Q: You are co-authors of “Is Your Use of AI Violating the Law?” published in the Journal of Legislation and Public Policy. What is the aim of the paper?

Chertoff: The idea was to survey various ways in which artificial intelligence is impacting the legal landscape. What are the responsibilities of those developing AI technologies? What are the rights of those at the receiving end of decisions made or assisted by AI? What liabilities do users of AI tools have? What are the intellectual property issues raised by AI? What are the security issues?

Vogel: A big part of our intent was to establish what the risks are so that we can all proceed thoughtfully. Secretary Chertoff and I both want AI to realize its potential. We both happen to be very excited about the way AI can create more opportunity. We want AI to benefit more women, more people of color, more of society and more of our economy, but we see people are fearful, intimidated by AI, and not feeling like it’s a language or a medium in which they can operate.

Q: Where is the fear is coming from?

Chertoff: Technological change is always disruptive and always unnerves people. But beyond that, it’s easy to understand an algorithm which is programmed, but a machine that can learn and develop rules for itself—that’s scary to some people.

Vogel: Add questions like, Will I have to learn new skills to keep up with AI? Will AI take my job? What kind of jobs will be available to my kids?, and people are understandably worried about their own fate and their children’s livelihoods.

At the same time, TV and movies show us almost exclusively worst-case scenarios. While that’s what’s successful at the box office, it’s the primary or only experience many people have visualizing these technological systems in society.

Taken together, the real concerns and worst-case imagining are, in some ways, creating this harmful self-fulfilling prophecy. If too few people feel comfortable engaging with AI, the AI that’s developed will not be as good, it will benefit fewer people, and our economy will not benefit as broadly. To get the best outcomes from AI, we need broad and deep engagement with AI.

Q: Why is that?

Vogel: AI is constantly learning and iterating. It gets better through exposure to people wanting different things, seeking different experiences, having different reactions. If it’s trained on a population of users that’s includes a full range of perspectives, backgrounds, and demographic groups, we get a more capable AI. While if an AI system interacts with a small slice of the population, it might meet the needs of that group perfectly while being problematic for everyone else.

Q: What are the uses of AI that are most promising to each of you?

Chertoff: To me, what artificial intelligence allows you to do is screen a huge volume of data and pick out what is significant. For example, in my old department, Homeland Security, you’re concerned about what people might be bringing in across the border by air or by sea. Artificial intelligence can help by flagging patterns of behavior that are anomalous. Or if you’re worrying about insider cybersecurity threats, AI can recognize data moving in an unusual way.

AI can analyze data in a way humans cannot, but humans need to be making decisions about what the AI finds because AIs still make fundamental errors and end up down a rabbit hole. The capacities human beings bring to analysis and decision making—skepticism, experience, emotional understanding—are not part of AI at this point.

Vogel: Two areas where I see promise but also concerns are healthcare and education. In healthcare there’s an AI tool called Sybil, developed by scientists at Mass General Cancer Center and MIT, which according to one study predicts with 86% to 94% accuracy when lung cancer will develop within a year. As somebody who had two aunts die way too early from lung cancer, that takes my breath away. A year’s advance notice is just mind blowing.

But any healthcare applications of AI need standardized metrics, documentation, and evaluation criteria. For whom is this AI tool successful? Did the tool give false negatives? Was the data the AI trained on over- or under-indexed for a given population? Do the developers know the answers to those questions? Will healthcare providers using the tool know? Will patients know? That transparency is crucial.

Likewise, in education, there are some really interesting use cases. For example, the Taiwanese government launched a generative AI chatbot to help students practice English. It’s a great way to get students comfortable with the language in their own homes. However, we need to be mindful to test for potential risks. For example, an AI system can reflect the implicit biases in the data they’re designed or trained on. For example, AI systems could unexpectedly teach racist and sexist language or concepts. They can hallucinate. It would be problematic if a student were exposed to a biased or hallucinating AI, and so we would want to ensure sufficient and thoughtful testing as well as adult supervision.

Q: Both of you offered examples of exciting, valuable uses of AI—then added significant caveats.

Vogel: If we approach AI with our eyes open and feel empowered to ask questions, that’s how we’re all going to thrive.

Often, when I’m talking to an audience I’ll ask, “How many of you have used AI today?” Usually, half of the audience raises their hand, yet I’m quite sure almost all of them have used AI in some way by the time they’ve gotten to that auditorium. Their GPS suggested an efficient route to their destination or rerouted them to avoid traffic. That’s AI. They checked the newsfeed on their phone. That’s powered by AI. Spotify recommended music they’d enjoy based on prior selections. That’s AI.

