In October 2023, the European Commission launched an ex officio (i.e. started by the Commission on its own initiative rather than at the request of industry) investigation into a sample group of Chinese manufacturers of electric vehicles (of the more than 300 that exist in total) and non-Chinese ones based in China. Manufacturers that agreed to participate in the investigation but were not included in the sample group could face countervailing import duties not exceeding the weighted average tariffs imposed on those manufacturers that were investigated.

This investigation falls under EU anti-subsidy regulations and complies with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. This means the tariffs are not intended to make imported products less competitive than their domestic counterparts but merely to offset the unjustified competitive advantage third-country subsidies bestow on exporters. The Commission calculates that advantage in the course of the investigation.

The Commission has gathered sufficient evidence that the manufacturers in question have received significant subsidies from the Government of the People’s Republic of China in various forms:

- direct transfers of funds

- tax credits

- public supplies of goods and services at below-market prices

- subsidies, export loans and credits, and lines of credit provided by state-owned banks as well as bonds underwritten by state-owned and privately owned banks at preferential terms

- export insurance at preferential terms

- reductions and exemptions on income tax, dividends and VAT

As well as proving that these subsidies exist, the Commission must also demonstrate a threat of injury to EU manufacturers and a causal link between the subsidies and the injury.

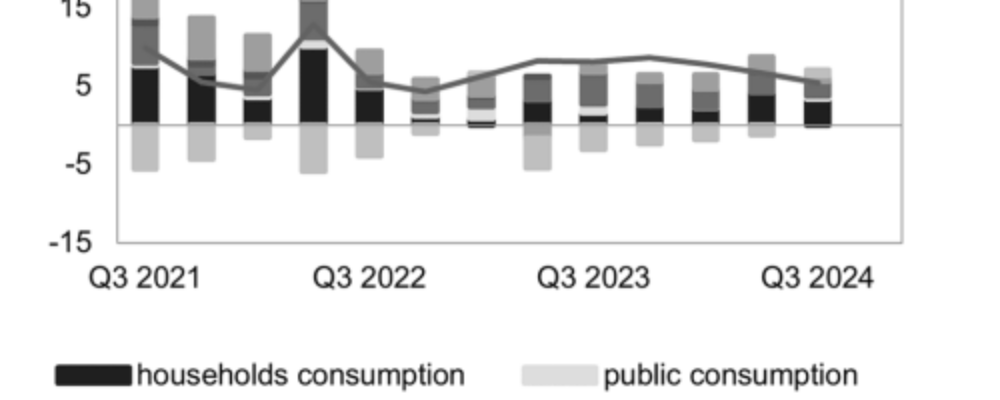

It has successfully proved that subsidised imports have grown at a sustained pace in both absolute and market share terms and that surplus capacity in China that cannot be absorbed by other markets is highly likely to result in a substantial increase in imports into the EU in the near future. European imports of Chinese electric vehicles have increased rapidly, rising from $1.6 billion in 2020 to $11.5 billion in 2023. By lowering production costs and selling prices, the subsidy policy puts pressure on European manufacturers’ sales, market shares and profits in the single market. As well as extensive subsidies, Chinese manufacturers also benefit from cheaper labour and energy. Fierce competition in the saturated Chinese market has led to a price war. Manufacturers are therefore seeking to make up for their squeezed margins in the Chinese market by selling their products at higher prices in the European market.

On 4 July, the Commission imposed provisional import duties, on top of the standard 10% import tariffs already in force, on three Chinese manufacturers: 17.4% for BYD, 19.9% for Geely and 37.6% for SAIC.

All other Chinese (or China-based) manufacturers that cooperated with the investigation but were not individually investigated are subject to a countervailing duty of 20.8%. BMW Brilliance Automotive, Audi FAW NEV Company, FAW-Volkswagen and Dongfeng Peugeot-Citroën all belong to this group. So does Tesla for the time being, though the latter could, following a substantiated request, receive “an individually calculated duty rate at the definitive stage”. Manufacturers deemed not to have cooperated face a 37.6% duty.

