31 July 2024

Central banks choose their words very carefully. And rightly so – policy makers’ wording can move markets and, eventually, the economy. This ECB Blog post shows how unexpected changes in communication influence growth and inflation.

Central banks need to communicate clearly. This helps the public understand the rationale behind monetary policy decisions and shape market expectations. Their statements sometimes provide explicit forward guidance on the future direction of monetary policy. These statements also reveal how decision-makers assess the economy, which in turn influences public expectations of how the central banks may react in the future. Can central bankers’ choice of words – the communication tone – influence the economy? In this blog, we show that the tone of ECB monetary policy communication indeed affects macroeconomic outcomes in the euro area.

Measuring the tone of communication

Our analysis is based on a central bank communication measure described in an earlier post. A natural language processing algorithm quantifies the tone of the Governing Council’s policy communication, specifically the ECB’s monetary policy statements (MPS) and press conference transcripts, which include journalists’ questions and the President’s answers. These texts are broken down into individual messages on specific topics, to which we assign numerical scores measuring their tone.

The algorithm is based on a set of dictionaries. First, the individual messages communicated during the press conference are categorised by topic distinguishing between monetary policy, the economic outlook, and inflation. Next, these messages are quantified both in terms of the direction and strength of the sentiment of the communication. For instance, the phrase “most measures of underlying inflation declined further” scores -1 (dovish), whereas a wording like “underlying inflation has fallen rapidly” would produce a score of -1.5 (even more dovish), with the index ranging from -2 to +2.

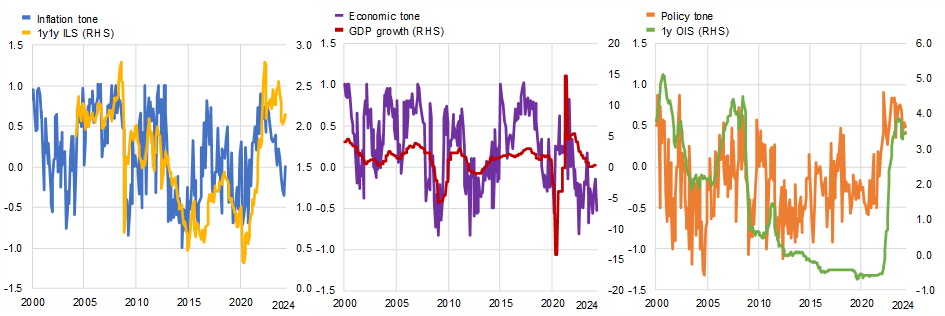

The resulting sentiment scores co-move closely with “hard” measures of related macroeconomic and financial variables (Chart 1). Changes in the inflation tone tend to lead changes in the 1y1y ILS forward rates – a common indicator for inflation expectations. Similarly, changes in the economic tone tend to lead GDP growth, suggesting that the sentiment contained in the ECB’s official communication is more than just a reflection of realised data. In addition, the tone of communication on monetary policy co-moves closely with market-based monetary policy expectations, as expressed in the 1y OIS rate. The exceptions here are during periods when the central bank applies forward guidance, as was the case for the ECB between July 2013 and mid-2022.

Chart 1

Co-movement of sentiment scores on inflation, the economy and monetary policy with macroeconomic data

(left hand scale in all panels: index; right hand scale in left and right panels: percentage points, right hand scale in middle panel: quarter on quarter percent change)

Sources: Refinitiv, Eurostat, and ECB calculations. Latest observations are 3 May 2024 for the 1-year ILS, 30 March 2024 for HDP and 11 April 2024 for the inflation and economic tone indices.

Notes: The charts show the evolution of the inflation, economic and monetary policy tone from the press conference transcripts following monetary policy decisions by the Governing Council (left hand axis) against the 1-year inflation linked swap (ILS) rate 1-year from now, the quarter-on-quarter GDP growth rate and the 1-year overnight indexed swap (OIS) rate (right hand scales).

However, we cannot simply relate changes in the sentiment scores to future economic outcomes: causality can run in both directions. Changes in policy sentiment are affected by the Governing Council’s monetary policy decisions which are influenced by the economic outlook in the first place.

