A few months ago, Marcus Crook had an idea for the Melbourne streetwear label and social enterprise HoMie, where he is co-founder and creative director.

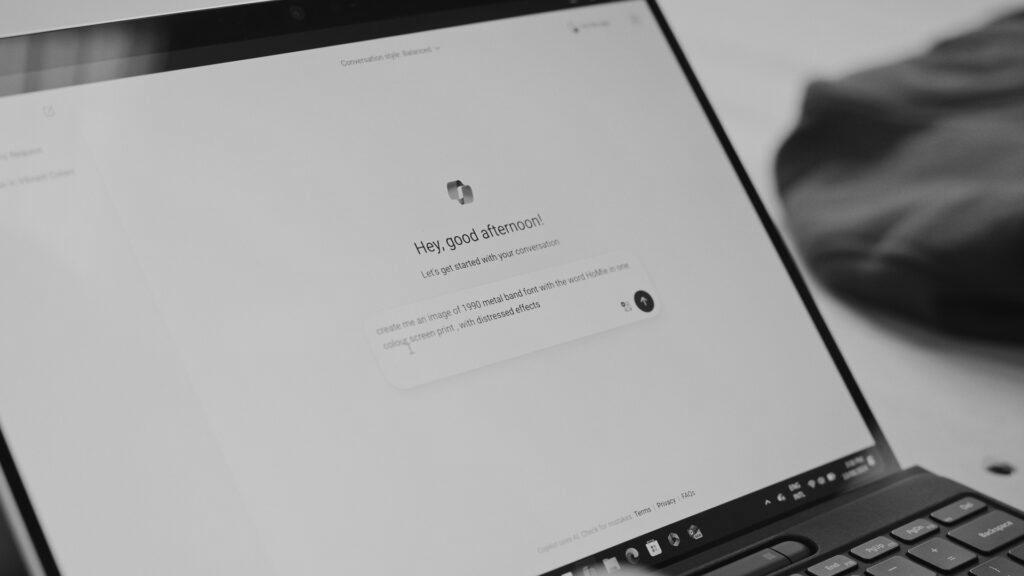

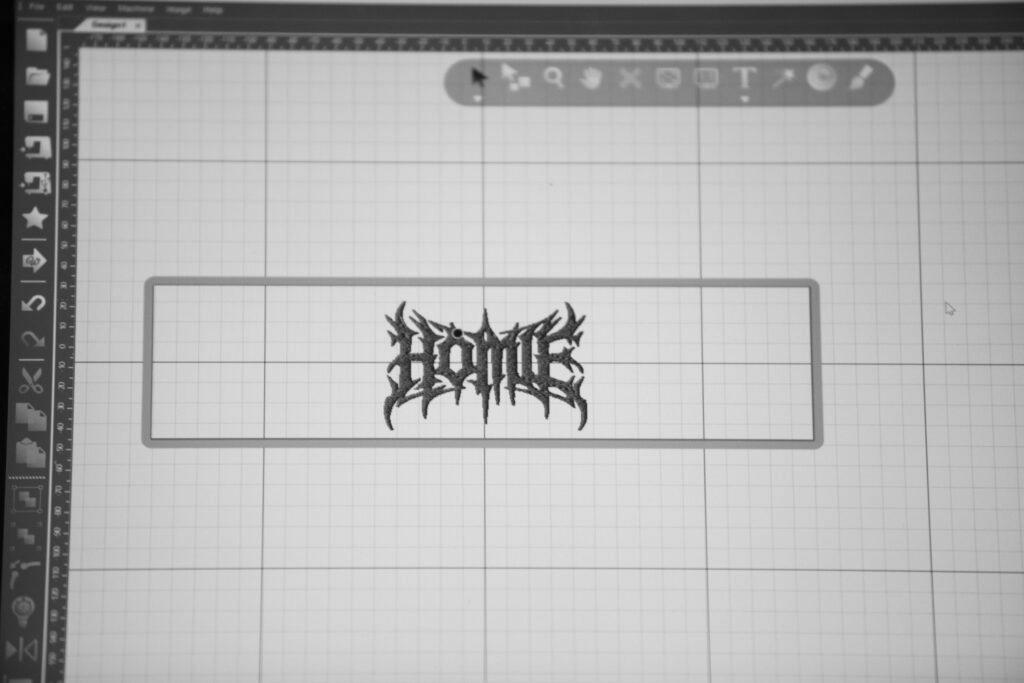

He opened Microsoft Copilot in Windows and typed: “1990s metal band style font with the word ‘HoMie’ in one color screenprint, with distressed effects, black font on a white background.”

