Americans are all in for labor these days. According to an August 2022 Gallup poll, 71 percent of Americans approve of labor unions, up from 64 percent prior to the pandemic and the highest Gallup has recorded since 1965.

With Hollywood writers and actors on their first coordinated strike in 63 years, thousands of Los Angeles hospitality workers walking their own picket lines, and what looks to be a narrowly averted strike by 340,000 UPS workers as of July 25, union observers are calling this the “Hot Labor Summer.” Stanford Law School’s William Gould, the Charles A. Beardsley Professor of Law, Emeritus, a former chairman of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), and former chairman of the California Agricultural Relations Board, says it is more like a “Hot Labor Year,” with more hot years likely to come.

Here, Gould discusses the underlying reasons for labor’s ability to flex its muscles and some of the potential consequences, including an economic reality that isn’t always part of the discussion: how successful strikes and negotiations at unionized entities open the door to potentially huge economic advantage for non-unionized competitors.

What are some of the political, cultural, and economic factors that are bolstering the labor movement’s current strength?

There is quite clearly a revived sense of activity and energy on the part of the labor movement and that’s due to a number of other factors. One is, of course, the pandemic, which created considerable instability and dislocation for many workers. It also forced society to take account of people whose contributions had not been properly recognized in the past. I think there’s also some resentment over the fact that pandemic-era attention that was provided to some workers has since been removed.

Then there’s the element of inflation. Workers have been struggling to catch up in terms of their real wages. And you have to keep in mind the overlay to all of this has been growing inequality in our society for more than half a century. Part of that growing inequality has been attributable to the diminution of the labor movement, the declining influence of unions, and the declining number of workers that unions actually represent.

There are a number of other reasons as well, not the least of which is the advent of artificial intelligence and the huge effect that is going to have on jobs and on society in general.

So we have all of these factors at play, along with the fact that President Biden is, in my opinion, the most pro-labor president we have had since FDR.

The impact of artificial intelligence (AI) and other types of technology is taking center stage in the Hollywood strikes by the actors’ union, SAG-AFTRA and the Writers Guild of America, correct?

The use of AI has quickly become a major driver in Hollywood, but there is basically nothing to regulate its use in order to protect writers and actors. One of the reasons for the SAG-AFTRA strike was that AI was being used to recreate actors’ voices and copy their likeness without their consent. For labor, for all of us, these are really issues of first impression and it is anyone’s guess how this is going to play out.

And the impact of new technologies is a driving force behind other strikes as well, not just in Hollywood. Take the hospitality industry, where so much technological innovation has been put in place—or soon will—that substitutes for human workers. Right now, we are seeing a major hospitality worker strike in Los Angeles which is really pivotal because the workers in this industry represent a huge chunk of the people organized labor must reach. They’re the impoverished, the marginalized, the undocumented.

Do you anticipate more labor action after this “Hot Labor Summer” and what is the significance of some of these strikes?

The contract between the United Auto Workers and the Big Three American auto manufacturers will expire this fall, and that could result in another major strike. They are looking for answers to the problem of layoffs, which in the automobile industry and manufacturing have really destabilized our country and huge regions of the Midwest and Northeast and throughout the entire country. Again, we see the looming impact of new technologies. The use of AI and other technologies in the automobile industry, including the advent of electric cars, is going to lead to even fewer workers being employed. And the question is what are the employers going to do? What is Washington going to do? These are not new issues for autoworkers, but against the backdrop of what I described earlier—the pro-union landscape right now—we are likely to see some major activity here.

Then there is the very current dispute between the Teamsters and UPS. As of July 25, it looks like a strike will be averted as the parties have reached a tentative agreement. If the deal is ratified, it will avoid what would have been the largest strike ever against one employer in the history of the United States, involving almost 340,000 workers. It will be interesting to see what happens here in the coming days, weeks, and months. If UPS accedes to key Teamster demands on compensation and protection for part time workers, this will mean a greater likelihood that we will see aggressive union organizing campaigns at their non-union competitors’ facilities.

So far we’ve been talking about the already-unionized, but what about union organizing? Are we seeing similar trends there?