These provisional duties apply for four months – long enough to give Member States time to agree to the permanent tariffs proposed by the Commission (or to oppose them by a qualified majority vote – i.e. one backed by 15 countries and 65% of the EU’s population). The permanent tariffs, once agreed, will remain in force for five years.

What impact might these import tariffs have on Chinese exports and European prices?

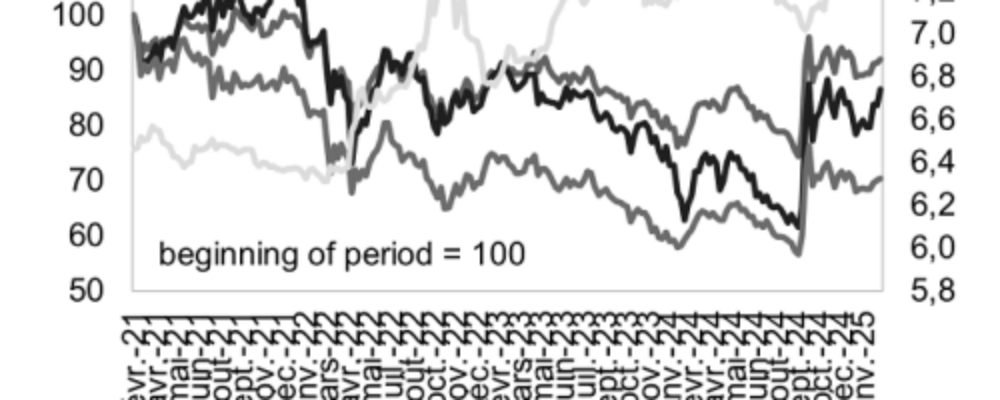

The Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW Kiel) expects the tariffs to have a limited impact on prices within the domestic market but a major impact on sales of Chinese electric vehicles in the single market. Simulations on five major European economies (France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Austria) using the KITE1 model show that an additional 21% tariff on electric vehicles imported from China would push selling prices up by between 0.3% and 0.9% in the long term and by nearly twice as much as that in the short term. The assumption is that Chinese manufacturers would absorb a big chunk of the import tariffs by cutting their margins. The premium available to Chinese manufacturers in the European market is so high that they still have room to lower their pre-tariff prices. However, the premium is not so high for non-Chinese manufacturers based in China and exporting to Europe, who do not receive the same level of subsidies as their Chinese counterparts. This could call into question China’s role as a base for exports to Europe for these manufacturers (be they European, Japanese or American). Weak growth and low profitability in their domestic market, a lack of attractive alternative export markets, and excess capacity – both existing and under construction – mean Chinese manufacturers are still very keen on the single market. However, the tariffs are likely to have a significant impact on the volume of electric vehicles imported from China, with the decline quantified at 42%. Even European manufacturers – who, through joint ventures, make 55% of electric vehicles produced in China and imported into the EU – would be adversely affected, though the impact on European added value would be limited, since 85% of the subcontractors they use are Chinese.

This decline in sales of Chinese vehicles would be offset by increased imports from other countries (+0.8%) and, above all, higher domestic production in Europe. Among the third countries that stand to benefit from the diversion of export flows, the big winners would be Japan, the United States and Turkey.

How might China respond?

China should use the next few months to negotiate lower tariffs in exchange for direct investment in the EU. BYD is set to open a production facility in Hungary, but the diversionary effect of tariffs will also benefit Turkey, which is also on course to host a production site for the Chinese manufacturer.

