Charterhouse Warren is one of those rare archaeological sites that challenges the way we think about the past. It is a stark reminder that people in prehistory could match more recent atrocities and shines a light on a dark side of human behaviour. That it is unlikely to have been a one-off event makes it even more important that its story is told.

Professor Rick Schulting (School of Archaeology, University of Oxford)

The new study, which involved researchers from several European institutions, analysed over 3000 human bones and bone fragments from the Early Bronze Age site of Charterhouse Warren, England. These were discovered in the 1970s in a 15m-deep shaft. The bones came from at least 37 individuals: a mix of men, women, and children, suggesting the assemblage was representative of a community.

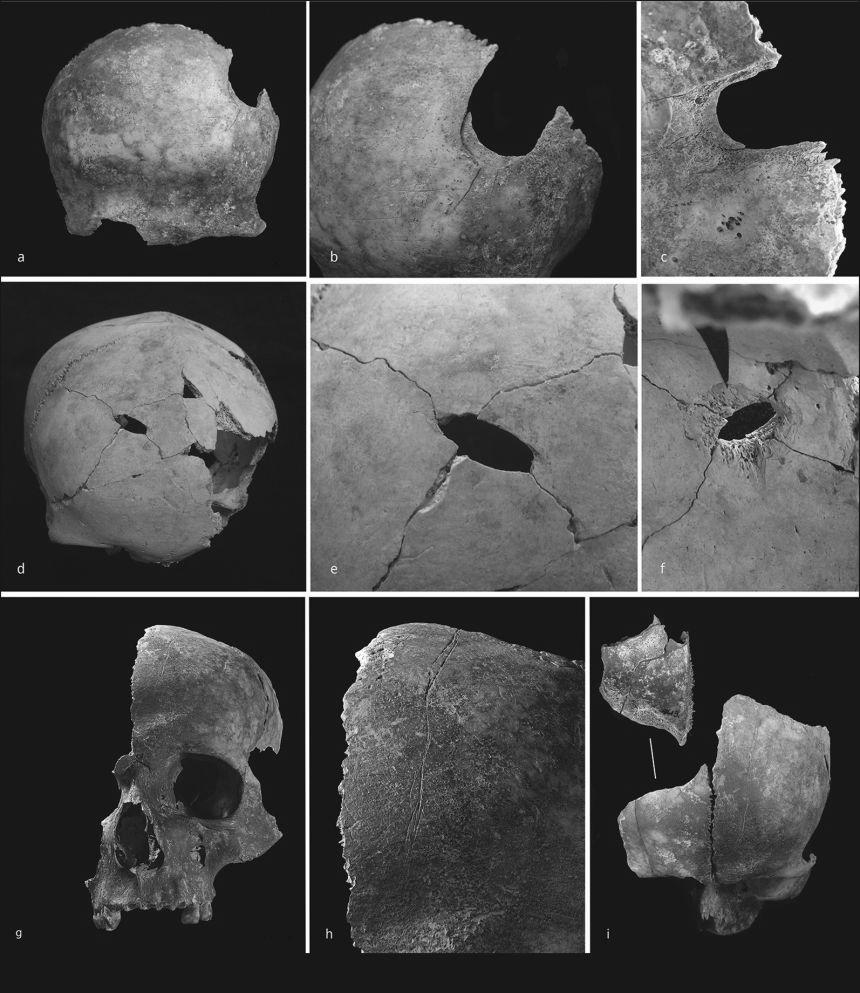

Unlike most contemporary burials, the skulls display evidence of violent death from blunt force trauma. There have been hundreds of human skeletons found in Britain dating between c.2500-1500 BC, however, up to now, direct evidence for violent conflict has been rare.

‘We actually find more evidence for injuries to skeletons dating to the Neolithic period (10000 BC – 2200 BC) in Britain than the Early Bronze Age, so Charterhouse Warren stands out as something very unusual’, stated lead author of the research, Professor Rick Schulting (School of Archaeology, University of Oxford). ‘It paints a considerably darker picture of the period than many would have expected.’

In the new analysis, the researchers found numerous cutmarks and perimortem fractures (made around the time of death) on the bones, suggesting that they were intentionally butchered and may have been partly consumed. But why would people in Early Bronze Age Britain cannibalise the dead?

Cutmarks on distal left humerus. Credit: Schulting et al. Antiquity, 2024.

Cutmarks on distal left humerus. Credit: Schulting et al. Antiquity, 2024.

At the nearby Palaeolithic site of Gough’s Cave in Cheddar Gorge, cannibalism was likely a form of funerary ritual. Charterhouse Warren is different, however. Evidence for violent death, with no indication of a fight, implies the victims were taken by surprise. It is probable they were all massacred, and the butchery was carried out by their enemies.

Were they killed for food? This is unlikely. There were abundant cattle bones found mixed in with the human ones, suggesting the people at Charterhouse Warren had plenty to eat without needing to resort to cannibalism.

Instead, cannibalism may have been a way to ‘other’ the deceased. By eating their flesh and mixing the bones in with faunal remains, the killers were likening their enemies to animals, thereby dehumanising them.

What events led to this dramatic act of violence? Resource competition and climate change don’t seem to have exacerbated conflict in Britain at this time, and there is currently no genetic evidence to suggest the co-existence of communities with different ancestries that could have resulted in ethnic conflict.

This suggests that the conflict was caused by social factors. Perhaps theft or insults led to tensions, which escalated out of proportion. Evidence for infection with plague in the teeth of two children indicates disease may have also exacerbated tensions.

‘The finding of evidence of the plague in previous research by colleagues from The Francis Crick Institute was completely unexpected’, said Professor Schulting. ‘We are still unsure whether, and if so how, this is related to the violence at the site.’

Ultimately, the findings paint a picture of a prehistoric people for whom perceived slights and cycles of revenge could result in disproportionally violent actions.

‘Charterhouse Warren is one of those rare archaeological sites that challenges the way we think about the past’, Professor Schulting concluded. ‘It is a stark reminder that people in prehistory could match more recent atrocities and shines a light on a dark side of human behaviour. That it is unlikely to have been a one-off event makes it even more important that its story is told.’

The study ‘The darker angels of our nature’: assemblage of butchered Early Bronze Age human remains from Charterhouse Warren, Somerset, UK’ has been published in Antiquity.

Examples of skulls from the assemblage, with evidence for blunt force trauma and cut marks. Credit: Schulting et al. Antiquity, 2024.

Examples of skulls from the assemblage, with evidence for blunt force trauma and cut marks. Credit: Schulting et al. Antiquity, 2024.

“The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world’s second-oldest university in continuous operation.”

Please visit the firm link to site