The monetary policy sentiment index measures the tone of central bank communication on monetary policy, with an increase in the index signalling a more “hawkish” tone and a decrease in the index signalling a more “dovish” tone. That causality can run both ways is also true here: We know that central bank communication typically follows economic data. Therefore, changes in the monetary policy tone could simply reflect a shift in communication caused by changes in economic conditions. In such a case, the updated communication should not come as a surprise to the public and should have little effect on the economic decisions taken by households and firms.

Identifying unexpected changes to communication

But the tone of communication can also offer new insights into the direction of monetary policy itself. What happens when changes in communication on monetary policy come as a surprise to the public? To answer this question, we construct a measure of the extent to which central bank communication contains surprises, i.e. changes in the policy tone that are independent of both current and expected macroeconomic conditions.

We use two steps to isolate what we call “monetary policy communication shocks” from the monetary policy communication tone that the public expects. The first step is to measure the extent to which changes in the monetary policy tone are driven by changes in the Eurosystem’s inflation and growth projections that were available at a given Governing Council meeting. We also check if changes in the output and inflation sentiment indices discussed above matter. What’s left over are changes in the monetary policy communication tone that are plausibly independent of the revelation of the Governing Council’s information about the economic outlook and inflation. One could think of nuances in the Governing Council’s interpretation of data, or of situations in which the Governing Council draws different policy conclusions from the data than the average observer.

Even these residual changes in the monetary policy tone may, however, already be anticipated by the public. This can happen, for example, if Governing Council members express their opinions on monetary policy in public between policy meetings, or if the public already internalises how the ECB adapts its language to data releases. The second step is, therefore, to restrict the communication surprises to those in which the financial market reaction shows a pattern that is in line with a monetary policy shock, as outlined in the work of Jarociński and Karadi (2020). For instance, a hawkish shift in the policy tone would need to coincide with a drop in stock prices to be classified as a hawkish policy communication shock. A dovish shift in communication would need to occur alongside a rise in stock prices to count as a dovish policy communication shock. For the intraday financial market reaction to Governing Council meetings, we use the database of Altavilla et al. (2019).

How communication shocks affect the economy

Having identified these monetary policy communication shocks, we then estimate their dynamic effects on output and prices using the local projection method (Jordà, 2005). We control for macroeconomic and financial variables and estimate the model for both standard monetary policy shocks as typically identified in the literature and policy communication shocks. Standard monetary policy shocks reflect any surprise in the actual decision on interest rates, rather than unexpected changes in the surrounding communication. For instance, if the Governing Council were to raise rates by 25 bps and the public expected only 10 bps, that would spell a standard interest rate shock of 15bps. We estimate the model on a monthly frequency for the period from January 2002 to February 2020. For the latest data points, we allow the forward horizons to capture the evolution of the dependent variable up to January 2024.

