One of the ongoing discussions about the establishment of a digital euro – a central bank digital currency currently being scoped by the European Central Bank

– is about the holding limit. This limit, which would determine the maximum value of digital euros a consumer would be allowed to have, is currently proposed to be between €3000 and €4000.

The ECB also proposes to link holdings of digital euros automatically to a user’s bank account – a so-called ‘waterfall’ approach. If a user does not have enough digital euros for a payment, the amount of digital euros will be topped up directly from the linked bank account. This would ensure smooth and efficient payments, but it also sets up an apparent clash of objectives.

The ECB has argued that part of the justification for establishing the digital euro is to provide a monetary anchor to an increasingly digitalised economy, like the role cash plays today. For this to apply, consumers must hold sufficient digital euros.

But the ECB has also argued that the digital euro will provide a modern, widely accepted and European-based payment system. The waterfall approach and the link it establishes with a bank account reduces the need to replenish a stock of digital euros as these euros are used. Because of the convenience of automatic top-ups from a bank account, a consumer will have little incentive to hold large sums of digital euros, if any. If that is the case, why would a consumer open a digital-euro account? Consequently, the digital euro may not provide the monetary anchor it is meant to.

How to decide the holding limit

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) as an opportunity to reform the financial system

The argument in favour of either higher or possibly unlimited holdings of CBDCs, based on the idea that they may offer an opportunity to transform the financial system, has been made by a number of authors. For example, if the digital euro were to be remunerated (ie digital euro holdings would earn interest, which is currently not planned), it could enable a better transmission of monetary policy (Claeys and Demertzis, 2019). Similarly, CBDCs are more efficient in providing liquidity than deposits (Niepelt, 2024).

Minimise the disruption to the financial system

Despite the possible benefits described above, central banks have not said they want to transform the financial system by establishing CBDCs. Central banks have different reasons for putting in place digital currencies (see Demertzis and Martin, 2023), but all agree that in doing so they would aim to minimise the disturbance caused to the financial system. This is also true for the ECB (Panetta, 2022).

The rationale for putting a cap on CBDC holdings is to ensure that the migration of funds from retail banks accounts to CBDC accounts does not reduce the amount of private deposits in ways that would have a material economic impact on financial intermediation. But as Table 1 shows, the numbers that central banks have arrived at differ significantly. For the digital euro, Bidder et al (2024) suggested a different holding limit to the ECB, arguing that an amount between €1,500 and €2,000 would guarantee financial stability and increase welfare.

All central banks ask what the maximum value of holdings should be if CBDCs, if taken up in full, are not to disturb financial intermediation. Bindseil (2020) explained the ECB thinking on the digital euro holding limit. Should every individual transfer this maximum amount from their retail account to their digital euro account, it would imply a 15 percent reduction in aggregate retail deposits for each bank. This would represent around €1 trillion, which is also the value of the banknotes currently in circulation. Furthermore, from a consumer’s perspective, €3000 is the average net monthly income of euro-area households.

The Bank of England meanwhile is considering a much higher limit of between £10,000 and £20,000 (Cunliffe, 2023) for each citizen. The reasoning behind this higher limit is similar to that given by the ECB: proper risk management together with usability of the currency. Nevertheless, there would be no hard restriction on the limit, meaning it could be modified after the introduction of the digital pound. For corporate digital pound accounts, a limit has not yet been established, though it would be higher than that set for individuals, given companies’ greater liquidity needs (Bank of England and HM Treasury, 2023).

In a similar vein, Li et al (2023) showed that a limit of 25,000 Canadian dollars (about €17,000) would also be effective in avoiding financial system disruption. Again, they put forward the need to maintain the benefits provided by private financial intermediaries and therefore aim to avoid excessive shifts from private deposits to digital currency holdings.

Finally, the Chinese central bank is already offering a digital renminbi to the citizens. Unlike the uniform setup the ECB is currently considering, the digital renminbi has different alternatives – ‘wallets’ – consumers can choose from. Holding limits vary depending on the level of identification, with higher holdings allowed for lower levels of anonymity.

How much digital cash is needed?

The question on holdings limits is generally asked from the point of view of the maximum amount that can be held without disturbing the financial system. It should be asked also what the minimum amount should be for the digital euro to be the financial anchor in an increasingly digitalised payment system.

