Small bio-integrated devices that can interact with and stimulate cells could have important therapeutic applications, including the delivery of targeted drug therapies and the acceleration of wound healing. However, such devices all need a power source to operate. To date, there has been no efficient means to provide power at the microscale level.

To address this, researchers from the University of Oxford’s Department of Chemistry have developed a miniature power source capable of altering the activity of cultured human nerve cells. Inspired by how electric eels generate electricity, the device uses internal ion gradients to generate energy.

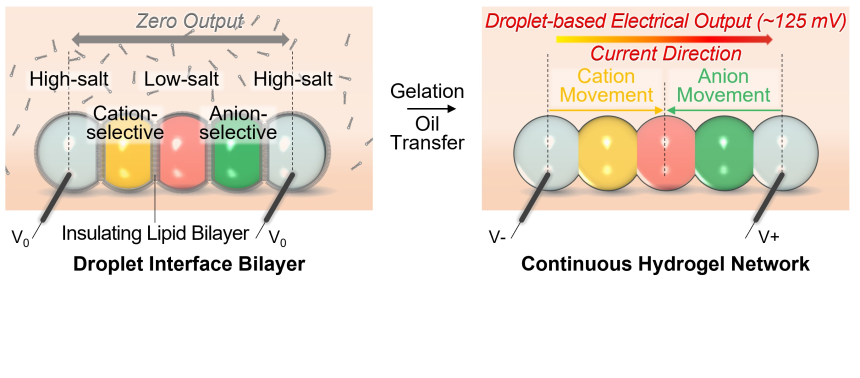

The miniaturized soft power source is produced by depositing a chain of five nanolitre-sized droplets of a conductive hydrogel (a 3D network of polymer chains containing a large quantity of absorbed water). Each droplet has a different composition so that a salt concentration gradient is created across the chain. The droplets are separated from their neighbours by lipid bilayers, which provide mechanical support while preventing ions from flowing between the droplets.

The power source is turned on by cooling the structure to 4°C and changing the surrounding medium: this disrupts the lipid bilayers and causes the droplets to form a continuous hydrogel. This allows the ions to move through the conductive hydrogel, from the high-salt droplets at the two ends to the low-salt droplet in the middle. By connecting the end droplets to electrodes, the energy released from the ion gradients is transformed into electricity, enabling the hydrogel structure to act as a power source for external components.

Image: Enlarged version of the droplet power source, for visualisation. 500 nL volume droplets were encapsulated in a flexible and compressible organogel. Image credit: Yujia Zhang.

In the study, the activated droplet power source produced a current which persisted for over 30 minutes. The maximum output power of a unit made of 50 nanolitre droplets was around 65 nanowatts (nW). The devices produced a similar amount of current after being stored for 36 hours.

The activation process for the hydrogel droplet power unit. Left, before the battery is activated, an insulating lipid prevents ion flux between the droplets. Right: The power source is activated by a thermal gelation process to rupture the lipid bilayers. Ions then move through the conductive hydrogel, from the high-salt droplets at the two ends to the middle low-salt droplet. Silver/silver chloride electrodes were used to measure electrical output. Image credit: Yujia Zhang.

The activation process for the hydrogel droplet power unit. Left, before the battery is activated, an insulating lipid prevents ion flux between the droplets. Right: The power source is activated by a thermal gelation process to rupture the lipid bilayers. Ions then move through the conductive hydrogel, from the high-salt droplets at the two ends to the middle low-salt droplet. Silver/silver chloride electrodes were used to measure electrical output. Image credit: Yujia Zhang.

The research team then demonstrated how living cells could be attached to the device so that their activity could be directly regulated by the ionic current. The team attached the device to droplets containing human neural progenitor cells, which had been stained with a fluorescent dye to indicate their activity. When the power source was turned on, time-lapse recording demonstrated waves of intercellular calcium signalling* in the neurons, induced by the local ionic current.

Dr Yujia Zhang (Department of Chemistry, University of Oxford), the lead researcher for the study, said: ‘I am very grateful for the immense support and abundant resources provided by the Bayley group and the Department of Chemistry, University of Oxford, which have allowed me to push the boundaries of what we thought was possible. Droplet 3D printers, microfluidic printers, and many other chemical biology techniques have enabled me to develop synthetic tissues with unique capabilities. We believe it will open the door towards interesting advancements for synthetic tissues.’

The miniaturized soft power source represents a breakthrough in bio-integrated devices. By harnessing ion gradients, we have developed a miniature, biocompatible system for regulating cells and tissues on the microscale, which opens up a wide range of potential applications in biology and medicine.

Dr Yujia Zhang (Department of Chemistry, University of Oxford)

According to the researchers, the device’s modular design would allow multiple units to be combined to increase the voltage and/or current generated. This could open the door to powering next-generation wearable devices, bio-hybrid interfaces, implants, synthetic tissues, and microrobots. By combining 20 five-droplet units in series, they were able to illuminate a light-emitting diode, which requires about 2 Volts. They envisage that automating the production of the devices, for instance by using a droplet printer, could produce droplet networks composed of thousands of power units.

Professor Hagan Bayley (Department of Chemistry, University of Oxford), the research group leader for the study, said: ‘This work addresses the important question of how stimulation produced by soft, biocompatible devices can be coupled with living cells. The potential impact on devices including bio-hybrid interfaces, implants, and microrobots is substantial.’

* Calcium signalling is a key mechanism through which neurons communicate with one another to coordinate biological activities such as neurotransmitter release, neuronal firing, synaptic plasticity, and gene transcription.

“The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world’s second-oldest university in continuous operation.”

Please visit the firm link to site