For many contemporary readers, their first introduction to the poetry of W.H. Auden came not in a course on English literature, but from a more mainstream source: the film Four Weddings and a Funeral, in which a character recites Auden’s 1937 poem Funeral Blues during the titular funeral.

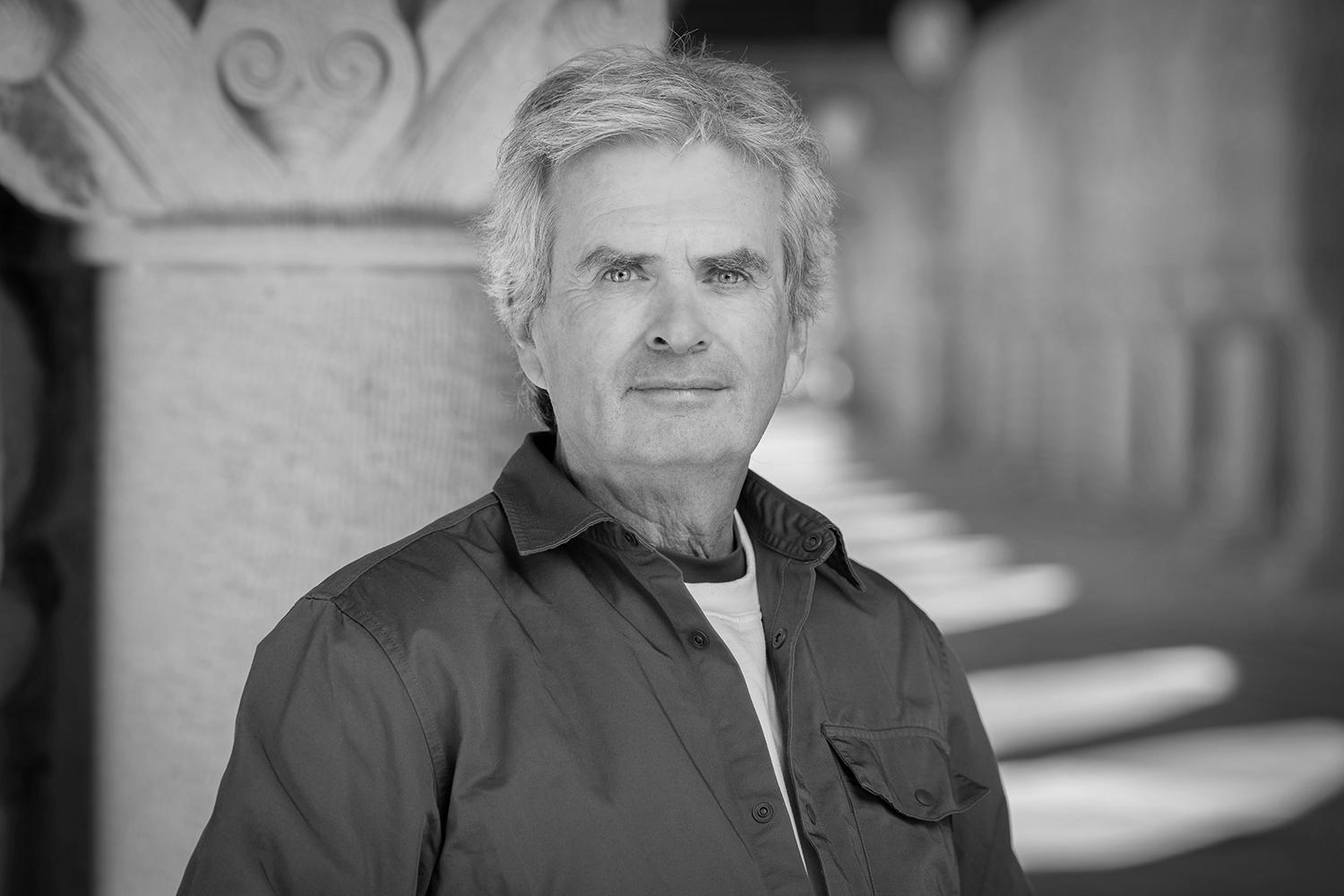

“It’s incredibly touching that a poet can write some words that continue to reverberate in the minds of people who don’t think of themselves as poetry lovers,” said Nicholas Jenkins, associate professor of English and director of the Creative Writing Program in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “That lyric has really meant something in a lot of people’s lives.”

