While China achieving its growth target is nothing new, the slowdown in a number of sectors (e.g. real estate and consumer goods) and the deflationary trend in the economy suggest that the reported growth number may be overstated. Worries over the strength and, above all, the sustainability of China’s economic model have not faded. There is also growing doubt about the transparency and credibility of China’s statistical machinery. Lastly, 2025 will necessarily be affected by changes in the US-China relationship, which is currently the leading driver of uncertainty.

Where is growth coming from?

The first “surprise” was industrial production, up 6.2% in December after increasing by 5.4% in November, and in particular manufacturing production, buoyed by solar panels, the transport sector (notably cars and spares) and household goods. It seems that, in anticipation of the first tariff hikes and restrictions on free trade more generally, US firms have built up significant inventories, leading to a 16% surge in Chinese exports to the US in December. Foreign trade thus boosted industrial production and made a positive contribution to 2024 growth, adding 1.5 percentage points (pp) – a level not seen (excluding the post-pandemic recovery of 2021) since 2006. China’s trade surplus reached an all-time high of nearly $1 trillion in 2024, by far the largest surplus ever recorded by any country.

On releasing this fourth-quarter and full-year 2024 data, the Chinese authorities also took the opportunity to point out that their monetary and fiscal support efforts were beginning to bear fruit. It is important to acknowledge that the government responded to the slowdown in growth in the first half of the year with a slew of announcements to revive consumer and investor confidence. In December, the last meeting of the Politburo concluded with the authorities committing to implement “more proactive” fiscal policy and “sufficiently accommodative” monetary policy. This very unusual language reflects a genuine change in tone on the part of the authorities and a recognition of the existence of structural factors holding back the economy, starting with weak consumer spending. This press release has yet to be translated into any new stimulus measures, which are more likely to be unveiled during the parliamentary sessions in early March.

The authorities had already announced a 10 trillion yuan plan (around $1.4 trillion) in early November to help get local governments back on an even keel. On top of this, a programme of consumer subsidies was widened to cover more products including not only televisions, phones and tablets but also household goods (microwave ovens, dishwashers and rice cookers), in addition to programmes aimed at vehicles (combustion engine or electric), pay rises for civil servants and monetary policy easing (interest rates, reserve requirement ratio and mortgage rates). Ultimately, the scale of the support package, which equates to around 10% of Chinese GDP (albeit spread over three years), almost seems out of proportion to China’s apparent growth trajectory: while growth was indeed below the 5% target at the point when the authorities unveiled their package in the third quarter of 2024, it was not far off. Even during Covid, when official growth slowed much more sharply (coming in at 2.3% in 2020), the government did not provide the economy with such strong support.

Why the doubts?

Reading China’s statistics leaves one with the impression that the model does not completely add up. . How does one reconcile this 5% growth and its breakdown (with consumer spending adding 2.2 pp, investment 1.3 pp and foreign trade 1.5 pp) with the more negative signals sent by other economic data points? And, above all, why are the authorities working so hard to support what looks like to be an already high level of growth? Three inconsistencies can be identified, the first of which is detailed here; the other two can be found in the full version of this analysis.