Negotiation implies the threat of reprisals. A non-escalatory approach would mean targeting products that are significant for European exports but not critical. Products that are central to China’s own interests would also be excluded. The aim would be to target countries that have significant leverage over European decisions (i.e. major influential countries) and/or to activate central political groups. This is how to understand the Chinese government’s decision to launch an anti-dumping investigation into European pork exports, targeting the core electorate of the European People’s Party and of a number of major exporting countries such as Germany, Spain and France. Although EU pork exports to China have already declined significantly over the past few years, they still added up to €3 billion in 2023 and could be hit hard by a hike in import tariffs. IfW Kiel estimates that an increase in Chinese import tariffs to 50% could lead to an 80% fall in German and Spanish exports of pork to China and a 55% fall in French exports. The threat of an investigation into cognac also targets France in particular, which has strongly backed the EU’s action on electric vehicles.

Other reprisals, some of which have already been applied in the past, remain a possibility, such as revoking licences to operate in China, encouraging Chinese consumers to boycott European products and imposing export controls. Having recently restricted exports of gallium, germanium and graphite, China could potentially target lithium, cobalt and copper, restrictions on which would pose a significant risk to the EU’s ability to manufacture green technologies.

However, China’s most likely course of action is to exert its influence on various EU Member States with the aim of sowing division and opposition to the European Commission’s actions.

How might the EU respond?

The EU has some other aces up its sleeve. The single market ban on products linked to forced labour or representing a risk to cybersecurity (because they incorporate cameras and sensors controlled by Chinese manufacturers) could be applied to cars. The Commission could also launch an anti-dumping investigation, particularly if Chinese manufacturers were to respond by lowering their prices. European countries could also draw inspiration from the example of France, which has made its “green bonus”, available to buyers of new vehicles, contingent on sustainability criteria, automatically excluding Chinese manufacturers. Other products where government subsidies distort competition could be targeted. Ideal candidates would be wind turbines, heat pumps, medical devices and steel.

The EU could also block Chinese companies from bidding on public tenders in the single market on grounds of unfair competition. Greater use could be made of other measures, such as controls on inward investment.

The EU’s most difficult task will be maintaining its members’ unity around these policies. Germany and Sweden have already signalled their opposition to countervailing duties on electric vehicles, while central European countries are more divided: they are integrated into the German value chain but could also benefit from Chinese investment. The Nordic countries have expressed fears over the risk that imports of raw materials needed by their burgeoning green industries might be blocked. France, meanwhile, has adopted a more aggressive stance on using tools to defend the single market and European industry.

A setback for China and a test of European unity

For China, the goal is to ensure that the European market remains open to its exports and to limit its trade confrontation to the United States. But there’s no denying that this procedure looks to be a setback. China is going to have to avoid any escalatory action that might prompt Europe to align its trade and security policies more closely with those of the United States and that could fuel the EU’s desire to further reduce the risk arising from dependence on China. However, this procedure could become an asset for the Chinese authorities if they were to succeed in making it an example of a new bilateral negotiation process. Meanwhile, European authorities have signalled both firmness and moderation by opting for an anti-subsidy procedure rather than an anti-dumping procedure that would have entailed higher tariffs. This procedure falls within WTO rules and aims to correct imbalances and competitive distortion. It has, however, been adopted as part of a preventive and protective approach before damage to the single market and European industry materialises.

The overriding priority for the European Union is to maintain its economic openness based on international rules, but this means managing a complicated trade-off between a market for affordable green technology and the development of a new European green industry. Although the EU is on its way to becoming the world’s second-largest market for electric vehicles, this transformation is happening at a time when China’s share of global demand is growing. Member States have differing views on these trade-offs depending on where they stand in relation to these technologies (whether they are manufacturers or consumers; how invested they are in old technology) and what kind of relationship they have with China. Will they be able to show a united front?

“Crédit Agricole Group, sometimes called La banque verte due to its historical ties to farming, is a French international banking group and the world’s largest cooperative financial institution. It is France’s second-largest bank, after BNP Paribas, as well as the third largest in Europe and tenth largest in the world.”

Please visit the firm link to site