Nick Purser/Ikon Images

Recent pushback against diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives has caused many leaders to focus on the broader topic of allyship. These leaders want to be better allies and encourage their teams to do the same. In politically charged environments, however, leaders may find the mountain of advice on how to be an effective ally conflicting, confusing, polarizing, or overwhelming to apply. Without a clear decision-making framework, leaders may follow advice that feels right to them in the moment rather than intentionally applying the allyship interventions that would be most effective for their organization’s goals.

Leaders value a diverse workforce because research shows that diversity supports higher employee engagement, employee retention, and stock performance. However, top-down DEI initiatives often lead to pushback. What is missing in many companies is a participatory, empowering, and interpersonal approach to nurturing diversity, inclusion, and belonging through allyship.

But which allyship behaviors and priorities will work best for your organization?

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

A Three-Part Framework for Allyship

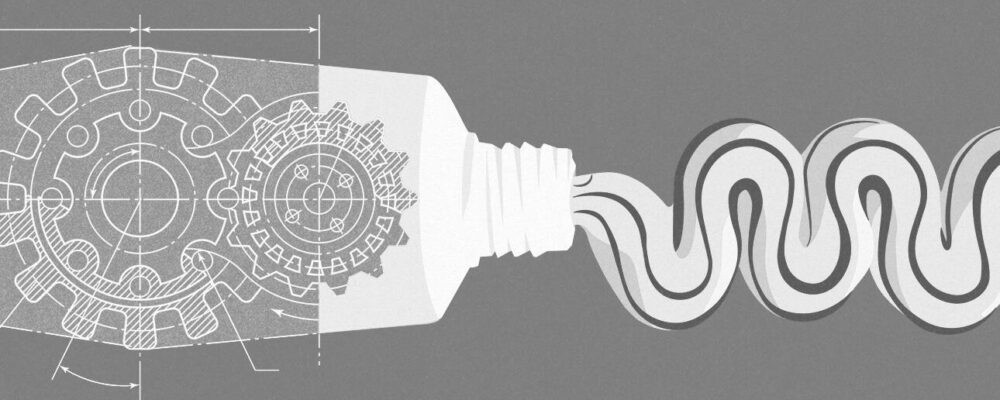

During the past few years, we have conducted several research studies examining the effectiveness of various types of allyship interventions and have assessed the pros and cons of each. Drawing from this work, we constructed a framework for goal-directed allyship.

By applying this three-part framework, leaders can identify specific goals to focus their allyship interventions on, such as effectively addressing transgressions, advancing marginalized employees, and scaling up allyship.

1. Addressing Transgressions

A relatively visible incident of bias is a situation that calls for leaders to immediately intervene, such as when a person makes a sexist comment in a public forum. The most common allyship goal in such an instance is to address the transgression by holding the transgressor accountable and educating them about what behaviors are (un)acceptable in the organization. Past research has shown that direct confrontation by publicly calling out bias can be an effective intervention in reducing similar incidents in the future by the transgressor as well as the onlookers.

However, our research has shown that while confrontation is certainly better than inaction, three unintended negative consequences can occur. First, the callout increases some onlookers’ victim-blaming, possibly doing more harm than good for the very people the ally is striving to support.

Reprint #:

“The MIT Sloan Management Review is a research-based magazine and digital platform for business executives published at the MIT Sloan School of Management.”

Please visit the firm link to site