Political, security and identity reasons are the motives underlying the collective West’s policy of regime change. The Western powers, led by the USA, through NATO, seek to diminish the power of challengers. They seek to assert the collective West’s political identity and economic interests by keeping rising states in a subordinate position, David Lane writes.

As the armed conflict between NATO/Ukraine and Russia comes to a conclusion, attention turns to its underlying causes. ‘Imperialism’ is a call made on both sides. Over a hundred years ago, Rudolf Hilferding and Vladimir Lenin argued that, to maintain the profitability of capital, the European capitalist countries expanded abroad to annex colonies. John A. Hobson added a political motive: English statesmen sought colonies for personal political status and power. Colonies became profitable markets, a source of cheap materials and labour but also perversely satisfied the ambitions of England’s ruling classes.

Similar arguments are used today to explain the forces underlying the conflict between, on the one side, NATO and its aspiring member, Ukraine, and, on the other, rising countries, particularly Russia. Both sides accuse each other of being ‘imperialist’. Ukraine asserts that Russia seeks to expand its borders to the West through investment which, through lower labour costs, will lead to profit for Russian investors. Following Hobson, a writer in the Atlantic Council

, contends that the Russian leadership has ‘territorial ambitious’ to increase Russia’s land area and to renew ‘the imperial intimacy of the Russian relationship with Ukraine…’.

The Russian side condemns the collective West as politically imperialist. While recognising the collective West’s economic motives, the Russian leadership also relies on its propensity for political domination. Russia is defending itself against the collective West’s imperialism. This becomes clear in President Putin’s speech on September 2022. ‘The West is ready to cross every line to preserve the neo-colonial system which allows it to live off the world …to extract its primary source of unearned prosperity, the rent paid to the hegemon. …’

The Imperial Balance

Leaving on one side the political relations, what evidence is there that Russia and/or the collective West is imperialist?

Due to restraints caused by hostilities, it is challenging to plot the flows and amount of investment between these counterpart economies, particularly between Russia and Ukraine. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) presents comparative data on the portfolio holdings of assets of foreigners

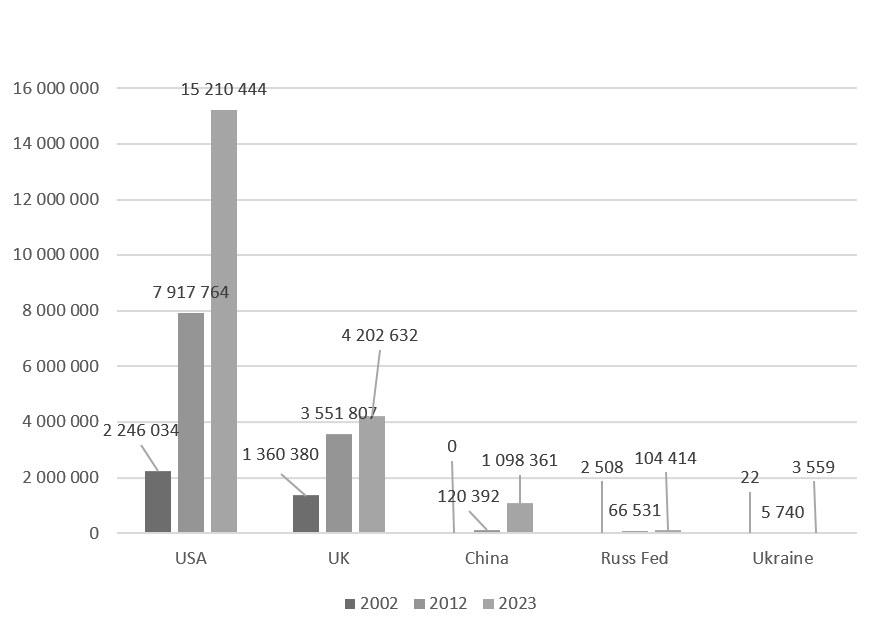

. The data on Figure 1 show the world level of foreign investment for Russia, Ukraine, China, USA and UK for three years chosen (2002, 2012 and 2023). They give a picture of foreign investment (the ‘export of capital’) before and during the Ukraine/NATO/Russian war.

Figure 1. Total World foreign investment of USA, China, UK Russia, Ukraine 2002 2012, 2023 (millions dollars)

No data available for China 2002. For 2023, no data were available either for Russian assets in Ukraine or for Ukrainian assets in Russia.

As far as the ‘imperialist’ thesis is concerned, on a world scale, the core Western states appear to confirm the export of capital thesis. Figure 1 illustrates three points:

- The overwhelming primacy of the USA as a world holder of foreign investment.

- The significant growth of foreign investment for all countries in the period 2002 to 2012.

- The enormous disparity in levels of foreign investment between the advanced Western capitalist countries (here USA and UK) and the former socialist countries (China, Russia and Ukraine).

