In the midst of negotiations over the budget bill, part of which had already been rejected by the centre-left opposition, which holds a parliamentary majority, President Yoon Suk Yeol decreed martial law, prohibiting all political activity and rallies and putting the press under the control of the army. This extremely surprising and inordinate power grab – a tactic widely used by the authoritarian military regimes that ruled the country from its independence in 1948 to the late 1980s – could have brought South Korea face to face with its old demons.

To justify his decision, the president said he wanted to protect the country from “the threat of North Korea’s communist forces”, “eradicate anti-state forces that shamelessly align with pro-North elements and plunder the freedom and well-being of our people” and “safeguard the free constitutional order”. He was referring to opposition members of parliament, who have held a majority since the parliamentary elections of April 2024, creating a situation – unprecedented in South Korea – where the president does not command a parliamentary majority.

Negotiations over the 2025 budget have proved particularly turbulent, with President Yoon accusing the Democratic Party of cutting “all key budgets essential to the nation’s core functions, […] turning the country into a drug haven and a state of public safety chaos”. Another bone of contention was a vote – also brought by the opposition – to impeach the Chief Auditor, tasked with auditing the accounts of state and administrative bodies and of some public prosecutors.

The opposition wasted no time in reacting. After gathering for an emergency meeting, the Democratic Party’s 170 members of parliament managed to enter the parliament building – closed off and guarded by the army – and pass a resolution calling for martial law to be lifted. Backed by twenty members of parliament from other parties, the resolution was passed unanimously by all present, representing a majority of all members (190 out of a total of 300). The vote was authorised and validated by the parliamentary speaker and was in keeping with the constitution, which stipulates that if a law is voted down, it must immediately be lifted by the president.

Despite restrictions imposed by martial law, tens of thousands of people also gathered outside parliament to condemn President Yoon’s attempted power grab. Trade unions called for an indefinite general strike and the leader of the presidential party declared the law unconstitutional.

Backed into a corner, the president admitted defeat and withdrew the decree imposing martial law. His main collaborators (his chief of staff and national security advisor) tendered their resignation and the army withdrew.

Market impact: while the worst has been avoided, volatility could set in

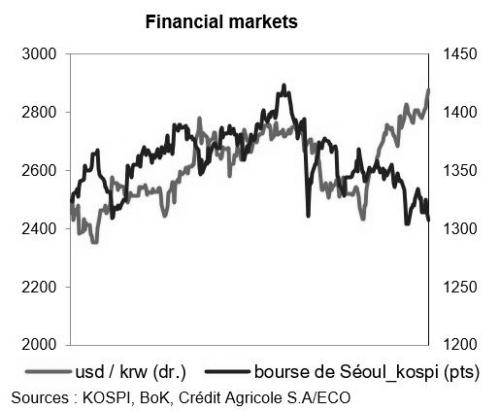

The Korean won (KRW) lost some ground following President Yoon’s announcement, with the exchange rate falling below KRW 1,400 to the dollar and sinking as low as KRW 1,425 to the dollar. Stock market indices declined slightly (down 1.4%) when the Seoul stock exchange – already closed when Yoon made his declaration – reopened on 4 December. This market reaction was to be expected and could have been even more pronounced: the impact was limited by the opposition’s quick response, the mobilisation of civil society and the withdrawal of the decree. By the end of the week, the Korean won had lost just over 1% against the dollar, the Kospi stock market index had lost around 3.5% and the spread to US Treasuries had risen by just over 4%.

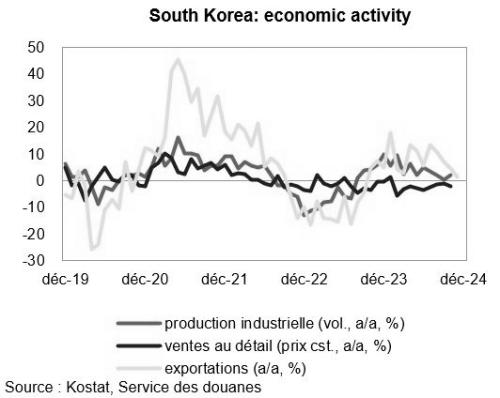

This is good news: South Korea’s economy could do without high volatility in its currency, already struggling relative to other Asian currencies. The Korean won has lost 10% of its value since January 2024, making it Asia’s second worst performing currency after the Japanese yen. Last week, South Korea’s central bank announced an unexpected interest rate cut2, basing its decision on slowing economic activity and the stabilisation of inflation.

Already faced with a number of trade-offs and seeking to prevent the won from depreciating too quickly, the central bank would have been forced to intervene if the currency shock had been any more powerful. Although it has substantial currency reserves ($415 billion, equivalent to 25% of GDP), committing to a policy of defending your currency during a period of high volatility is always a risky business and can even end up being counterproductive. Keen to reassure investors, South Korea’s finance minister also said the government and the central bank would provide interbank markets with liquidity for as long as necessary.

Now that the motion to impeach has failed, what are the options?

As allowed by the constitution, opposition members of parliament immediately filed a motion to impeach the president, which was put to the vote on 7 December. To reach the 200 votes (two-thirds of the National Assembly) needed to impeach the president, Democratic Party members needed to enlist the support of eight members of the presidential party. In the end, only three conservative members of parliament stayed in the chamber and voted for the motion. The rest left to block a quorum, making the outcome invalid whichever way the vote went. The opposition is already planning to put forward a similar motion again on 11 December. President Yoon, more or less hidden from view since his statement on 3 December, presented his “sincere apologies” to the people of South Korea and explained that his action had been “a desperate decision made by me, the president” for which he would “not avoid legal and political responsibility”. He also promised that he would not seek to impose martial law a second time.

So overwhelming are the facts against Yoon that it is increasingly hard to imagine how he can possibly remain in power: in reality, his declaration of martial law – which had the appearance of a hasty decision – was accompanied by a plan to neutralise key opposition figures as well as some media outlets and was based on the idea that the parliamentary elections in April had been rigged by the Democratic Party.

Seventy-five percent of South Koreans are now demanding Yoon’s resignation, with hundreds of thousands demonstrating since 3 December. While prime minister Han Duck-so has promised to stabilise the situation, it is looking increasingly hard to escape the conclusion that Yoon is going to have to go. Moreover, were he to end up in prison, he would not be the first president to do so: his predecessors Lee Myung-bak (2008-2013) and Park Geun-hye (2013-2016) were both convicted in corruption cases. With the charges against him – including “treason” – much more serious, Yoon would risk life in prison.

Although this (bad) Korean soap opera is surely far from over, there is one positive point worth noting: South Korea’s young democracy held firm and people immediately sprang into action to defend their rights and freedoms. Even the army, whose very nature is to follow orders, appeared uneasy about the president’s power grab and limited its response to the bare minimum: while soldiers guarded Parliament, they did not bend over backwards to stop members entering the building to vote to repeal martial law, nor did they disperse protestors by force.

The rest is a bit more worrying. This episode will take its toll on the presidential party, driving a wedge between those who want to hold onto power and those who don’t. And, since markets always take a dim view of uncertainty, it will also leave its mark on the economy. On 9 December, the Korean won fell to a new record low of less than KRW 1,430 to the dollar.

“Crédit Agricole Group, sometimes called La banque verte due to its historical ties to farming, is a French international banking group and the world’s largest cooperative financial institution. It is France’s second-largest bank, after BNP Paribas, as well as the third largest in Europe and tenth largest in the world.”

Please visit the firm link to site