With his new book, The Island: War and Belonging in Auden’s England (Belknap Press/Harvard University Press), Jenkins delves into the early life and work of the poet and establishes why we care about Auden nearly a century later, both in pop culture and academia. The book blends biography with history and critical analysis, placing Auden firmly within England between the wars and ending with him abandoning his home country for a nomadic, international lifestyle. This owes in part to Auden’s existence as a globally minded gay man at a time of rising nationalism and overt homophobia (in England and elsewhere). Jenkins describes these conflicts while providing insights into Auden’s poetry from this period.

According to Edward Mendelson, Auden’s literary executor and editor, the book is “a Copernican revolution” in our understanding of the poet. And in the Nov. 15 London Times Literary Supplement, the British edition of The Island was named a 2024 book of the year.

Here, Jenkins discusses how his book came to be and what Auden can tell us about our own era, in which nationalism is once again on the rise.

This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

This book focuses on Auden’s life from roughly age 15 to 30. Why did you focus on the years between 1922 and roughly 1937?

The patterns of a person’s mind are laid down in the early part of their life. In Auden’s case, a lot of the things that preoccupied and inspired him throughout his artistic career really came into being right at the beginning of the period when he started writing poetry, in 1922 when he was 15.

The book begins just a little way after the end of World War I, which Auden was haunted by, even though he always insisted that he wasn’t. And I stopped just before World War II broke out, when it was an ominous pall hanging over many people in the 1930s, including Auden.

Why end in 1937 or so?

That was the moment when a whole cycle in Auden’s artistic life ended and a new one began. He started traveling a lot outside England because the place where he’d grown up began to seem barren for him as an artist and a poet. I am writing a second book now about the new cycle that opened in Auden’s life as a poet around 1937.

How does The Island approach Auden?

I see Auden as a representative figure for a lot of characteristics of English culture and society. Some of them are interesting; some of them are beautiful; some of them are, morally, very compromised.

There’s been a tendency in writing about Auden to treat him as a pseudo-philosopher or a pseudo-historian. I think the most important thing about Auden – and I think Auden would have said this himself – is his writing poetry and being an artist.

There’s a quote from Auden that says, “Nationalism fails not because the nation is too small a group, but because it is too large.” So I’m wondering, in working on the book, did you notice any resonance with our world today, when nationalism is seemingly on the rise here and elsewhere?

Yes, definitely. It’s interesting: Poems are often about something that they never mention. And sometimes they’re about things that have not yet happened. As someone remarked to me, The Island is a Brexit book, among many other things, though the ugly word “Brexit” is never used.

How so?

It’s about somebody – in this case, Auden – who finds the idea of the island enclave as a form of separation from the rest of the world both seductive and troubling. And this “island existence” is a daydream or fantasy that has haunted English culture for centuries. We’ve lived through its re-emergence once more in the last few years.

So Auden was writing about a myth that continues to bewitch many English imaginations. And I think that is one of the marks of a great artist: that they continue to be understood in changing ways well into the future and that aspects of their work come into focus after they’re dead in a way that they couldn’t when the artist was alive.

When you study someone the way you’ve studied Auden, you must feel like you almost know him as a person. Given that, what do you think he would make of the political climate in 2024?

He would be deeply dismayed, but probably not surprised.

Part of your research included speaking with people who knew Auden. What was that like?

When I lived in New York, I did meet a lot of people who had been friends of Auden’s, and I talked to them about him. You feel a kind of historical responsibility if you’re a scholar in that position. The archive of living memory fades very rapidly for great artistic figures. I realized that I was hearing testimony from people who wouldn’t be around forever.

What did you learn from them?

That the real Auden is someone that nobody truly met except in his poetry. Hannah Arendt said it best: Auden had “the necessary secretiveness of the great poet.”

For more information

This story was originally published by the Stanford School of Humanities & Sciences.

“Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies 8,180 acres, among the largest in the United States, and enrols over 17,000 students.”

Please visit the firm link to site