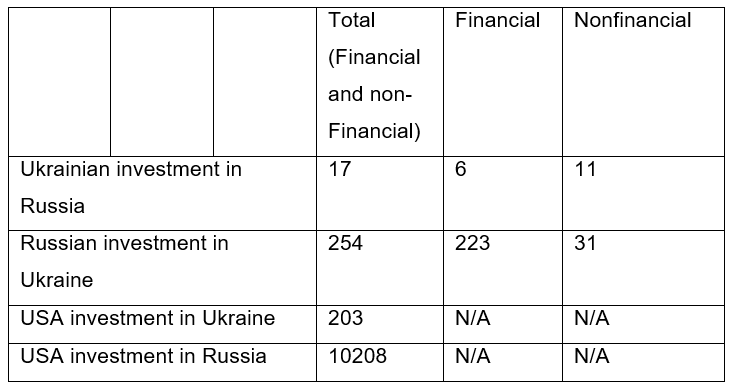

The question remains as to whether Russia ‘exploited’ Ukraine to such an extent that it might qualify as an imperial relationship. Financial data for the period leading up to, during, and before, the NATO-Ukraine/Russian conflict have been supressed and the public cannot have a comprehensive view. In Figure 2, I cite IMF statistics on ownership of portfolio assets in 2001 between the two countries, and USA investment in Ukraine and Russia. 2001 is the latest date for which the IMF database has comparative, though incomplete, data for portfolio investment.

Figure 2. Investment between Ukraine and Russia 2001 (millions of dollars)

Source: IMF Financial Statistics, Table 3.B: (Historical CPIS), as in Figure 1 above.

What then do these statistics tell us about Russia’s, Ukraine’s and the USA’s ‘imperial relationship’? In 2001, Russian investment in Ukraine is 73 times greater than Ukraine’s investment in Russia. In comparative perspective, the USA’s investment in Russia was 567 times greater than Ukraine’s investment. Russia’s investments in Ukraine were 125 per cent greater than those of the USA. Russia clearly was a leading player in Ukraine, surpassing the USA’s investment – though not by a very high amount. Nearly 65 per cent of Ukrainian investment in Russia was in the nonfinancial sector and, in quantitative terms, this was relatively low, whereas 87 per of Russian investment in Ukraine was in the financial sector and was considerable in quantity. However, put in the perspective of American investment in Russia, Russian investment in Ukraine was relatively small.

Russia’s Capital Investment Abroad

One might conclude that Russian foreign investment is not driven by a surplus of capital seeking a market in Ukraine. Figure 2 indicates the higher level of Russian investment in Ukraine to that of Ukraine in Russia. However, the data given earlier indicate that Russia was a very minor figure in the export of capital on a world scale and at a qualitatively lower level than the USA and the UK. Russia has had insufficient domestic capital investment. Study of Russia’s direct foreign investment indicates a preponderant transfer of funds to tax havens. For example, IMF data for the Russian Federation in 2020 record the top inward five origins as Cyprus, Bermuda, Netherlands, UK and Bahamas and the top outward countries in receipt of Russia’s direct investment were Cyprus, Austria, Netherlands, Switzerland and the UK. (IMF data base, Coordinated Direct Investment Survey (CDIS) Such tax havens not only minimise payment of tax, but also are used as a base for the reinvestment of assets. Hence Russian investors may transfer funds to Cyprus and from there invest back in Russia. The advantage here is that they pay tax at Cyprus rates and also retain their assets there. However, such data are not of much use for the purpose of establishing an ‘imperialist’ economic relationship. Tax havens are perverse in preserving personal assets. As noted above, Russia’s level of foreign investment is very low on international standards.

Directions of Trade

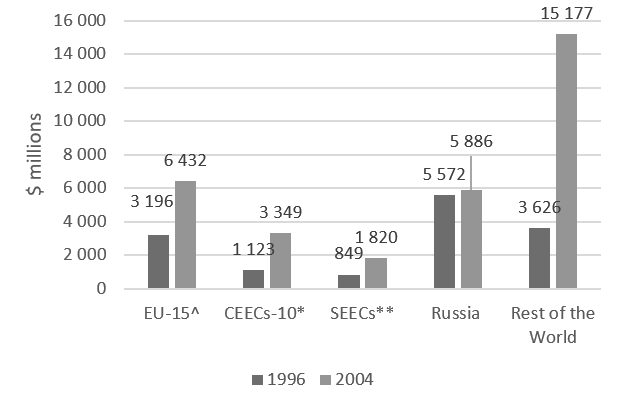

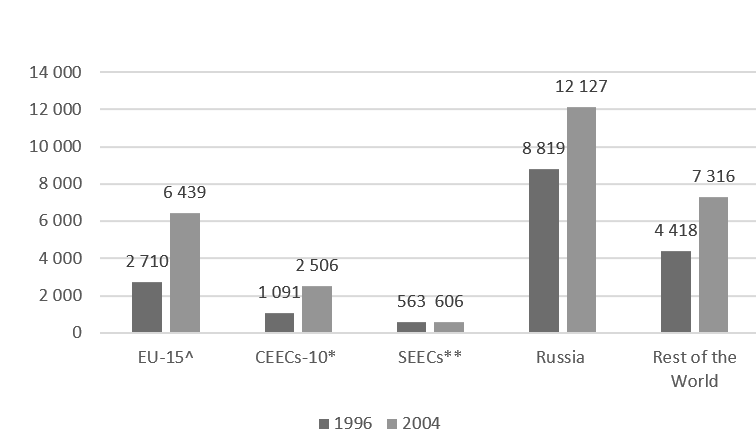

Exploitation between countries may take the form of uneven trade relations in which the imperialist country receives greater wealth in the form of imports than it gives back in exports. Figure 3 shows Ukraine’s exports: to Russia, to various European groups of countries, and to the rest of the world. Later, in Figure 4, I compare them to Ukraine’s imports.

