Organizational structure can significantly influence the success of a token launch, and define how the project operates well into the future. There is no one-size-fits-all structure, so the process of choosing one must start several months ahead of a token launch. Even the most straightforward structure needs to be in place before launch to ensure compliance with any regulatory and tax obligations tied to issuing the initial token.

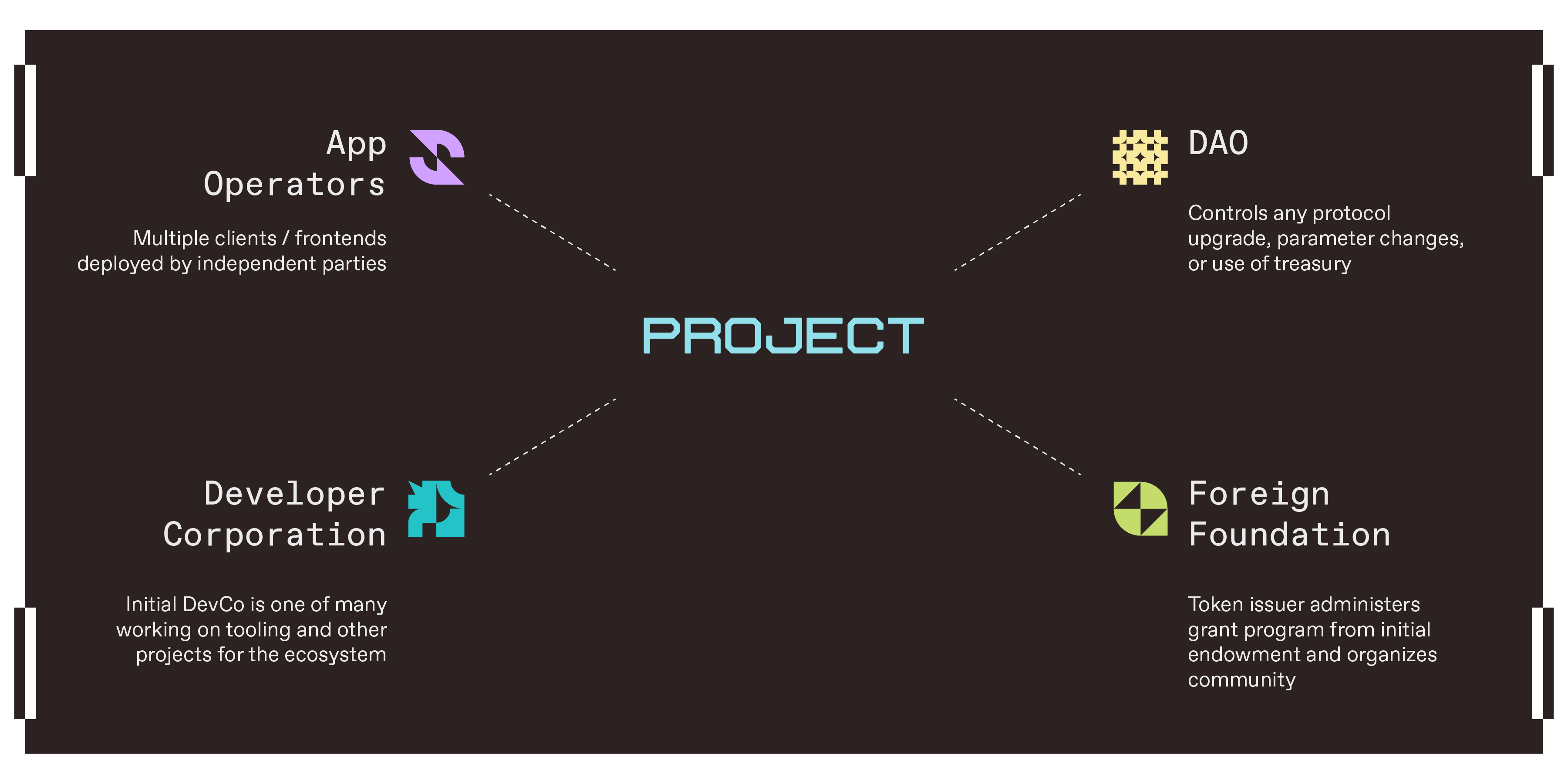

A typical structure for a web3 project includes the original developer corporation (also known as DevCo), a foreign foundation, a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), and third-party protocol or app developers.

