These measures come on top of a long list of tariff and non-tariff barriers imposed since the trade war broke out between the two countries in 2018. The Peterson Institute for International Economics, a research organisation, estimates that 66% of Chinese exports to the US were already subject to customs duties averaging 19.3% before these latest announcements. The signing of the Phase 1 agreement and the election of Joe Biden did nothing to smooth the waters; indeed, condemnation of China’s trade practices is one of the few areas of bipartisan agreement in the US.

Unsurprisingly, with the US presidential election just six months away, the products affected are among the most emblematic of China’s output of manufactured goods: solar panels, electric vehicles, batteries and semiconductors as well as steel and aluminium, on which the Trump administration had already imposed import tariffs. Although the US trade deficit with China has fallen since 2018 – as has China’s share of total US imports, down from 19% in 2018 to 14.8% in 2023 – it was still high in 2023 at around $280 billion. Above all, it seems those countries that have benefited from the reconfiguration of supply chains, chief among them Mexico – which, since 2023, has regained its place as America’s biggest trading partner – and Vietnam, are also serving as intermediary platforms that help Chinese products circumvent import tariffs and restrictions, rather than genuine loci of production.

Aware of this circumvention, US authorities have so far not taken any particular steps to ascertain just how much Chinese added value is transiting through third countries. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, between Canada, the US and Mexico) is due to be renegotiated next year and this could pave the way for more checks, especially if Donald Trump wins the presidential election.

The new import tariffs apply to products and sectors targeted by the Inflation Reduction Act, where US authorities are pursuing a strategy of reindustrialisation, starting with the entire electric vehicle industry (from critical minerals through to finished vehicles and batteries), which has been the main focus of media attention over the past few months.

Electric vehicle tariffs: mostly window dressing

While the increase in import tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles is the most impressive measure, it is primarily a defensive move: Chinese inputs account for scarcely 2% of total US electric vehicle imports. US authorities, which are still struggling to bring inflation to heel, have been careful to ensure that higher import tariffs – usually passed straight on to end consumers – will not lead to a fresh upturn in consumer prices.

For example, the measures concerning minerals exclude those of which is China is a critical and essential supplier. Meanwhile, China’s solar panel industry is so price-competitive that higher import tariffs are unlikely to stop Chinese products being cheaper than their American and European counterparts.

However, if the European Union were to apply a similar tariff to electric vehicles, this would hit China much harder: in 2023, the European market accounted for nearly 40% of Chinese electric vehicle exports. Images of thousands of cars at the Port of Antwerp-Bruges highlight the scale of the offensive by Chinese manufacturers, for whom the European market has become a vital outlet for selling off surplus production and rebuilding their margins and cash positions, severely eroded by the price war that has been raging between manufacturers over the last few months.

While Xi Jinping repeated during his visit to France that “there is no such thing as China’s overcapacity problem”, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen took a harder line, saying the European Union could not accept “unfair trade” resulting from huge subsidies and would “not hesitate to make firm decisions” to “protect its economy and security”.

The conclusions of the report commissioned by the European Commission on subsidies in China’s automotive sector are due to be unveiled on 5 June and could result in higher import tariffs as early as July. With sales of electric vehicles already slowing in both China and the European Union, that would be a significant setback for Chinese manufacturers. Ursula von der Leyen did, however, say European tariffs would probably be “more targeted” than those imposed by the United States. If the increases were of the order of those that usually follow this type of investigation, import tariffs would rise from 10% to 20% – enough to hurt but not completely wipe out the price-competitiveness of Chinese vehicles.

China hit back by announcing that it had launched an anti-dumping probe, first into wine-based spirits like cognac – mainly targeting France – but also into polyoxymethylene copolymer, an engineering plastic used in phones, vehicle parts and medical equipment. China also opened the door to potential tariffs on agricultural products, including in particular dairy products subsidised under the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), even though it does not produce enough food to feed itself and remains heavily reliant on imports in this sector.

How might China retaliate?