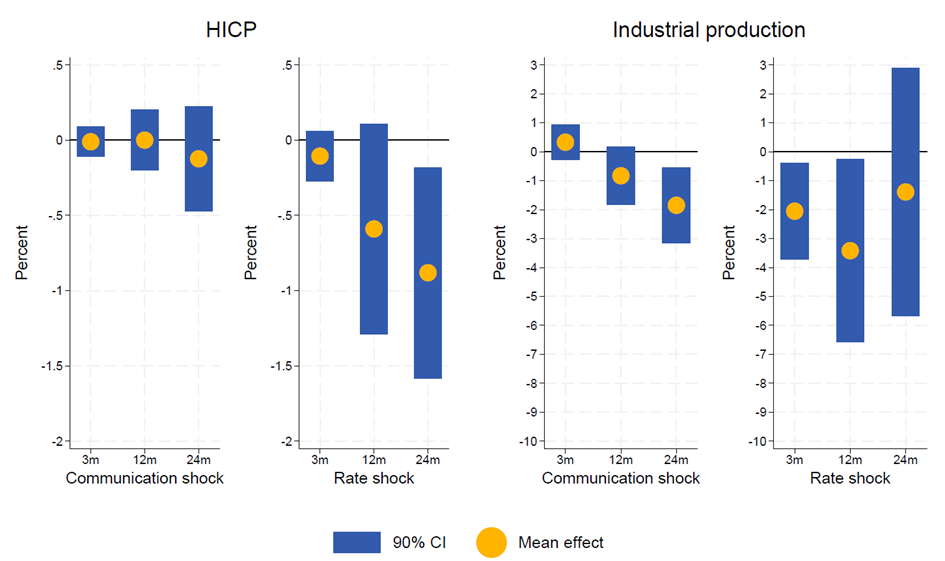

The results indicate that surprises in central bank communication significantly affect prices and real activity. A surprise hawkish shift in monetary policy communication (positive shock) leads to a significant and sizable decrease in inflation and economic activity. Chart 2 shows how output and prices respond to surprise changes in monetary policy-related communication and interest rates. The shocks are scaled to make “large” changes in communication and interest rates comparable, and we show the impact of the respective shocks on output and prices at different horizons.

We confirm the standard result that interest rates shocks have large impacts on the economy. In addition, we find that communications shocks matter too. Their effect is smaller, but still significant. Also, the main impact on the economy is reached later for communication shocks. For instance, we see real economic activity, measured as industrial production, decline by 2.3% two years after a hawkish communication shock. That effect compares to a decline of approximately 3.5% for an interest rate shock which is already playing out one year later. On inflation, a hawkish communication shock is associated with a 0.1 percent decline after two years; that compares to an almost 0.9 percent decline for an interest rate shock.

One reason for the delayed effects of communication shocks could be that observers need more time to internalise changes in central bank communication on monetary policy and to factor them into economic decision making. Changes in interest rates are directly observable and differences from market expectations are clear. A related question is whether communication shocks lead to changes in policy rates in the future. It turns out that futures markets for interest rates have a relatively muted response to our communication shocks, meaning that these shocks do not necessarily give a clear signal as to the future direction of policy rates.

Chart 2

Response of key macroeconomic variables to policy rate and communication shocks

(percentage change of output and inflation in response to tightening policy rate and communication shocks over the period Jan 2002 to Jan 2020).

Sources: Eurostat and ECB staff calculations. Regression sample: Jan 2002 to Feb 2020. Latest observation for the dependent variable taken up in forward regressions is Jan 2024.

Notes: Charts show the responses of industrial production and the HICP to both tightening policy rate and communication shocks, estimated using local projections (LP). The controls include: one lag of the respective response variable, the euro area unemployment rate, the ECB’s Composite Indicator of Systemic Stress (CISS) in financial markets, the commodity price index (all in log-levels), as well as the level of the economic outlook, inflation and monetary policy topic tone indicators, the 3-month OIS rate, a 10-year GDP-weighted synthetic sovereign bond yield, and the USD/EUR exchange rate. In each model, we control for the interest rate and communication shocks, respectively, as well as the “central bank information shocks” derived by Jarociński and Karadi (2020). All controls, except the response variables, enter the model contemporaneously. Finally, we add forward dummies (that enter at the t+h horizon) for the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. The pandemic period is defined as lasting from March 2020 to December 2021 while the war period is from March 2022 onwards. The policy rate shock, as well as the responses, are standardised such that a tightening communication shock results in a 25 bps increase in the 3-month overnight indexed swap (OIS) at peak. The units of the response variables are percentage changes. The communication shock is scaled such that it matches the size of the maximum absolute communication shock observed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The maximum surprise change in the topic tone indicator was observed for the March 2022 meeting, where the continuation/acceleration of the APP rundown announcement possibly triggered a large hawkish surprise in communication.

Our finding that communication shocks are affecting macroeconomic outcomes imply that central banks need to communicate clearly and carefully weigh their messages to minimise the risk of unintended surprises. Since our results confirm that central bank communication can be a potent policy tool, it should be used in a measured way to avoid ad-hoc surprises.

The views expressed in each blog entry are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem.

Check out The ECB Blog and subscribe for future posts.

“The European Central Bank is the prime component of the Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks as well as one of seven institutions of the European Union. It is one of the world’s most important central banks.”

Please visit the firm link to site