Over the last winter, the potential energy crisis and high uncertainty resulted in a GDP contraction of 0.9% over Q4 and Q1. This decline was clearly caused by external factors. In particular, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine massively disrupted gas and energy supply forcing a rapid reorganization. Fortunately, downside scenarios of energy rationing for the industry did not play out. While the risk of a renewed gas shortage in 2024 seems low, the German economy still suffers from several structural challenges. GDP growth stagnated in Q2. Leading indicators such as the ifo or PMIs clearly point to ongoing weakness in H2. As a result, we expect a GDP decline of 0.5% in 2023 (annual average), well below other G7 countries.

Germany among top 10, eight years in a row

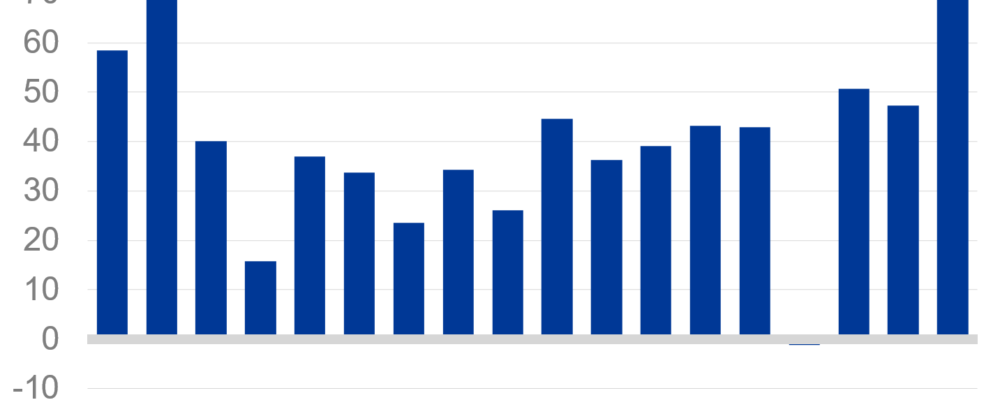

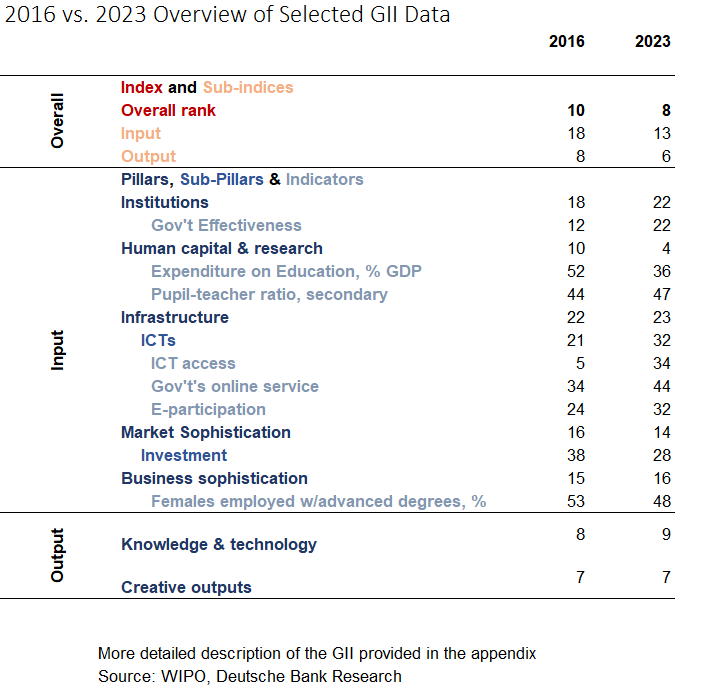

This week, the Global Innovation Index (GII) has been released for 2023. It is a key index for 132 countries, first published in 2007. It is composed of 5 input- and 2 output-related pillars. These in turn are fed with data from a total of 80 indicators, providing a detailed picture of competitiveness. Over the history of the GII, Germany has made strong progress in its overall capacity for innovation, reaching the top 10 for the first time in 2016. The good results were mainly driven by steadily rising scores in the areas of ‘human capital and research’ reaching 4th place in 2023. In addition, Germany improved in both output-related sub-pillars during the strong economic performance in the second half of the 2010s. It has even been able to catch up in the sub-pillar ‘Investment’ coming from 75th in 2019 to 28th in 2023. Despite these strengths and improvements, Germany lags behind in digitalization and labor supply.

