Previous studies in both humans and animal models have shown that the offspring of mothers living with obesity have a higher risk of developing obesity and type 2 diabetes themselves when they grow up. While this relationship is likely to be the result of a complex relationship between genetics and environment, emerging evidence has implicated that maternal obesity in pregnancy can disrupt the baby’s hypothalamus—the region of the brain responsible for controlling food intake and energy regulation.

In animal models, offspring exposed to overnutrition during key periods of development eat more when they grow up, but little is known about the molecular mechanisms that lead to these changes in eating behavior.

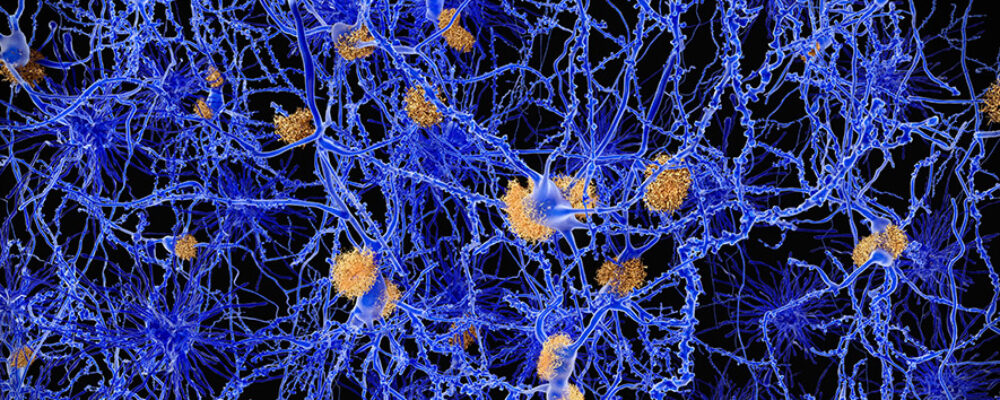

In a study published today in PLOS Biology, researchers from the Institute of Metabolic Science and the MRC Metabolic Diseases Unit at the University of Cambridge found that mice born from obese mothers had higher levels of the microRNA miR-505-5p in their hypothalamus—from as early as the fetal stage into adulthood. The offspring of obese mothers chose to eat more specifically of foods that were high in fat, which is consistent with fat sensing being disrupted in the hypothalamus.

Dr Laura Dearden from the Institute of Metabolic Science, the study’s first author, said: “Our results show that obesity during pregnancy causes changes to the baby’s brain that makes them eat more high fat food in adulthood and more likely to develop obesity.”

Senior author Professor Susan Ozanne from the MRC Metabolic Diseases Unit and Institute of Metabolic Science said: “Importantly, we showed that moderate exercise, without weight loss, during pregnancies complicated by obesity prevented the changes to the baby’s brain.”

Cell culture experiments showed that miR-505-5p levels can be influenced by exposing hypothalamic neurons to long-chain fatty acids and insulin, which are both high in pregnancies complicated by obesity. The researchers identified miR-505-5p as a regulator of pathways involved in fatty acid uptake and metabolism – high levels of the miRNA make the offspring brain unable to sense when they are eating high fat foods. Several of the genes that miR-505-5p regulates are associated with high body mass index in human genetic studies, showing these same changes in humans can cause obesity.

The study is one of the first to demonstrate the molecular mechanisms linking nutritional exposure in utero to eating behavior.

Dr Dearden added: “While our work was only carried out in mice, it may help us understand why the children of mothers living with obesity are more likely to become obese themselves, with early life exposures, genetics and current environment all being contributing factors.”

Reference

Dearden, L et al. Maternal obesity increases hypothalamic miR-505-5p expression in mouse offspring leading to altered fatty acid sensing and increased intake of high-fat food. PLOS Biology; 4 Jun 2024; DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002641

Adapted from a press release by PLOS Biology

“The University of Cambridge is a public collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the third-oldest university in continuous operation.”

Please visit the firm link to site