Copilot, a generative AI assistant, produced some simple, cartoon-like images, which Crook transferred into editing software. Then he began manipulating and massaging angles, giving the final design a sculptural, spidery effect. He reckons the process took a total of two hours for something that might have taken two days. An embroidered sweatshirt with that design – the Gothic Crewneck, in teal – is now on sale on HoMie’s online store, where all proceeds go to its mission of helping young people affected by homelessness or hardship.

Crook is well aware he’s wading into controversial territory in the age of generative AI.

“Some people have concerns around authenticity and there’s a lot of people that haven’t had the tools to give it a go,” he said. For him, Copilot is a way to “get those ideas out of your head” and onto a drawing board, where the real work begins.

A leg up

Generative AI tools, built on large language models (LLMs) that synthesize massive amounts of data to generate text, code, images, and more, are seen as the biggest technological leap since the web browser and the smartphone.

At the same time, because of their ability to generate in seconds what might have taken someone much longer to write, draw, code, or otherwise create, some in the creative community have raised concerns about how these tools will affect their livelihood.

Last year, Microsoft gave Crook a Surface Laptop Studio 2 as part of the device’s marketing roll-out with social media influencers in Australia. Earlier this year, he began using Copilot.

The way Crook sees it, people are already drawing inspiration from anywhere, including from images across the web. “I’m using my own thoughts to start the inspiration process, but it’s important to me that it is just the start of the journey.”

[embedded content]

Crook and his friends started HoMie ten years ago to connect young people affected by homelessness with resources like donated clothes and free haircuts. Today, HoMie and its sub-label REBORN work with high street brands to repurpose their excess stock, saving them from landfills, with proceeds going to social impact programs.

The upcycled designs – some practical, some whimsical and usually unrecognizable – go back onto the shop floor at partner retailers and onto the runway at local fashion festivals.

Melbourne regularly ranks among the most livable cities in the world. But even here, the number of people experiencing homelessness is rising, with the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ 2021 census recording 30,0660 affected by homelessness in the state of Victoria, making up just over a quarter of all people affected by homelessness across Australia. Up 24 percent from five years earlier.

Crook, who grew up in a country town outside Melbourne, moved to the city to play football. He then worked various jobs – photographer, videographer, and retail assistant.

On lunch breaks while working at a clothing store, Crook and his friends started chatting with people affected by homelessness, hearing their stories on how chance and circumstance can land someone on the street.

One Christmas, Crook and others who would become fellow founding members of HoMie, set up a pop-up shop of donated clothing for those who needed them. Ten years later, the social enterprise has a team of 15 people and operates a shop on Melbourne’s Brunswick Street with its own line of streetwear.

HoMie offers paid internships to young people affected by homelessness where they get vocational training including paid work at high-street retailers, coming away with an accredited certificate in business. And almost 60 young people have completed the eight-month paid internships.

In addition, some 3,200 young people have come through to “shop” for free, get a haircut, and a cup of coffee.

“For me, what’s really important is I have to be innovative and do what’s best for our organization,” Crook said. “If we can be more efficient in creating products, that time and money can be spent on our social impact programs.”

Lines in the sand

In addition to using Copilot as a starting point for new designs, Crook has also used it to create pitches for potential partners to show how the upcycled garments could look before they are even sewn. “I can present hundreds of ideas to brands in a matter of hours in what would previously take weeks,” he said. “It certainly helped getting brands onboard.”

Once the designs are finalized, “the real artistry occurs in the remaking and manufacturing process with extremely skilled machinists in our factory who bring the visions to life,” Crook said.

Crook has drawn lines in the sand. He doesn’t see a problem with using Copilot to generate flat-lay imagery of designs, or the bird’s eye view generally used for product photography. But he won’t use it to generate people, partly because of the potential problem of AI bias.

But he thinks creatives could benefit from copilots as another tool in their arsenal. Ultimately, “people will start seeing it [AI] as a tool and not an enemy that is going to take their jobs,” he said. “It will give people better outputs and help save time.”

Top image: Marcus Crook, co-founder and creative director, HoMie. Photo by Leigh Henningham for Microsoft.

Microsoft is a technology company, a small local company, with few employees, no offices, and almost making no profit… >>

Please visit the firm link to site