Yes, unions have been able to organize in recent years in sectors we have never thought of before, like museums and nonprofits, and even retail, all areas where, in the past, unions have feared to tread. And then there are the high-profile companies that have seen organizing drives, like Trader Joe’s and Apple and Amazon. But we don’t know what the payoff is going to be for unions in this arena. There is a lot of activity, but often they haven’t ultimately been able to negotiate any collective bargaining agreements. Take Starbucks. More than 8,000 workers at more than 300 Starbucks stores voted to unionize. But so far, none have enacted a collective bargaining agreement. With Amazon, one major warehouse was organized, but the company refused to bargain because of what they allege to be irregularities in connection with the conduct of the election. So, we are not yet on the brink of any consummation of arrangements through which workers’ economic positions can be enhanced.

What might people who are pro-labor not be thinking about as they celebrate the renewed energy and power of unions?

If unions are reasonably successful in some of these negotiations and strikes, the employers that they’re dealing with are naturally faced with major competitive challenges coming from other employers that either don’t have unions at all or have weak unions. Take the UPS-Teamsters dispute. We don’t know yet if there will be a strike, as a tentative deal between the Teamsters and UPS was just struck this morning, but let’s assume UPS accedes to many or most of the union’s demands. Who is going to benefit? Yes, UPS workers benefit, but let’s not forget who else likely will: FedEx and Amazon. FedEx and Amazon are both non-union. FedEx has been successful thus far in getting the courts to characterize their drivers as independent contractors who have great difficulty, because of the way in which our laws operate, to even organize a union. Now they are conceivably going to have a strong competitive advantage against UPS, which has had to make concessions that are going to impact the company in many ways, not just financially. So to really win for workers, Sean O’Brien, head of the Teamsters, is going to have to organize Amazon. He’s going to have to organize Federal Express. Well, that’s formidable. If he’s able to organize the non-union or weak union competitors of employers like UPS, well, then we can say that they have made a lasting contribution to the way in which our society is working and have really promoted a more egalitarian society. But we are a long way from that.

William B. Gould IV is Charles A. Beardsley Professor of Law, Emeritus, at Stanford Law School. A prolific scholar of labor and discrimination law, Gould has been an influential voice in worker–management relations for more than 50 years and served as Chairman of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB, 1994–98) and subsequently Chairman of the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board (2014-2017). Professor Gould has been a member of the National Academy of Arbitrators since 1970. As NLRB Chairman, he played a critical role in bringing the 1994–95 baseball strike to its conclusion and has arbitrated and mediated more than 300 labor disputes, including the 1992 and 1993 salary disputes between the Major League Baseball Players Association and the Major League Baseball Player Relations Committee. His 11th and most recent book is For Labor to Build Upon: Wars, Depression and Pandemic (2022).

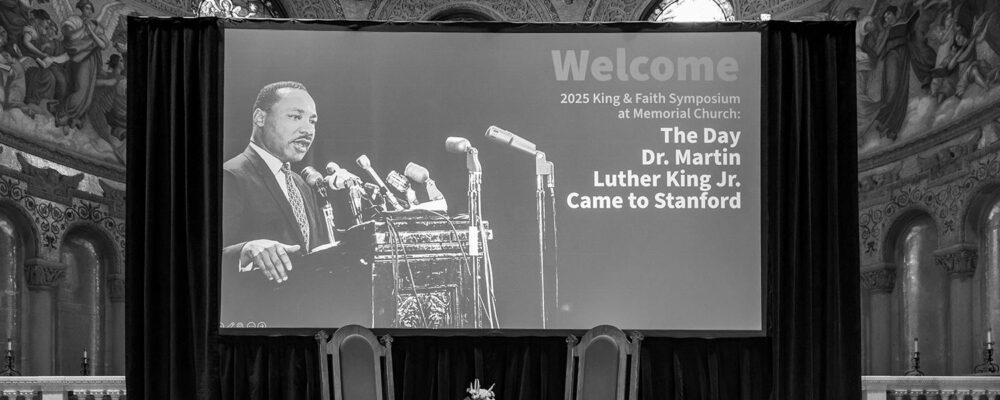

“Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies 8,180 acres, among the largest in the United States, and enrols over 17,000 students.”

Please visit the firm link to site