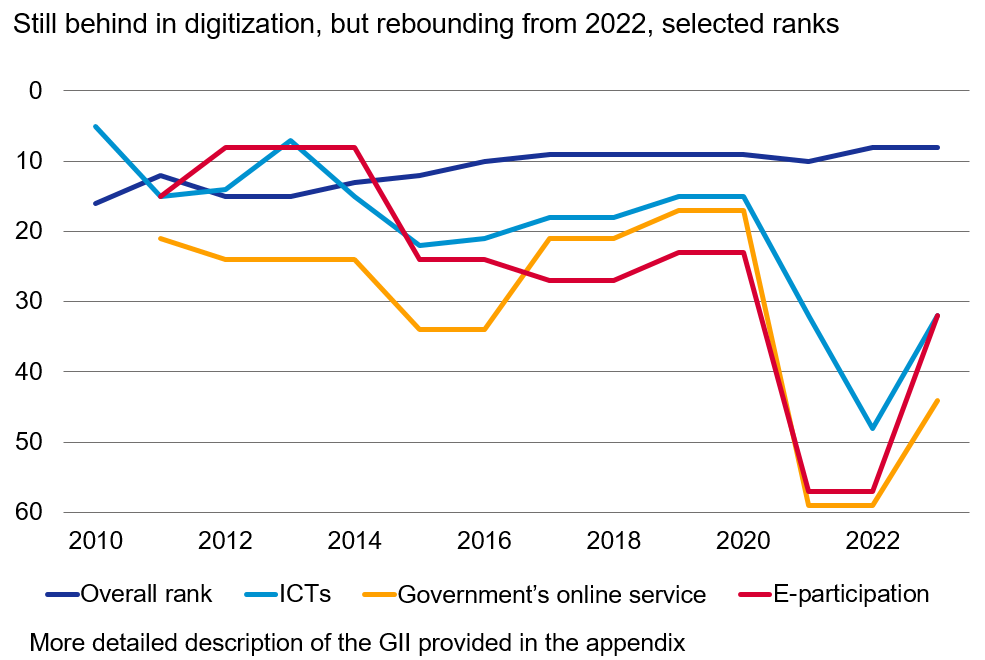

Digitalization: Still trailing the peer group but some important improvements

The performance in the sub-pillar ‘Information and communication technologies (ICTs)’ points downward. From 15th place in 2020, the country slipped to 48th place in 2022, followed by a rebound to 32nd place in 2023. However, the descent is still substantial. This is partly due to the decline in ‘ICT access’ where Germany ranked 7th in 2020 and dropped to 34th in 2023. The best performers in the sub-pillar are unsurprisingly Korea and Estonia. But the Netherlands and the UK are leading among Western European countries, ranked 7 and 8. Germany’s poor performance in digitalization is also reflected in ‘E-Participation’. Here, we lost touch with the top countries and fell as low as rank 57 in 2022, before recovering to 32nd in 2023. These declines also show up in other measures. For example, in 2022 the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) of the EU Commission sees Germany at rank 13 out of 27 with a lead of many western and northern countries, Germany’s traditional peer group. Particularly striking is that less than 50% of Germans claim to have basic digital skills (23rd place) or ‘Integration of digital technology’ where Germany ranks 16th.

Germany is also a laggard in digital public services. Here, DESI sees Germany also ranked below EU average. Likewise, the GII indicator ‘Government’s online service’ ranks us very low. It dropped from 34th rank in 2016 to 59th in 2022, followed by 44th in 2023. A vivid example of how to do better is Denmark with its digital identification NemID introduced in 2010. Today, 90% of the population uses this method for everything from applying for government benefits or renewing a prescription to opening a bank account. The low performance in the digital realm is likely to explain the overall decline in the sub-pillar ‘Government effectiveness’. There, Germany fell from 12th place in 2016 to 22nd in 2023. Interestingly, we lost seven spots from 2021 to 2022 alone. Presumably, other countries digitalized their public services during the pandemic whereas Germany slowed down due to red tape. The Onlinezugangsgesetz (Online Access Act) implemented in 2017 was not a success. It obliges all levels of the administration to digitalize their services by the end of 2022. Due to the iw Koeln[1], only 18% of all administrative processes were digitalized at the start of 2023 and many other countries in the EU fared much better. Consequently, Germany fell to rank 22 in ‘Government effectiveness’ in 2023. It is therefore also hardly surprising that, on the output side, the share of ICT services in the total trade volume is only at 2.1% (56th in GII) in 2023.

All of these GII rankings, both in the public sector and overall, show that Germany is clearly a laggard when it comes to digitalization. Citizens of the top digital countries can often rely on digital solutions that are not available in Germany. However, according to the GII, there have been some important improvements, suggesting that Germany is on the right track.

