California’s “Three Strikes and You’re Out” law, which passed in 1994, was one of the tough-on-crime measures that swept the country in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Later, as the prisons were overflowing, the stories started to come out: A man sent to prison for life for stealing a pair of shoes. Another sentenced to life for breaking into a soup kitchen.

Michael Romano, JD ’03, is the founder and director of the Three Strikes Project at Stanford Law School, the first law school program of its type in the country, focused on securing reduced sentences for incarcerated people deemed to be serving disproportionate sentences. He has guided hundreds of Stanford Law students through the process of winning the release of more than 200 Californians imprisoned under the state’s Three Strikes law. Romano and his students also helped change the law in California and he has been active in reforming the process of federal and state clemency.

On a recent edition of the Stanford Legal podcast, Romano sat down with co-hosts Richard Thompson Ford, the George E. Osborne Professor of Law, and Pamela Karlan, the Kenneth and Harle Montgomery professor of public interest law, to talk about his groundbreaking work. The following is an edited excerpt of the full interview, which can be found here:

Karlan: Can you explain what the three strikes law is, where it came from, and what its effects have been?

Thirty years ago there was a pair of horrific murders of young girls in California and, after struggling with deciding how to handle a violent crime, especially sensational and violent crime, sentiment spread throughout California and the country to enact laws that would send people to prison for the rest of their lives if they committed three felonies. Almost every state in the country passed some version of a three strikes law.

The way that it worked in California was particularly harsh because the felony threshold for crimes like simple drug possession and petty theft could be for extraordinarily minor crimes. As a result, we had thousands and thousands of people who were sentenced to life in prison for street crimes. Not that they were innocent, but they had committed these minor crimes—not the kind of crimes that prompted the law in the first place.

Karlan: How did the Three Strikes project get started and what is it designed to do?

I was clerking on the Ninth Circuit and there were two cases that came before the judge I was working for. One involved somebody who forged a DMV application. He filled out the DMV application for his uncle who didn’t speak English. Yes, that’s a felony. You’re not supposed to do that. But he received a life sentence under the Three Strikes Law for that. The other case involved aiding the sale of $5 worth of crack cocaine to an undercover police officer. Because of Andrade and Ewing (U.S. Supreme Court cases upholding sentences imposed under California’s three strikes law), if the judges spent 20 seconds on these cases, that was a lot. That shocked me. Were these really outlier cases or were there a lot of them? When I finished my clerkship, I started working for a criminal defense firm in San Francisco, and we had another one of these cases: three strikes for possession of 0.03 grams of methamphetamine. I was doing research and kind of pulling the thread, and it turned out there were not just a couple or a dozen or hundreds. There were thousands of people who are serving life sentences for these really minor crimes.

When I came to Stanford and the law school was expanding its clinical program, I went to Larry Marshall, who of course was legendary in the wrongful conviction world, and I said, “Larry, we should do sort of an Innocence Project here, but not “innocent.” It’s the Guilty Project.” These people are guilty. But the question was whether a life sentence was appropriate and could we figure out a legal strategy, especially after Ewing and Andrade, that might afford these people some relief.

Karlan: How did you get around the provision in three strikes law that judges had to sentence these people to life in prison, even if they didn’t think it was the appropriate punishment?

We decided to borrow from death penalty litigation. Around the same time, the Supreme Court recognized that there was a right to effective representation, not only at trial, but at sentencing. I thought that maybe we could apply the same principle in three strikes cases, because there is a narrow loophole that courts can use to avoid the three strikes sentencing in extraordinary circumstances. So we started filing habeas cases in California, based on this idea that our clients received ineffective assistance of counsel at the sentencing phase. An extraordinary mitigating circumstance which had never been presented before in court could be presented—similar evidence that you hear in death penalty cases: mental illness, low cognitive function, extraordinary amounts of childhood trauma and abuse. It was a bit of an experimental claim. This strategy had been the province of capital cases. We ended up winning some cases. In some ways we even surprised ourselves. One case led to another and we’ve been extraordinarily lucky and successful.

Karlan: So have all of these cases been cases where the claim is that the original lawyer should have brought this material out and didn’t, or are there other sorts of claims that you’re bringing as well?

We’re not devoted to any particular claim. Occasionally we’ll meet with clients and they’ll say, “I’m innocent,” and we generally don’t go down that road. There is new law in California on disproportionate punishment under the state constitution, which we have litigated. We recently won an equal protection claim. There have been a number of reforms to sentencing laws, which we’ve actually helped enact, that also raise new claims. There are new laws in California that allow law enforcement to nominate people for resentencing, and we’ve also successfully represented clients under those laws. We definitely started under this idea of ineffective assistance of counsel, and that’s still our kind of our bread and butter claim, but we usually raise two or three claims for each of our clients.

Ford: I understand you’re working on reintegration of people post-release. How is that work going and how challenging is that process of avoiding recidivism?

It’s an extremely heavy lift and it’s a good problem to have. So, we would win these cases, and we would meet people at prison gates and say, “Congratulations and we’re so happy for you. And where are you going next?” Of course we realized almost instantaneously that our clients had nowhere to go. The vast majority of people sentenced under the three strikes law are homeless and destitute and addicts and didn’t have intact families or communities to begin with.

