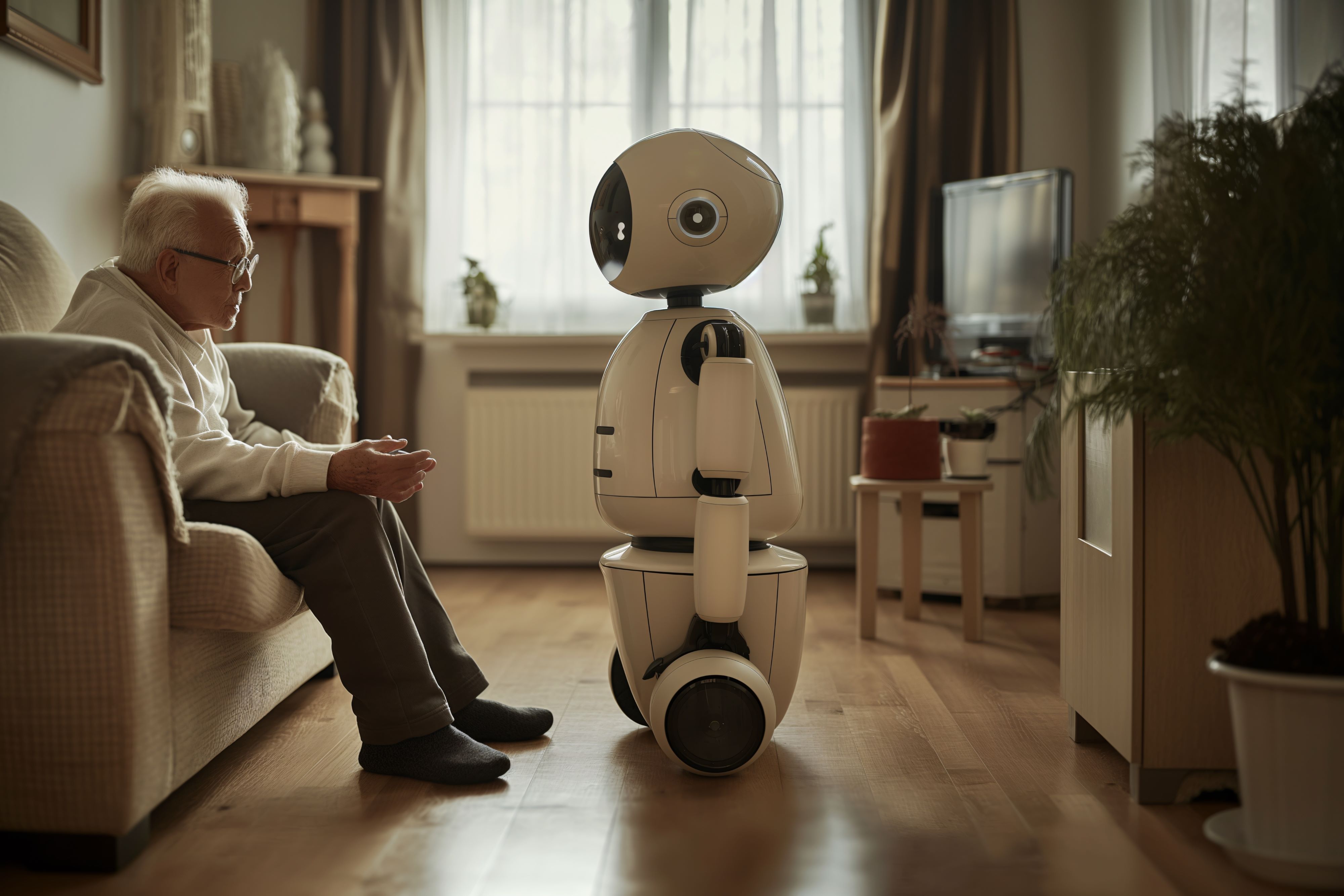

The study, published in the journal Community, Work and Family, assesses people’s attitudes towards having robots caring for oneself, providing services and companionship, when one is infirm or elderly. The study draws on data from 28 European countries, factoring in local determinants such as GDP, women’s labour force participation rates, and spending on elderly care.

The lead author, Professor Ekaterina Hertog, Associate Professor at the Oxford Internet Institute & the Institute for Ethics in AI, University of Oxford explains: “In our study we investigate three key questions: Are women more comfortable than men with being cared for by robots in their old age? Are those with greater time pressures and higher opportunity costs more supportive of receiving care from technology? And do macro-level factors inform individual attitudes to robotic care?”

The researchers find that individuals differ substantially in how comfortable they are with using technology to fulfil their care needs, with local context and personal factors shaping attitudes towards being cared for by robots.

Key findings of the study:

- Overall, people are not very enthusiastic about being cared for by robots.

- European men are more open to adopting robotic technologies for their own care than women when they get infirm or elderly.

- More educated men and women are more supportive of using robots for their own care.

- People working in professional, managerial or white-collar jobs are more supportive of using robots for their own care than those in non-professional occupations.

- Younger people and those with experience of using robots in work or domestic contexts are more open to using them in the future to help with their own care.

- Those living in local communities with higher levels of female employment and low levels of spending on adult care more likely to accept robots as part of their care package in old age.

It is also not all about personal characteristics, the researchers find. Their analysis highlights how peoples’ attitudes are informed not only by personal experiences, such as ability to pay, and shortage of time, but also, crucially, by local context, for example, by welfare provision available for older adults.

‘A key finding of ours was that local context really matters,’ stresses study co-author Professor Leah Ruppanner, University of Melbourne. ‘Those living in communities with higher levels of female employment and lower levels of spending on old age support were generally more comfortable with using robots for elderly care. Conversely, we find that when governments invest more heavily in elder care, people report (on average) being less comfortable with relying on robots in the home to provide care for the infirm and elderly.’

For policymakers, the research flags that they should be aware of are ‘tensions between a desire to meet adult care demands with human or technological labour. Technology should not be an inevitability. Rather, any investment into technological solutions needs to be evaluated against investing in support for paid or unpaid carers,’ adds co-author Brendan Churchill, University of Melbourne.

Looking ahead, the researchers stress the need for policymakers to evaluate the opportunity costs of any adult care technologies against human care provision. ‘When such digital care technologies are adopted, it is crucial we consider how adult care technologies can be integrated in a way that preserves, and ideally amplifies, the ability of human carers to maintain the connection with those they care for,’ maintains Professor Hertog.

‘Care technologies will only become more salient as populations age, women’s workforce participation increases and technology advances. The questions we need to ask are how comfortable are individuals with letting AI-powered technologies like robots take care of them? And what might be shaping their preferences?’

The full paper “Silicon caregivers: A multilevel analysis of European perspectives on robotic technologies for elderly care,” has been published in Community, Work, and Family.

“The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world’s second-oldest university in continuous operation.”

Please visit the firm link to site