Hundreds of decisions go into setting up even a simple organizational structure. Again, no two projects are alike, but here are some overarching principles projects should think through:

- DevCo/foundation split: At a high level, most projects should aim to make the DevCo one of many developers and app operators in the ecosystem, while the foundation coordinates community efforts and safeguards the credible neutrality of the project. The Ethereum ecosystem does a good job of separating the relative roles of DevCos and the Ethereum Foundation. Critically, a foundation should not exist in name only. It needs to have real substance and purpose. This could mean adding a founder to lead the foundation, or providing the foundation with marketing, communications, and go-to-market operations that are focused on bringing new developers into the ecosystem and helping organize the community.

- DAOs and eliminating token-based governance: While eliminating token-based governance has its merits, it’s difficult in practice. For instance, most projects will want to establish a treasury with governance tokens that haven’t been allocated in the initial distribution. While it is true that a foreign foundation could control the treasury, consolidating this power could raise centralization concerns. Alternatively, when tokenholders control the treasury, they decentralize economic power and determine whether the foundation should continue to receive funding.

- Third-party developers and applications: Attracting third-party developers to build on top of a project is one of the most difficult challenges when decentralizing. Developers generally choose projects based on a number of factors, including: (1) the tech underpinning a project, (2) the popularity of a project, (3) funding and incentivization, and (4) whether the project is credibly neutral public infrastructure, or a proprietary system that is controlled by a corporation (i.e., the difference between Ethereum and the Apple App Store). Critically, projects need to instill confidence in developers that they will be free to build a real business, and that the rules won’t be subject to arbitrary changes.

Two more organizational challenges to note, and emerging strategies for addressing them:

First, using a DAO adds a layer of complexity to a project’s operations. DAOs generally do not have legal existence, they can’t pay taxes, and they can potentially expose their members to unlimited liability, where they are liable for the project’s debts and tax compliance.

These risks are not theoretical, but new solutions may help. In March 2024 Wyoming passed a new legal entity form called a Decentralized Unincorporated Nonprofit Association (DUNA) – modeled on recommendations we helped make – which can solve all three problems for DAOs and afford them many additional benefits. Most importantly, the legal entity structure is permissionless and enables DAOs that use it to continue to function just like DAOs do currently. DUNAs are not suitable for all DAOs, so projects considering them should discuss with counsel.

Second, setting up a foundation that delivers meaningful value to the community is especially difficult if the foundation is located in a place that doesn’t have a strong web3 talent pool. To date, most projects have struggled with this problem as foundations are typically located in niche jurisdictions and hiring outside of those jurisdictions risks undermining the legal basis for these structures.

Some projects are now beginning to address this challenge by adding an operational subsidiary to their foreign foundation, typically located in a jurisdiction where it is easier to hire employees. The United Kingdom – with its strong talent pool, constructive approach to web3 regulation, and favorable tax treaties – is emerging as a strong candidate for this role. A foreign foundation’s operational subsidiary can be funded by the foundation and conduct all operations for the foundation, while reducing the risk of having employees located outside the foundation’s home jurisdiction.

Other projects are using independent U.S. foundations to supplement their foreign foundations. These U.S. foundations can initially be funded by the DevCo, and then receive ongoing funding grants from the DAO. Their operations can also include operating their own grant programs, providing development assistance, and coordinating decentralized governance. The Uniswap Foundation is a great example of this approach because it has effectively taken over stewardship of the Uniswap community and is now driving independent developer engagement and activity, thereby enhancing decentralization.

Ultimately, the organizational structure of a project will be determined by a number of factors: The project’s governance structure and economic model, any planned development work, the technologies underpinning any products and services, and the geographic location of the project and its target market. Be sure to work closely with counsel and tax advisors to implement an effective structure before launching a token.

“Andreessen Horowitz is a private American venture capital firm, founded in 2009 by Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz. The company is headquartered in Menlo Park, California. As of April 2023, Andreessen Horowitz ranks first on the list of venture capital firms by AUM.”

Please visit the firm link to site