We have formed partnerships with different residential treatment, housing, job training placement programs throughout California. We created the Ride Home Program, through which we’ve hired some of our former clients who are out and doing great, to go pick up people at the prison gates, bring them to their first meal, and then hand them off to their residential programs, usually in Los Angeles or in the Berkeley area.

Karlan: Recently, you had an interesting oped in the New York Times about clemency. Can you tell us a little bit about your ideas and where you think we’re headed?

We were asked to help on then-President Obama’s efforts to award clemency to people who are overly incarcerated and subject to racially disproportionate punishment in the federal system. It was extraordinarily flattering and exciting. It was also frustrating to see how difficult it was to actually navigate the clemency process and for people to actually trickle up or get distilled down to where the President would sign off on their release.

I sit on a committee to advise Governor Newsom here in California to avoid the sticky political problems that clemency raises. For example, can we identify people who are doing very well in prison and may have proven their rehabilitation, but instead of having the executives, who are very politically sensitive, sign off on these cases, can we instead just bring those cases back to court? And once in court, have an open discussion about what their rehabilitation has been like, whether or not they remain a threat to public safety, what was their original crime, and do they have a reentry plan. None of that conversation happens in the clemency process. In California, we have a process where the prison system can actually nominate people who’ve been incarcerated for long periods of time and send them back to court to have this conversation and maybe be resentenced. The federal system actually has a similar law but it is almost never used. And so my oped was about encouraging the Biden administration to do something similar.

Prison officials really have a good sense of who’s incarcerated, who’s unfairly there, who’s safe to be released, and they don’t feel really part of that process. They just feel like they’re in the warehousing business.

Ford: I want to ask you about the Three Strikes Project’s work to reform the Three Strikes law in California.

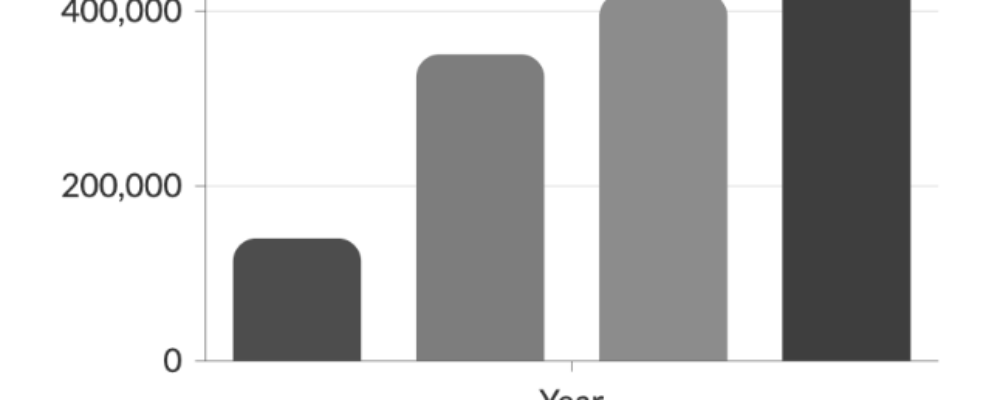

We were doing these individual cases in the basement of the law school when one day, our colleague, David Mills, knocked on my door and said, “This is great what you’re doing with these one-off cases, but aren’t there thousands of people?” We both essentially said, “There ought to be a law.” In California, if a law was passed by a voter initiative, as Three Strikes was in 1994, the only way it can really be reformed is by another voter initiative. That’s a huge campaign and a lot of money and a lot of mobilizing. Together with David and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, we built a campaign and students helped draft what would become the Three Strikes Reform Act of 2012, or Proposition 36, was put on the ballot in California and reformed California’s three strikes law to prohibit life sentences if the third strike is one of these non-serious, non violent sort of petty crimes, which did an extraordinary amount of good. Almost 4,000 people who had been serving life sentences were released under the measure. And of course it prohibited life sentences moving forward for these minor crimes.

I’m proud to be part of the work out here in California, and to some degree on a national level, to try to find solutions that actually reduce that harm and improve public safety at the same time. A lot of prejudices and bureaucracies and old ways of thinking remain, but we’ve been lucky for the most part and I’m optimistic that there will be further reforms.

Listen to the Stanford Legal Podcast

Michael Romano is the director and founder of the Three Strikes Project at Stanford Law School. Previously, he was founding director of the Stanford Criminal Defense Clinic. He currently teaches criminal justice policy and advanced criminal litigation and has published several scholarly and popular press articles on criminal law, sentencing policy, prisoner reentry and recidivism, and mental illness in the justice system. In 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom appointed Michael as inaugural chair of California’s criminal law and policy reform committee, the California Committee on the Revision of the Penal Code. He was principal author of the Three Strikes Reform Act (Proposition 36), one of the country’s first criminal justice reform initiatives, which led to the release of over 3,000 people serving life sentences for non-serious, non-violent crimes. He has gone on to develop and co-author numerous other reforms and led impact litigation, which together have resulted in reduced sentences for tens of thousands of additional people. Michael also founded the Ride Home prisoner reentry program, which has provided immediate assistance to formerly incarcerated people in 38 states and in 2015 partnered with the U.S. Dept. of Justice in support of President Obama’s executive clemency initiative. The work received numerous honors, including recognition by the White House as a “Champion of Change.”

“Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies 8,180 acres, among the largest in the United States, and enrols over 17,000 students.”

Please visit the firm link to site