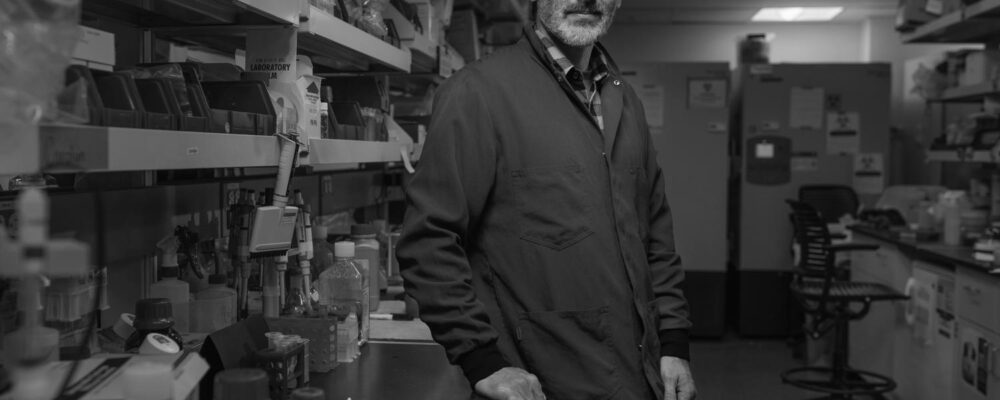

Before he became an expert on corporate leadership, Charles O’Reilly spent five years in the U.S. Army. There he witnessed the stark divide between good and bad leaders and realized how much influence they had on the people who worked for them.

Now a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, O’Reilly says his time in the military sparked his interest in leadership, particularly his fascination with the “narcissist” personality type. “If you think about Elizabeth Holmes at Theranos, if you think about Travis Kalanick at Uber, they are people who the press looked at and said, ‘They are transforming the world.’ But in fact, at the end of the day, they destroyed organizations and people’s lives.”

These narcissistic CEOs may be outliers, but their high-profile scandals demonstrate just how important an executive’s individual characteristics and values are. O’Reilly, along with Xubo Cao, a PhD student in organizational behavior at Stanford GSB, and Donald Sull, a senior lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management, explores this idea in a new paper that seeks to understand how the personality of a corporation’s leader influences its culture and performance.

“What we’re suggesting in this article is that skill sets and experience are important, but that it’s also probably worthwhile thinking about what the personality of the individual is,” O’Reilly says. “The intuition is that culture and strategy need to fit, and therefore personality needs to fit as well.”

O’Reilly and his coauthors used a natural language algorithm on earnings call data to assess the personalities of 460 CEOs at more than 300 companies. They then analyzed 1.2 million Glassdoor employee reviews to calculate the firms’ organizational cultures, including factors such as collaboration, execution, and performance. The results showed a significant correlation between a CEO’s personality and their firm’s culture.

Specifically, the paper looks at CEO personality through the lens of the Big Five model, which measures the essential traits of openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and neuroticism. It found a correlation between each Big Five trait and nine dimensions of organizational culture (as determined by Sull and colleagues in 2019). Extraverted or sociable CEOs were associated with agility, collaboration, and execution, while agreeable or trusting CEOs were associated with flexibility and internal focus. Highly conscientious or detail-oriented CEOs typically led companies whose cultures placed less value on agility, innovation, and — interestingly — execution and results.

Executive Functioning

A personality of a leader that might work in one situation might be exactly the wrong personality in another situation

Charles O’Reilly

Although the larger picture suggests that extraversion and agreeableness have the most positive effects on organizational culture, the perfect combination of CEO personality traits does not exist. Each of the nearly infinite combinations of the Big Five comes with trade-offs — boosting one trait consequently diminishes another. This means that the ideal personality of a CEO will largely depend on their company.

“A personality of a leader that might work in one situation might be exactly the wrong personality in another situation,” O’Reilly says. “Leaders who are very open-minded and creative can be great for companies whose strategy is to be innovative. They could be terrible in companies where the strategy is to be cost-conscious and incremental.” For instance, a trendy clothing company may benefit from having a leader high in openness and innovation, but a bank might be better off with someone who does things by the book.

This concept is consistent with the study’s findings, which showed distinct personality profiles across industries. CEOs in the finance and insurance sector tend to be less agreeable, altruistic, and compromising, while those in healthcare are the opposite. Manufacturing CEOs demonstrate higher levels of conscientiousness; tech execs have lower levels.

Previous studies have applied the Big Five to executives, but O’Reilly’s study uses a large, cross-organizational sample to look more deeply at how exactly a CEO imbues their personality into an entire company’s culture. The mechanism is relatively simple, O’Reilly explains: Essentially, executives model certain behaviors and encourage their employees to follow suit. He puts it this way: “If that’s what successful people do, then that’s what you’ll have to do if you want to be successful.”

Cao cites his own experience with his academic mentor as an example. “He solves problems in a very creative way. I try to emulate that,” he says. However, this can come with trade-offs: “Sometimes I get caught up in a novel, creative idea and forget to pay much attention to detail.”

Managing Corporate Culture

Whether a company capitalizes on the link between its culture and strategy can mean the difference between survival and collapse. In a companion paper, Cao, O’Reilly, and Sull observe meaningful relationships between CEO personality and innovation, finding that openness has the most significant, positive association with an innovation-oriented culture — an important feature of companies that can adapt in the face of change.

O’Reilly cites Blockbuster and Borders as two companies that failed because they lacked cultures of innovation. “If they had leaders that could adjust, they could have survived,” he says, referring to their inability to respond to changes in how people consume media. “Think about Walmart. Walmart is in healthcare now. They’re running healthcare through their stores. They have leaders who are able to play two games at the same time — to be good at selling lots of stuff in big stores while also experimenting.”

O’Reilly finds that corporate culture is not an abstract, random quality but a fully controllable asset. Whether CEOs utilize it to improve performance, efficiency, employee satisfaction, team dynamics, and longevity is another matter. In a survey of more than 1,300 executives, 92% answered that improving their firm’s culture would increase its value. So if CEOs are not oblivious to the power of corporate culture, why haven’t more prioritized it? The answer, O’Reilly says, is practical: They have more pressing matters to attend to.

“CEOs acknowledge that culture is important for the success of their company, but they have lots of what they think are more important things to do: They’ve got day-to-day business, they’ve got profits to worry about, they’ve got all sorts of things,” he says. “So even though CEOs are aware of culture, the vast majority of them are not particularly good at managing culture.”

“Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies 8,180 acres, among the largest in the United States, and enrols over 17,000 students.”

Please visit the firm link to site