Figure 3. Ukraine’s exports: 1996 and 2004

Data shown in millions of dollars.

Source: International Monetary Fund, Direction of Trade Statistics.

^ EU15 membership in 2004: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and United Kingdom.

* The 10 Central and Eastern European countries (CEEC-10): Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Hungary, Czech Republic and Cyprus.

** The south-eastern European countries (SEECs): Bulgaria, Romania, Bosnia/Herzegovina, Macedonia, Albania, Croatia, Yugoslavia and Turkey.

In 2004, Russia accounted for 16 per cent of Ukraine’s exports (these percentages have been calculated separately and not shown in Figure 3), the EU15, 19.7 per cent, the ‘rest of the world’ 46.5 per cent. As a proportion of Ukraine’s total exports, from 1996, Russia’s share fell sharply and the EU15 experienced a small contraction, while the share of the rest of the world increased rapidly. In absolute terms, Ukraine’s exports to Russia rose slightly between 1994 and 2004, but were outmatched by Ukraine’s exports to the European Union, which doubled and to central and Eastern Europe which also increased considerably.

The ‘imperialist’ interpretation requires the balance of imports from Russia to be considerably less in value terms than Ukraine’s exports. Table 4 shows that imports from Russia rose 37 per cent; however, the share in total imports fell from 50 per cent to 42 per cent, the difference being made up by a significant increase in both imports from the rest of the world. Russia constituted the top country destination in 2004 for Ukraine’s exports (16 per cent) and also was the predominant and growing source for imports, which accounted for 42 per cent of the total in that year. Russia was by far the largest single country origin of Ukraine’s imports (see Figure 4). In both years, Russian imports to Ukraine were far greater than Ukrainian exports to Russia: in 2004, the ratio of Ukrainian imports from Russia to Ukrainian exports was 2.06:1.0 (12,127:5,886). On this measure, Russia was not ‘imperialist’ in its trade relations with Ukraine.

Figure 4. Ukraine’s imports: 1996 and 2004 (millions of dollars)

Data shown in millions of dollars. Source: IMF, Direction of Trade Statistics, cited by Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) ‘The prospect of deep free trade between the European union and Ukraine’, Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), Brussels

The Balance Between Types of Products

How then does the material content of trade to Ukraine fit Russia into the ‘imperialist’ category and how does Ukraine relate to the wider world system? What the Figures above do not show is that exports from Ukraine to Russia were made up of capital-intensive goods (55 per cent in 2002), whereas the exports to the EU25 were composed of raw materials (40 per cent of its exports to this destination). The greater part of Ukraine’s imports from the EU25 (58 per cent) were of capital-intensive goods whereas from Russia they were made up of raw materials (69 per cent)

.

The Centre for European Policy Studies Report (favouring a deep free trade area) regarded Ukraine as having a ‘comparative advantage as a low-wage location with access to both the EU and the Commonwealth of Independent States’ markets’. Indeed, Ukrainian textile and clothing exports to the EU are derived from ‘production networks with EU firms where Ukrainian firms perform labour-intensive operations outsourced from Western Europe’. In 2004, the EU consumed only 10 per cent of Ukraine’s exports of machinery (Russia over 35 per cent) and only around 5 per cent of manufactured articles. The core states of the EU (by importing raw materials and exporting manufactures) were more imperialist in terms of trade.

In terms of current politics, the analysis of the Russia – NATO/Ukraine conflict as an instance driven by ‘imperialism’ is mistaken. Neither Russia nor Ukraine is an imperialist country in the classical sense of seeking markets for investment which cannot be made in the home market. Neither country, in recent history, has, or aspires to create, an empire at the cost of the other. The economic reasoning underlying the ‘imperialist’ paradigm is not a cause of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Should the war end with the partition of Ukraine, it seems likely that the Western part will become a dependent part of the European Union.

Political and Security Issues

Political, security and identity reasons are the motives underlying the collective West’s policy of regime change. The Western powers, led by the USA, through NATO, seek to diminish the power of challengers. They seek to assert the collective West’s political identity and economic interests by keeping rising states in a subordinate position. Enlargement of NATO strengthens the security of the collective West against challenger states. The conflict is not driven by the need of the dominant imperialist powers for expansion to secure a market for investment in ‘colonies’ but is the result of a political competition of economic and political interests, moral values and ideational beliefs. This constitutes the basis of the current clash between China/Russia/rising states and the collective western powers.

The Valdai Discussion Club was established in 2004. It is named after Lake Valdai, which is located close to Veliky Novgorod, where the Club’s first meeting took place.

Please visit the firm link to site