Drawing the contours of the US (and therefore global) scenario requires making assumptions about both the scale of the measures likely to be implemented and their timing, depending on whether they fall within the prerogatives of the president or require the approval of Congress.

As far as tariffs are concerned, Donald Trump’s threats look like extreme pressure tactics. They call for an ‘intermediate’ scenario consisting of substantial increases, without however reaching the campaign proposals. Tariffs would thus rise to an average of 40% for China, from Q225, and to an average of 6% for the rest of the world, phased in over the H225. Aggressive fiscal policy, favouring tax cuts and maintaining extremely high deficits, would be implemented later: its effects could become apparent from 2026. In terms of immigration, restrictions could be applied from the start of the presidential term. They would be followed by a very sharp slowdown in immigration flows and, if deportations are to be expected, they would be ‘selective’ as opposed to a massive and indiscriminate removal of millions of people. Finally, deregulation, of which the energy and financial sectors would probably be the main beneficiaries, would spread its ‘benefits’ throughout Trump’s term in office.

Taken as a whole, these policy orientations should be favourable to growth. However, if the expected positive impact of aggressive fiscal policy and deregulation exceeds the negative impact of tariffs and immigration restrictions, it will follow. Given the resilience of the US economy, which is still expected to outperform forecasts to grow by around 2.7% in 2024, this suggests that growth will remain strong, albeit slightly weaker. Because of a few vulnerabilities (low-income households & small businesses are more exposed to high interest rates), our scenario assumes a slowdown to 1.9% in 2025, before a recovery to 2.2% in 2026: a development that should be accompanied by a revival in inflation. The end of the disinflationary path to the 2% target is the most difficult, and customs duties could put pressure on prices in a range of 25-30bp. Total inflation could therefore fall back to around 2% next spring, before picking up to around 2.5% by the end of 2025 and remaining there in 2026: the potential for monetary policy easing will be very limited.

In the Eurozone, the acceleration in growth over the summer gives reason to hope that the recovery will be only a modest one and that it will still be below potential and below the pace that will benefit the US. While the upturn in household consumption recorded over the summer augurs slightly stronger growth, the latest information on investment does not augur a marked acceleration. Falling inflation, which will boost purchasing power, but also a rebuilding of real wealth, implying a reduced savings effort, and lower interest rates, which will help to restore purchasing power for property: the ingredients are there for a continued recovery in household spending. But only at a very moderate pace, as fiscal consolidation and global uncertainty are likely to encourage a continued high savings rate. Our scenario therefore assumes a modest acceleration in consumption to 1.1% in 2025 and 1.2% in 2026, after 0.9% in 2024. After a sharp fall in 2024 (-2.1%), investment in 2025 is likely to remain penalised by the transmission delay of monetary easing but above all by weak domestic demand and growing uncertainty over foreign demand. Investment is expected to grow by just 1.5% before firming slightly in 2026 (2%).

The Trump administration’s policies would have a moderately negative impact on growth in the Eurozone, the most important short-term channel of which would be uncertainty.

The Trump administration’s policies would have a moderately negative impact on growth in the Eurozone, in the short term primarily due to uncertainty. Furthermore, the monetary and fiscal policy mix remains unfavourable to growth, with the key rate returning to neutral by mid-2025, while the ECB’s balance sheet reduction continues to be restrictive. The forecasts therefore put growth on a very soft acceleration trend, rising from 0.7% in 2024 to 1.0% in 2025 and then 1.2% in 2026: potential growth should be reached, but the output gap, which is slightly negative, should not yet be closed, while the growth gap with the US economy is expected to widen.

In EMs, if it were not for the difficulties associated with Trump 2.0, the situation would be improving: lower US key rates favouring global monetary easing, loosening pressure on EM FX and, more generally, on external financing for EMs; domestic growth buoyed by falling inflation and rate cuts; still buoyant exports to developed countries (primarily the US). But the effects of these supporting factors are likely to be undermined by the plausible repercussions of the measures taken by the new US administration. In addition to the tariffs likely to make EM exports more expensive and more limited, there will be less monetary accommodation in the US and a possible reduction in US military and financial support for Ukraine, fuelling geopolitical uncertainty in Europe. It is therefore preferable to be a large country with a low degree of openness, such as India, Indonesia or Brazil, a commodity-exporting country or an economy that is well integrated with China, which is preparing for the Trump storm.

