2 May 2024

Some banks reduce balance sheet items around reporting dates. Such “window dressing” camouflages the true risks of a bank, impairs markets as well as bank resilience and supervision. The ECB Blog looks at how regulators and supervisors are taking action.

Banks commonly report and disclose financial information and regulatory metrics at the end of every quarter. In order to appear safer, and to face laxer regulatory requirements than they should, some banks shrink certain bank balance sheet items around reporting dates and expand them again right after. This practice, which has become known as “window dressing”, is unacceptable from a financial stability perspective as it undermines the objectives of bank regulation, risks disturbing the operations of financial markets and may lead to banks having insufficient resources in times of stress. Certain regulatory frameworks seem particularly vulnerable to window dressing, in particular those for global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) and for the leverage ratio.

Gaming the rules

The G-SIB framework imposes higher regulatory requirements on the world’s largest, most complex, interconnected and internationally active banks. It is based on an annual exercise that uses thirteen risk indicators to identify G-SIBs. These indicators are generally based on year-end data that are aggregated into a G-SIB score. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision expects that G-SIBs are subject to higher capital requirements, which increase with their calculated G‑SIB score. By reducing the underlying risk indicators at the end of a year, many banks can lower their overall capital requirements.

The leverage ratio framework aims to restrict the build-up of excessive leverage among banks by measuring banks’ capital in relation to their total exposures. Banks can therefore improve their leverage ratio by either increasing their capital or lowering their total exposures. Window dressers do the latter, but just at quarter-ends.

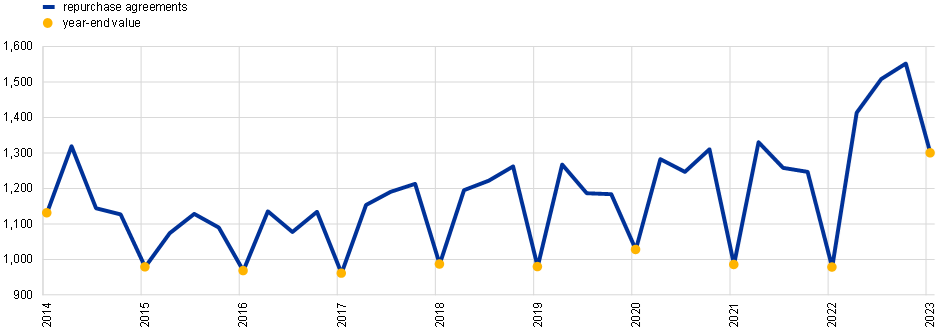

In both frameworks the volume of repurchase agreements (repos) is an important indicator for measuring risk and calibrating regulatory capital requirements. Repos are short-term secured loans traded between financial institutions on a daily basis. Their short maturities allow banks to actively reduce their volume around reporting dates. Chart 1 shows quarterly figures of repos for 23 European banking union (EBU) banks between 2014 and 2023. The year-end falls in repo volumes are clear, sometimes totalling more than 20% of the third quarter amounts.

Chart 1

Volumes of repos show strong declines at year-end for large European banking union (EBU) banks.

(quarterly data December 2014-December 2023, EUR billions)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations. Note: based on supervisory reporting from 23 banks.

While the observed year-end drops could be due to many factors, including a seasonal decline in the demand for banks’ market intermediation, many studies indicate that these patterns are substantially driven by active window dressing behaviour. The leverage ratio and G-SIB frameworks appear to provide the main incentives for window dressing, as for example discussed in a recent ECB Macroprudential Bulletin article and research by ECB staff.

Does it really matter?

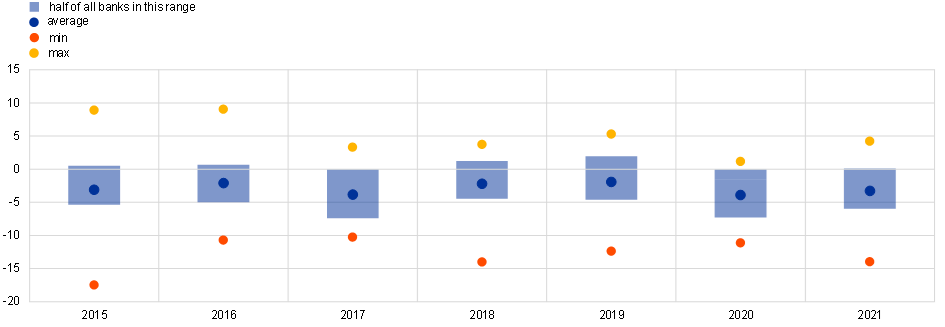

Yes, it matters! First, for accuracy: evidence shows that G-SIB scores based on year-end data may be up to 15% lower than scores calculated at other times of a year (Chart 2). Estimates also suggest that window dressing behaviour allowed up to 13 banks to reduce their capital requirements between 2014 and 2020, with three even managing to avoid being identified as G-SIBs entirely.