If done well, regulation engenders trust and enables innovation. Appropriate clarification of expectations, definitions, and standards is something that benefits all of us. We should be thinking about what will make sure AI develops in a way that benefits society.

AI abstinence is not an option. It’s our world now. It’s not our future; it’s our present. The more we understand it’s not foreign, it’s something we’re using and benefiting from every day, the more we’ll feel agency and some enthusiasm for AI.

I hope people will try generative AI models and look at some deepfake videos. The more we engage, the more we’ll be able to think critically about what we want from AI. Where is it valuable and where does it fall short? For whom was this designed? For what use case was this designed? And so, for whom could this fail? Where are there potential liabilities and landmines?

That doesn’t mean we all need to be computer scientists. We don’t need to be mechanics to drive a car. We don’t need to be pilots to book a ticket and fly across the country safely. We do have a vested interest in making sure that more people are able to engage, shape, and benefit from AI.

Q: How should organizations think about deploying AI?

Chertoff: I developed a simple framework—the three Ds—which can guide how we think about deploying AI. The three Ds are data, disclosure, and decision-making.

Data is the raw material that AI feeds on. You have to be careful about the quality and the ownership of that data. People both developing AI must comply with rules around the use of data, particularly around privacy and permissions. That’s just as true for people deploying AI within a company. Will the AI access company data? What are the safeguards?

Another data example: there’s ongoing debate about whether training AI on published works is an invasion of copyright or fair use. Human beings can read a published work and learn from it. Can AI do that or is it in some way a misuse of intellectual property? That’s still being argued. Developers and organizations deploying AI will want to stay aware.

With disclosure, it’s important to disclose when AI is performing some function. I wouldn’t go so far as to say you can’t create deepfakes, but I would say the fact that it’s not genuine needs to be disclosed.

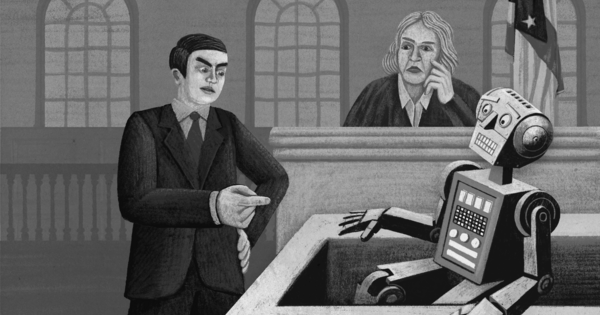

And finally, decision-making. I’m of the view that when it comes to making a decision that affects the life of a human being—hiring, firing, release from prison, launching a drone strike—whatever AI may tell you, a human being has to be the final decision-maker. We don’t entrust matters of life, death, or great human consequence to a machine.

Q: Are companies using AI potentially liable for problems?

Vogel: Any company using AI, particularly in spaces where federal agencies have said they plan to have oversight, needs to make sure that they’re compliant with existing laws on the books. We don’t want people to have the false sense that they are absolved of liability because they’re an end user.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has put employers on notice that they will be liable for AI systems used in employment decisions. For example, iTutor settled a case brought by the EEOC alleging that the AI-enable recruiting software they used rejected older applicants. A Federal Trade Commission case against Amazon led to a $25 million fine and requirement for algorithmic disgorgement—removing inappropriate data from their algorithms—after Alexa allegedly kept voice and location data that violated child privacy law. Meta received the maximum penalty under the Fair Housing Act for algorithmic bias after advertisements were displayed only to specific populations and demographics, violating civil rights protections.

On top of settlements, there are reputational costs from having been associated with harmful and discriminatory uses of AI.

Chertoff: We’re also going to increasingly see common law, tort law, and contract law being engaged because the uses of AI cut across all kinds of personal and business activities. Since that involves, by and large, state courts, it’s going to vary. California has been very energetic in pushing on state law claims that could be used with AI cases.

Vogel: In the last six years, we’ve seen a six-fold increase in litigation. AI has the potential to be involved in wide-scale harms and the companies creating and using the tools have deep pockets.

That combination means savvy lawyers will likely increasingly use the laws on the books today to address and remedy these incidents.

Asking whether a deepfake constitutes a fraud may be a new question, but our legal system was set up to adapt to new technologies and new circumstances.

