the EPI wallet is supposed to go live in France, Germany and Belgium. These markets represent more than half of all digital payments in the euro area.

Conceivably, given greater exposure to competition, private payment service providers (PSPs) might overall be in a better and more flexible position than public authorities to tailor services to merchants’ and clients’ needs, to quickly incorporate future innovations or adjust to changing customer preferences.

Also, service levels and pricing models, as well as incentives for consumers, will be negotiated between PSPs and merchants in a competitive market. Even though EPI could threaten some of PSPs’ existing payment fee income, a market-driven approach may be more sustainable than publicly administered prices and services, as intended for the digital euro.

The proposed EU regulation would set price caps for digital euro services. Merchants will be charged by PSPs, while there will be no charges for retail clients, largely in line with current market practice. Finally, instant payments do not come with risks for financial stability as central bank-issued digital cash does.

Deutsche Bank AG

Please visit the firm link to site