In China, the last Politburo meeting concluded in December with a commitment by the authorities to implement a “more proactive” fiscal policy and a “sufficiently accommodating” monetary policy, to revive domestic demand and stabilise the property & equity markets. A period of trade tensions is looming and, apart from restrictions on exports of critical products (including rare earths), the tools of retaliation are limited: it is difficult to react by boosting the competitiveness of exports (the CNY is already historically low) or by reciprocally increasing custom duties, which would risk penalising already very fragile domestic consumption. The authorities’ intentions to provide more vocal support for domestic demand are commendable, but the effectiveness of this strategy will depend on household confidence: the rebound cannot be decreed, and our scenario continues to predict a slowdown in growth in 2025.

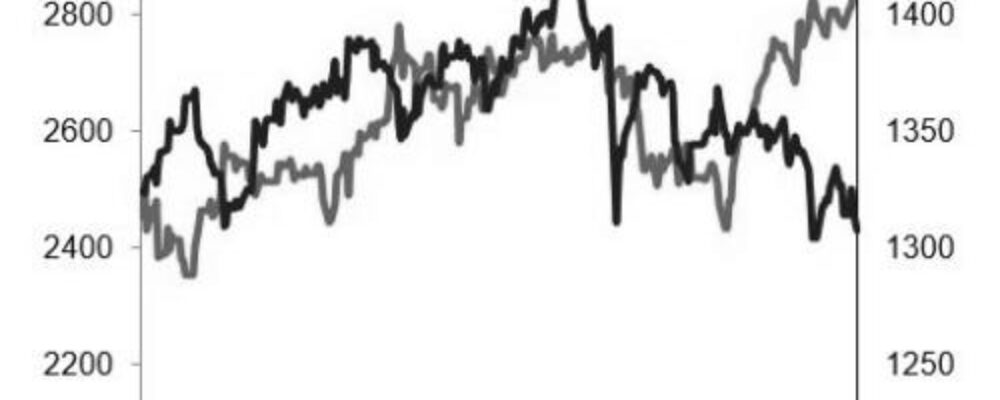

The market’s hopes of bold monetary easing have been refuted and are no longer on the agenda, particularly in the US. In an economy assumed to remain ‘resilient’, with inflation around 2% and then likely to pick up again, the easing would be modest. After a total reduction of 100bp in 2024, the Fed could ease by a further total of 50bp, taking the Fed Funds rate (upper limit of the target range) to 4.00% in H125 before pausing for a prolonged period.

As for the ECB, with inflation in line with target and no recession in sight, it would continue its moderate easing via its key rates, while extending its quantitative tightening. After its four 25bp cuts in 2024, the ECB could cut rates by 25bp at the January, March and April meetings, then maintain its deposit rate at 2.25%, ie, very slightly below the neutral rate estimate (2.50%).

Everything points to a scenario of a modest rise in interest rates. Given the economic scenario (limited slowdown in growth and moderate inflation concentrated at the beginning of the period) and modest monetary easing followed by an earlier pause, US interest rates could fall slightly in H125 before recovering. 10Y Treasury rates would move within a range of 4.20-4.50%. The new rate forecasts are higher than the previous ones and envisage a 10Y rate approaching 4.50% at the end of 2025 and around 5.00% at the end of 2026.

In the Eurozone, several factors point to a scenario of a slight rise in sovereign interest rates: market expectations of a bold monetary easing, where a correction could lead to a recovery in swap rates; an increase in the volume of government securities linked to the ECB’s reduction in the size of its balance sheet (quantitative tightening) and to still-high net issuance; and a diffusion of the rise in US bond yields to their European equivalents, expected at the end of 2025 and in 2026. While the German economy (where early elections are due to be held in February) continues to suffer, and the political situation in France struggles to become clearer, ‘peripheral’ countries have seen their good economic results (notably Spain) and their political stability (this applies to Italy and Spain) rewarded by a significant tightening of their spreads against the German 10Y rate in 2024: they should benefit from the same support in 2025. Our scenario therefore assumes German, French and Italian 10Y rates at 2.55%, 3.15% and 3.55% respectively at the end of 2025.

Finally, for the USD, several positive factors, including the currency’s attractiveness in terms of yield, have already been factored into its price. As a result, our scenario assumes that the USD will remain close to its recent highs throughout 2025, without overshooting them for long.

“Crédit Agricole Group, sometimes called La banque verte due to its historical ties to farming, is a French international banking group and the world’s largest cooperative financial institution. It is France’s second-largest bank, after BNP Paribas, as well as the third largest in Europe and tenth largest in the world.”

Please visit the firm link to site