Chertoff: That isn’t to say it won’t be complicated. If we think about liability from a harm created by an AI product, typically, the question would be, who is best situated to prevent the injury? We might think about the user, the retailer, the manufacturer or the designer of a product that uses AI. Depending on the circumstances, we might follow the chain back to the developer of the AI or even whoever supplied the data that trained the AI. The question of how to allocate liability among all those different actors is going to take a while to really sort out.

Q: Some AIs are black boxes—even the developers do not know how they reach decisions. How is that addressed in a legal context?

Vogel: We have seen judges try to grapple with this in both the developer and the deployer context. In some cases, they’ve shown deference—it’s hard to assign liability to someone who can’t know what’s in that black box. But increasingly we’re seeing courts not accepting that answer. Judges are learning to solve the black box problem with tools like algorithmic disgorgement and limited discovery around code and training data to make sure there is enough clarity for a more just outcome.

Chertoff: One additional factor is the extent to which the law evolves to create strict liability, which means basically it doesn’t matter whether you knew the black box AI had a problem. You bought the black box, you own the result, and you’re going to have to pay for it.

Q: Are there areas where new legislation or regulations would be valuable?

Vogel: Regulation is now a bad word, yet, if done well, it engenders trust and enables innovation. It’s a significant part of why we feel safe getting in a car or airplane.

So I think we should embrace the fact that appropriate clarification of expectations, definitions, and standards is actually something that benefits all of us. We should be thinking about what will let us use AI safely. What will make sure AI develops in a way that benefits society.

Here’s one straightforward example. We have a system for reporting cyber incidents. While it’s not perfect, we absolutely need something similar in AI. Right now, there’s no formal mechanism to report issues in a way that allows the federal government to understand what’s happening and companies to know what to be on the lookout for.

Chertoff: I’d be careful about not rushing ahead with anything comprehensive, but I do think on issues of transparency—disclosure about what the algorithms are, what the artificial intelligence does—some regulation would be beneficial.

Safe harbor would also be valuable. With counter-terrorism technologies, liability is capped, even if there are failures, if developers have gone through a discipline process and satisfied specific requirements while developing the technology. Something similar might be useful for AI.

Q: What do these issues look like from a global perspective?

Vogel: AI doesn’t have borders. So it’s important that companies aren’t going to run into problems with inconsistencies in the expectations and regulations.

Increasingly we’re going to see AI used as a weapon by our adversaries. That’s going to require the creation of defenses: a capability to blunt a disinformation attack in a way that’s consistent with our law, but also protects us from people who are operating off a different playbook.

A significant portion of our paper looks at different approaches to AI regulation and policymaking in different parts of the globe. We discuss the different approaches of the EU, UK, Singapore, and others.

Chertoff: It’s important to synchronize the regulations so that global enterprises don’t have to basically compartmentalize activities in each country or region. That’s difficult to do, easy to mess up, and would undermine some of the value of AI.

But that’s going to be a real hornet’s nest for two reasons. First, among what I would call our like-minded allies, there are still different standards. The Europeans are much more willing to regulate data and AI than the United States has been.

On the other extreme, increasingly we’re going to see AI used as a weapon by our adversaries. That’s going to require not a commonality of law—because we’re not going to get the Russians to buy into our legal system—but the creation of defenses: a capability to blunt a disinformation attack in a way that’s consistent with our law, but also protects us from people who are operating off a different playbook.

Q: Are there specific lessons we can take from other periods of technological change that would be worth bringing to front of mind?

Vogel: Having done this survey, I believe that people will see the tool set to address AI risk is going to be roughly comparable to risk management for other technologies. EqualAI has created a resource library to help organization with Good AI Hygiene and other tools to help govern their AI systems.

At the same time, the fact that AI is impacting every industry with use cases across the globe—it makes me think of the way the internet has changed communication and commerce, or how electricity changed the way so many systems operated. We should be prepared for the possibility that AI will have that order of impact.

Chertoff: There are likely to be unanticipated dimensions going forward. We’ve seen, in other technology areas, a revisiting of some of the initial assumptions. The internet and social media were originally conceived as means to connect people to one another that would be wonderful for democracy. Now there’s a considerable view that they’re being used by autocrats to drive authoritarianism and undermine democracy. And we’re debating the responsibilities of platform operators in terms of content on their platforms.

We do learn sometimes that the downsides are perhaps underestimated with a new technology, but the good news is we have the ability then to amend or modify the rules. The legal method is to learn lessons from real life and make modifications when the need arises.

“The Yale School of Management is the graduate business school of Yale University, a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut.”

Please visit the firm link to site