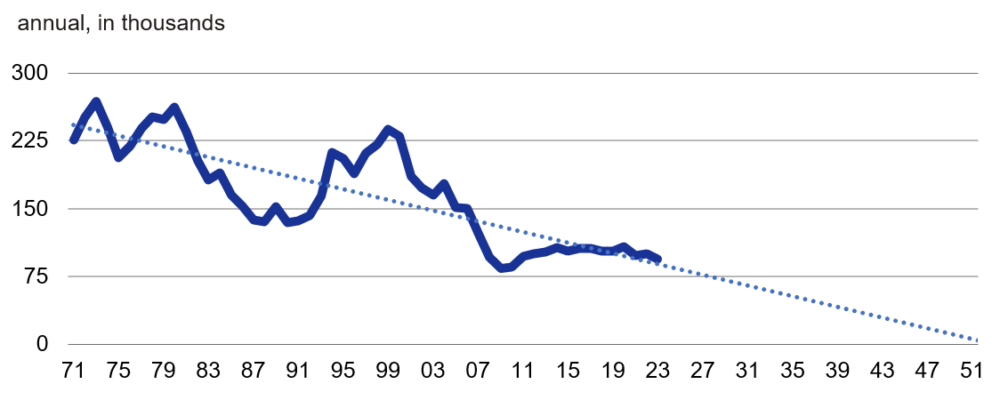

Demographics: Supply shortages in the labor market deteriorating

The second major challenge for Germany is demographics. The last year in which Germany had a net birth surplus was 1971[2]. The ratio of the over-65s to the 20-65s – dubbed the old-age dependency ratio – rose from 20%[3] in the 1970s to 32% in 2023. More than a quarter of Germany’s employees are older than 55 years. As many will retire over this decade, a further deterioration is virtually unavoidable. For certain types of skilled workers, the excess demand is already immense. For instance, 77% of companies report difficulties in recruiting IT staff[4]. Similarly, 30% of companies in the construction industry express a lack of workers despite a very severe recession. Shortages are also very common in the health and hospitality sector. Net migration of more than 300,000 people annually cushioned the scarcity. Still, it needs to be on the order of 500,000 people as well as rapid integration into the labor market to neutralize the demographic shift.

Despite these growing problems, Germany still refrains from important reforms. The GII shows that highly skilled women are too rarely integrated into the labor market. Since 2015, in the sub-pillar ‘Females employed with advanced degrees’, Germany ranks at 48 in 2023, at a similar level as in previous years, well behind countries from our peer group. That implies that Germany is missing out on urgently needed and already well integrated workers. Another negative for Germany is stagnant ‘labor productivity growth’, another GII sub-pillar. A boost in productivity could close part of the supply gap in the labor market, and again, digitalization can play a critical role. Here, it has fallen further and further behind, to as low as 98th place in 2023.

Several reforms are urgently needed

From 2015 to 2019, Germany’s GDP growth was 1.7% on an annual average, clearly above today’s potential. The underlying deterioration in some aspects of competitiveness was temporarily disguised by zero and negative interest rates. However, the recent interest rate normalization unveiled structural shortcomings. The German economy is now at a crossroads and must finally switch into a reform mode. First, the public sector needs to fully digitalize its processes. Second, the appropriate infrastructure and an increase in the digital literacy of the society must be achieved to give the companies the opportunity to excel and increase their productivity. This will also help to overcome the increasing lack of workers. Finally, the participation rate of women in the labor market needs to be increased. Tax reforms and the expansion of full-day care and education are essential to encourage more women to bring their much-needed skills to the workplace.

Despite the challenges, Germany was and is a pioneer in R&D, thanks to its excellent STEM professionals and their well-known products which are the backbone of our economy and society. In the past, the German economy has shown tremendous resilience in overcoming crises and reinventing itself. If the country succeeds again in these areas, it can remain among the top 10 countries with respect to innovation and competitiveness.

Appendix on the GII methodology

The GII is an annual ranking of 132 countries and their capacity for innovation. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), located in Geneva, publishes the GII since 2007 investigating a country’s capacity for innovation in an international comparison. The index was created by the then Dean of the Saïd Business School at Oxford University during his tenure at INSEAD in 2007. Since then, the Index has been accompanied by high-profile researchers. One of the current distinguished members of the Advisory Board is Monika Schnitzer, Professor of Economics at LMU Munich and member of the German Council of Economic Experts. In addition, the index is particularly broad, covering around 97% of global GDP in PPP terms.

[2] BiB – Pressemitteilungen – Trotz gestiegener Kinderzahl: Höchstes „Geburtendefizit“ seit Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs (bund.de)

[3] Bevölkerungspyramide: Altersstruktur Deutschlands von 1950 – 2060 (destatis.de)

[4] Erwerbstätigkeit – Statistisches Bundesamt (destatis.de)

Deutsche Bank AG

Please visit the firm link to site