Nearly half of all U.S. workers fail to use all their allotted vacation days, according to a recent survey from Pew Research Center. The reasons they cite include having too much to do, concern about falling behind at work, and a reluctance to ask coworkers to cover their responsibilities.

What’s more revealing to us is what they left unsaid — and often don’t recognize. None of us want to admit that we would rather feel overwhelmed than underwhelmed. Most of us prefer being too busy to not being busy enough. We often experience a greater sense of our own value when we’re working than we do when we’re not. Working is not just a way to stay busy, but also to prove our worthiness — to others and to ourselves.

Immersion in work helps hold off feelings of inadequacy, anxiety, loneliness, sadness, and emptiness that can arise when we have time off. We dread being bored. Even if we don’t particularly enjoy or feel passionate about the work we do, we often consider it less anxiety-producing than the alternatives. The result is that without the right guardrails in place, we silently collude with employers who encourage us to overwork.

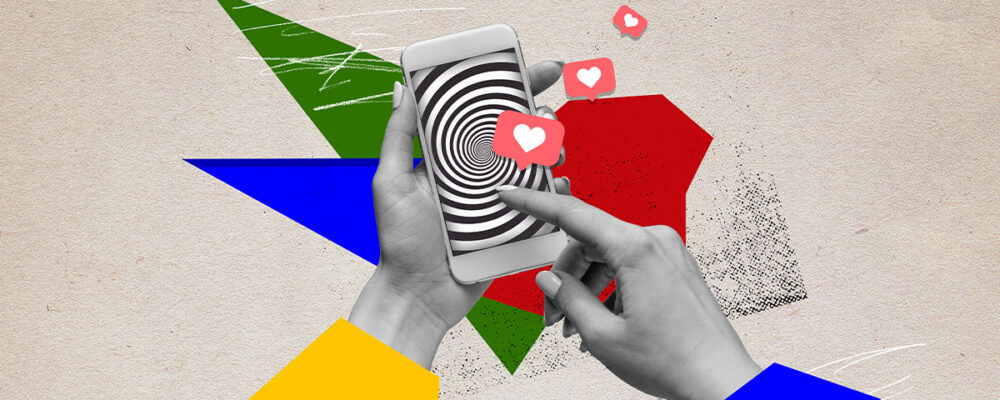

Workaholism, writes Bryan Robinson, a psychologist, and author of the book Chained to the Desk, is “a compulsive disorder that manifests itself through self-imposed demands, an inability to regulate work habits, and an over-indulgence in work — to the exclusion of most other life activities.” It’s called workaholism precisely because it is a form of self-anesthetizing. Whether the drug of choice is work, alcohol, drugs, the internet, video games, food, shopping, or countless other activities, the point is to escape from feelings we’re determined to avoid.

The irony is that putting in long and continuous hours and thinking constantly about work actually makes it harder to be fully absorbed and engaged in our jobs. Over time, it leads to diminishing productivity, higher rates of burnout, and even to increased likelihood of mortality. A 2021 World Health Organization study found that working 55 or more hours per week — compared to 35-40 hours — is associated with a 35% higher risk of a stroke and a 17% higher risk of dying from heart disease.

What sets workaholism apart from other forms of addiction — especially in a capitalist economy that reveres money above all else — is that it’s not only socially acceptable, but also materially and socially rewarded. Unless we’ve done the self-inquiry necessary to acknowledge and understand what’s driving our overwork, most of us continue to feed our addiction without even recognizing we have one.

Both of us — Eric and Tony — have struggled through our adult lives with the compulsion to work to the exclusion of other activities. For the first decade and a half of his career, Eric put in 12-hour days, plus a one-hour commute each way. After a series of personal challenges, he finally decided to see a therapist for the first time in his life. He also began a daily meditation practice and immersed himself in the literature around burnout.

In 2009, while working at Gap Inc, Eric helped to create an initiative to bring the practices he was learning to his company. The first move was something called the Results Only Work Environment, permitting corporate employees to work towards results rather than putting in a set number of hours. Eric is currently the Chief People Officer at Neiman Marcus, and the two of us have worked together on training leaders and employees alike to more skillfully manage their energy by getting more renewal, so that they are more sustainably and fully fueled.

But for all his conviction and commitment, Eric still finds it a constant challenge to resist the pressure to value work above all else in a corporate world that continues to overwhelmingly reward those who push themselves the hardest. That has been true everywhere he’s ever worked, and at nearly every company with whom Tony has worked.

Twenty years ago, Tony founded The Energy Project in order to make a science-based case to companies that intermittent rest and renewal not only results in better health and greater work satisfaction for their employees, but also to more sustainable high performance and productivity. In truth, he was also advocating for the very thing he needed to learn himself.

When it comes to overwork, Tony has generated myriad rationalizations for the hours he works: He loves what he does. It doesn’t feel like work. He gets great satisfaction from making a positive difference in people’s lives. Despite these noble-sounding explanations, work has been Tony’s “drug” of choice. It’s the most reliable way to feel a sense of his own worthiness — and to avoid difficult emotions.

At one point, partly as a lark, Tony decided to attend a Workaholics Anonymous meeting (and yes, they exist). There were four other people gathered around a basement table — a paltry turnout. As he was leaving, one of the participants turned to him. “Welcome to the French Resistance,” he said. “There are 5 million workaholics in New York, and you’ve just met the only four who are in recovery.”

So, what are the most effective ways to intervene if you find yourself compulsively overworking? Based on our experiences, we recommend trying these strategies:

Acknowledge the degree to which compulsively working is true for you.

You can’t change what you don’t notice. Ask yourself these questions: How clear and focused is your mind when you’ve been working long and continuous hours? How fatigued are you? What’s the impact on your mood? And what is the cost to others in your life? Be skeptical about the stories you tell yourself to rationalize your behavior.

Focus on two primary commitments: sleep and exercise.

This requires rhythmically expending and renewing energy. It’s critical to prioritize sleeping enough hours every night to feel fully rested, whatever that number means for you. For the vast majority of us, it’s at least seven hours. The second commitment is to get at least 20 to 30 minutes of brisk exercise during the day. We have both prioritized these two practices, and we’re convinced they’ve been key to avoiding our burnout, even though we still struggle to limit the hours we work.

Choose one activity in your life that gives you the purest enjoyment.

Make it something that gives you the most freedom from your work. For Tony, it’s ballroom dancing and tennis. For Eric, it’s meditation and working out. Whatever you decide to do, schedule it at designated times each week. Doing so dramatically increases the likelihood that you’ll make it happen.

Become more aware of what you’re feeling in your body, especially after you’re working for extended periods of time.

Humans are not designed to operate like computers, at high speeds, continuously, for long periods of time. We’re at our best when we work for no more than 90 minutes at a time and then take a rest. The body is the most reliable barometer of whether you need to renew and refuel, but all too often we ignore its signals, or override them.

Given how much overwork is rewarded in our culture, it’s reasonable to expect some anxiety to arise when you give yourself time to rest and renew. Rather than racing back to work, see if you can simply sit a little longer with those feelings. The more you can simply observe the part of you that’s anxious, the more you’ll discover it isn’t all of who you are. Your worst fears about not working won’t come true, and your capacity for non-doing will progressively grow. When it comes to combating burnout and mitigating workaholism, even a little self-care goes a long way.

“Harvard Business Review is a general management magazine published by Harvard Business Publishing, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Harvard University. HBR is published six times a year and is headquartered in Brighton, Massachusetts.”

Please visit the firm link to site