Second, for efficiency: the G-SIB framework is relative. That means that the systemic importance of a bank is measured in relation to that of other banks. Window dressing by some banks can therefore have negative effects on others. Specifically, banks that window dress would wrongly benefit from lower capital requirements while banks that do not could receive too high capital surcharges given their actual risk level.

Chart 2

Annual G-SIB scores can deviate substantially from estimated G-SIB scores based on quarterly data

Estimated G-SIB score declines at year-end

(percentages)

Source: ECB and ECB calculations Notes: The chart shows the range of estimated deviations of official G-SIB scores from estimated annual scores based on quarterly data for 23 large banks in the European Banking Union. The boxes cover the range of deviations that represent the middle 50% of all banks.

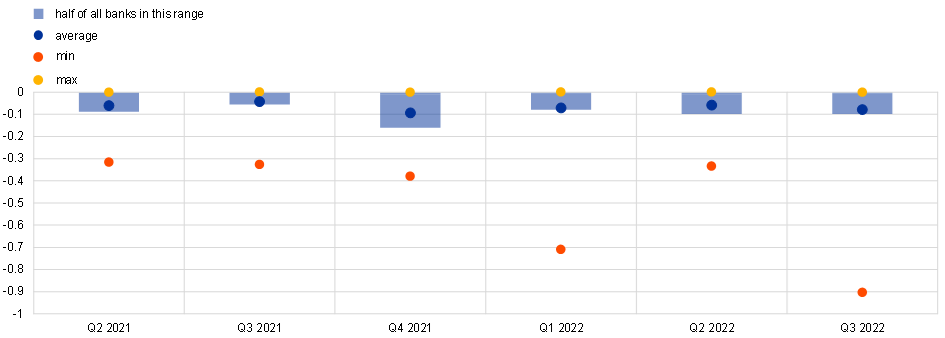

The leverage ratio framework reveals a similar story. Chart 3 shows that the reductions in the leverage ratio at quarter-end relative to the average over the quarter can be substantial in several cases: by around 0.3 to 0.4 percentage points and in one case even by 0.9 percentage points. For comparison, the minimum regulatory requirement for banks is to maintain a leverage ratio of 3 percent.

Chart 3

Strong reduction of leverage ratios at reporting dates

Reduction of leverage ratio at quarter-end

(percentage points)

Source: ECB and ECB calculations Notes: The reductions are calculated as the difference between the reported leverage ratio, which uses quarter-end values, and the leverage ratio calculated with average values over the quarter.

Curbing window dressing

In the past the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has explained why window dressing is unacceptable, because it undermines the intended policy objectives of both the G-SIB framework and the leverage ratio framework and risks disrupting the operations of financial markets.[1] Regulators and supervisors have always worked to contain the extent to which banks engage in window dressing, and this current response seeks to finally close the blinds on the practice.

Action has already been taken on the leverage ratio framework. EU legislators enhanced leverage ratio reporting and disclosure requirements in response to recommendations by the Basel Committee. Large banks must report and disclose both quarterly averages and daily amounts of securities financing transactions, which include repos. In December 2023 ECB Banking Supervision imposed leverage ratio capital add-ons for several banks, partly because they reported strong variability in the leverage ratio around reporting dates.[2]

Action is now being taken on the G-SIB framework as well. In March 2024 the Basel Committee started a public consultation to enhance reporting requirements for banks. The main proposal is that, at year-end, banks should report high-frequency (i.e. daily) averages for the most important balance sheet items that are relevant for the G-SIB assessment. Averages have the general advantage of smoothing out strong variations in the data over the year, and may therefore provide a more representative measure of underlying bank risk than a single observation at the end of the year. More representative data reporting by banks that participate in the G-SIB assessment exercise would not only ensure risk-commensurate capital requirements for individual banks, but it would also address the potential misallocation of capital across banks that results from the relative nature of the framework.

The views expressed in each blog entry are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem.

Check out The ECB Blog and subscribe for future posts.

“The European Central Bank is the prime component of the Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks as well as one of seven institutions of the European Union. It is one of the world’s most important central banks.”

Please visit the firm link to site