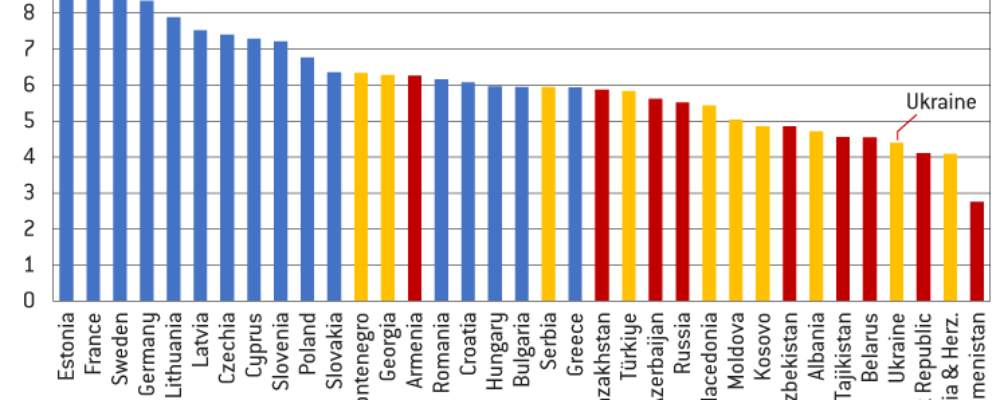

As the digital euro is meant to be a substitute for cash (except it will not be completely anonymous), we look at the amount of cash per capita in circulation as a proxy for the cash demand. Figure 1 shows how much cash is held at the beginning of the day by consumers in euro-area countries. There is a range, from a high of €121 in Austria to a low of €46 in the Netherlands.

Figure 1: Average cash amount in the wallet at the beginning of the day, by country

Source: ECB, SPACE report 2022.

If the digital euro were used similarly to physical cash, numbers in Figure 1 would suggest that the currently proposed holding limit of €3000 to €4000 limit is very generous, and a much lower limit could suffice.

But the proposed waterfall approach complicates the issue of the minimum amount of digital euros that should be held

. As well as automatic taking funds from a linked account in case of insufficient funds in the digital euro account for a transaction, the reverse will also apply: namely if a digital-euro account receives funds above the holding limits, the excess will be transferred into the linked account (the ‘reverse waterfall’ approach). This, no doubt, adds to the convenience of using digital euros, as one can always spend them without having to worry whether there are sufficient funds.

But this also means that consumers will never have to actively transfer money to their digital euro accounts. The consumer could, conceivably have zero digital euros in a digital euro account and still be able to use that form of payment. A zero amount, though, means there are no funds that are fully guaranteed by the central bank. Given that the consumer can use the digital euro for payments this way, why would they opt to hold more than zero digital euros at any given point? Doesn’t that then mean that the ability of the digital euro to provide an anchor to a digitalised system is compromised?

Conclusions

Retail banks worry that the €3000 to €4000 digital euro holding limit will lead to removal of a substantial proportion of funds at their disposal, meaning they can no longer be intermediated. Assuming there is significant public uptake of the digital euro, banks will therefore have less funds on which to make profits. If the digital euro were to mimic the way that cash operates, then compared to the cash that is held today, the holding limit may be too large.

On the other hand, the waterfall approach, which no doubt adds to the convenience of payments, also removes any incentive to hold digital euros at all. Why then would a consumer open a digital euro account? The ECB will have to persuade the public how the digital euro will be a good digital equivalent of the current anchor to the system, cash.

References

Bank of England and HM Treasury (2023) The digital pound: a new form of money for households and businesses? Consultation paper, February, available at https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/paper/2023/the-digital-pound-consultation-working-paper.pdf

Bidder, R., T. P. Jackson and M. Rottner (2024) ‘CBDC and banks: Disintermediating fast and slow’, Discussion Paper 15/2024, Deutsche Bundesbank, available at https://www.bundesbank.de/resource/blob/931090/be2be8b2c5324245e4147d6306689312/mL/2024-04-29-dkp-15-data.pdf

Bindseil, U. (2020) ‘Tiered CBDC and the financial system’, Working Paper Series No 2351, European Central Bank, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2351~c8c18bbd60.en.pdf

Claeys, G. and M. Demertzis (2019) ‘The next generation of digital currencies: in search of stability’, Policy Contribution 2019/15, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/next-generation-digital-currencies-search-stability

Cunliffe, J. (2023) ‘The digital pound’, speech given at UK Finance, 7 February, available at https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2023/february/jon-cunliffe-speech-at-uk-finance-update-on-central-bank-digital-currency

European Commission, (2023) ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the establishment of the digital euro’, COM(2023) 369 final, available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52023PC0369

Li, J., A. Usher and Y. Zhu (2024) ‘Central Bank Digital Currency and Banking Choices’, Staff Working Paper No. 2024-4, Bank of Canada, available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2024/02/staff-working-paper-2024-4/

Niepelt, D. (2024) ‘Money and Banking with Reserves and CBDC’, The Journal of Finance, available at https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13357

Panetta, F. (2022) ‘The digital euro and the evolution of the financial system’, introductory statement at the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs of the European Parliament, 15 June, available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2022/html/ecb.sp220615~0b859eb8bc.en.html

Established in 2005, it is independent and non-doctrinal. Bruegel’s mission is to improve the quality of economic policy with open and fact-based research, analysis and debate. We are committed to impartiality, openness and excellence. Bruegel’s membership includes EU Member State governments, international corporations and institutions.

Please visit the firm link to site