Although China’s minister of commerce has announced that China “opposes the unilateral imposition of tariffs which violate World Trade Organization rules” and “will take all necessary actions to protect its legitimate rights”, in reality it has less room for manoeuvre than this rhetoric suggests. In 2018-2019, China retaliated by imposing higher import tariffs on US products, starting with energy commodities (oil, propane) and food commodities (soya, cotton, fruit and vegetables, etc.). Fifty-eight percent of US products are already subject to tariffs averaging 21.1%.

The remaining products are mainly high value-added industrial goods (aircraft, machine tools, semiconductors) of which there are sometimes few substitute suppliers. Even though inflation is much less of an issue in China than the rest of the world (China’s problem is more how to escape deflation), hiking import tariffs on these highly specific products could cause difficulties for parts of China’s production industry.

Another potential option would be to reimpose and tighten restrictions on exports of metals and rare earths, on which the US remains reliant. These measures were mainly aimed at countering multiple bans imposed by the US to prevent patents and technologies linked to the semiconductor sector being transferred to China and enabling the country to catch up in this area.

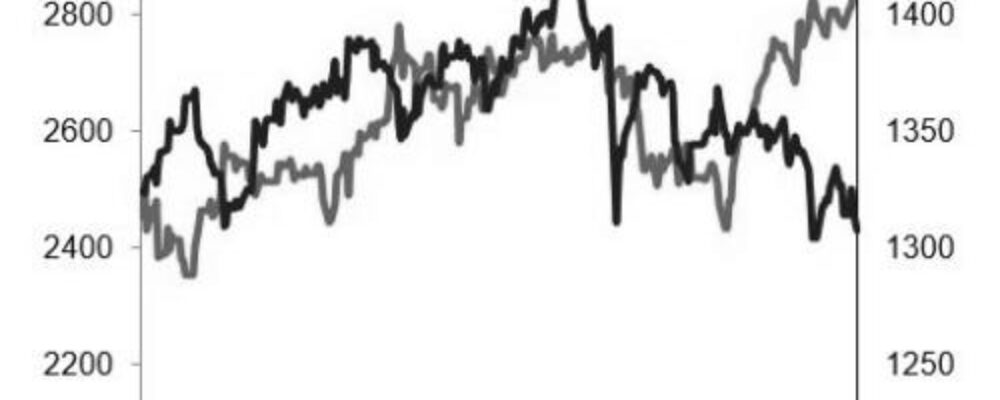

Lastly, China could manipulate its exchange rate to boost its competitiveness and offset price rises resulting from import tariffs. However, this option appears to lack plausibility. While China’s central bank has allowed the yuan to depreciate against the dollar over the past few months, which has also helped support exports, it seems unlikely that it would take deliberate action to further weaken its currency, especially in an interest rate environment that is highly unfavourable for China. Yuan depreciation could also trigger fresh capital outflows.

In the US, taking a firm stand against China has become an election issue. By announcing his intention to increase tariffs on all Chinese imports to 60% if he were to win the election, Donald Trump forced Joe Biden to clarify his position on the issue and take further action. While the measures announced by Biden have been carefully targeted so as to (i) maintain continuity with previous measures, (ii) target sectors already covered by the Inflation Reduction Act and (iii) limit, as far as possible, the impact on inflation for US consumers, most importantly they pave the way for Europe to take a firmer stand. With the conclusions of multiple investigations into Chinese subsidies in various sectors (wind power, solar panels, electric vehicles) not expected for several months, the EU could decide to increase import tariffs in the next few weeks.

In the mid-1980s, when the US trade deficit with Japan was at an all-time high, the US succeeded in forcing Japan to allow the yen to appreciate (the Plaza Accord of 1985) and Japanese car manufacturing sites to relocate to the US. The issues surrounding China are similar but the context has changed, with a purely economic rationale eclipsed by geopolitical issues of a more global nature. Joe Biden is also showing his environmentally friendly credentials by saying he wants the US to be able to control the chain of production linked to the climate transition. But if Donald Trump were to return to power, this could herald a renewed and more violent trade war and a return to basic protectionism with little regard for climate issues.

“Crédit Agricole Group, sometimes called La banque verte due to its historical ties to farming, is a French international banking group and the world’s largest cooperative financial institution. It is France’s second-largest bank, after BNP Paribas, as well as the third largest in Europe and tenth largest in the world.”

Please visit the firm link to site