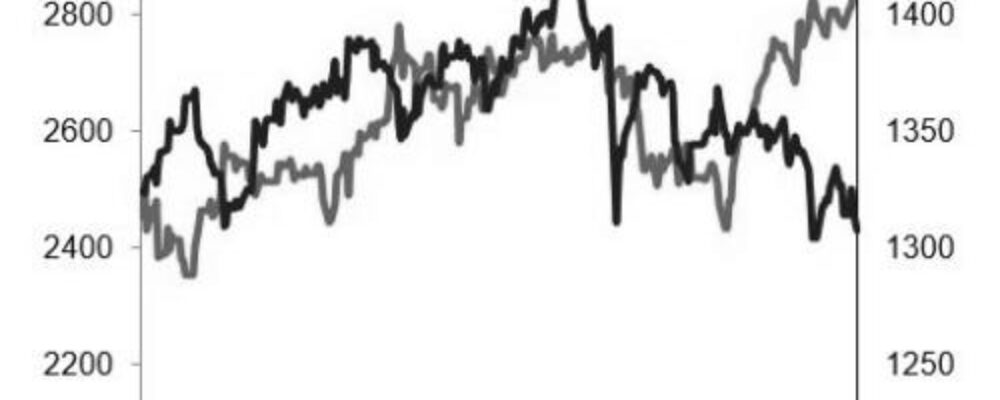

The first inconsistency is the mismatch between growth and inflation. Every year, the authorities announce an inflation target – usually 3% – at the same time as the growth target. Yet, while the growth target is met every year, this inflation target has been met just five times since 2000. In reality, if one were to delve into the annals of economic history, it would be hard to find any country without a fixed exchange rate regime that has known such strong and stable growth as China since 2000, without that growth fuelling higher inflation. One can take the view that the Chinese authorities want inflation to remain low because they want the economy to be price-competitive above all else. The reason inflation is so low lies in wage restraint by Chinese firms – both public and private – and the existence of a huge pool of labour fed by the rural population and migrant workers. It is kept low by high levels of competition within the economy, particularly in the private sector, which also drives prices down, since firms tend to be price-takers rather than price-makers in markets. Lastly, China’s interventionist government can control price trends, notably through the existence of strategic inventories and reserves (of metals, oil and agricultural products).

However, since 2020, low inflation has appeared to be something the Chinese authorities have been forced to put up with rather than something they have opted to maintain. It reflects the lack of domestic demand seen in household consumption numbers. There are a number of factors explaining consumer behaviour. First off, Covid hit the labour market a lot harder than official unemployment statistics suggest, with 47 million jobs destroyed during the pandemic; youth unemployment in particular highlights just how difficult it is for the labour market to absorb even the most highly qualified new entrants. The state of the labour market, the scars left by the zero-Covid policy and, of course, the situation in the real estate sector triggered a crisis of confidence among households, altering consumers’ trade-offs between spending and saving. The result was an interruption in the very slow shift in the balance between consumption and investment – a shift that is necessary if China is to successfully transition to a growth model driven by domestic demand rather than foreign trade and investment. The severe real estate crisis, from which China is still struggling to emerge three years after it began, is thus fuelling deflationary pressures in two ways.

And, while Chinese firms could always count on strong external demand to soak up excess production they were unable to sell in the domestic market, it looks like 2025 will raise many questions about the kind of trading environment with which China will now have to contend.

Questions for 2025

For China, the return of Donald Trump is a potential source of much instability. This could be both a threat and an opportunity. The threat is mainly in the economic arena. Hiking import tariffs on Chinese goods was one of Trump’s campaign promises. And while the Republican line, embodied in particular by the new Secretary of State Marco Rubio, is harder than the Democrat line, growing protectionism with regard to China is one of a small number of issues to enjoy bipartisan support. This means Trump could have Congress’s full backing for his measures, Cwhich could take various forms: higher import tariffs – initially an extra 10% but eventually as high as 60% if Trump sticks to his guns; continued restrictions on exports of high value-added technology products; and sanctions on Chinese firms. China expects and is readying itself for these announcements, and for the US’s stance to harden. It knows it must look beyond the “golden age” of globalisation, from which it had benefited so handsomely since joining the WTO in 2001, though this has not stopped the authorities making various attempts to offer the new administration an outstretched hand. Vice President Han Zheng attended Trump’s inauguration and has had many meetings with the new team tasked with overseeing trading relationships and the US-China business community.

Ever since 2018, the authorities have been preparing to “decouple”, notably through a strategy of “dual circulation” aimed at limiting China’s reliance on imports while supporting exporters. These preparations have taken various forms. Chinese firms have already relocated parts of their value chain to third countries, chiefly Mexico and Vietnam. The US increasingly sees these countries as back doors for Chinese goods, which means they in turn could come under pressure to reduce their exposure to China on pain of facing additional restrictions or import tariffs that would directly affect Chinese firms benefiting from the system.

Decoupling has also translated into huge investment in sectors in which China is behind the curve technologically speaking, and in which the US would like to keep China at bay by controlling the exports of US firms (as well as, if it can, firms from other countries) in strategic sectors such as artificial intelligence, semiconductors, aerospace and military hardware. It is hard to know with any certainty how much progress China has made in catching up in these areas. It still appears to be heavily dependent on imports of huge volumes of the most advanced integrated circuits and semiconductors from Taiwan and South Korea. However, the unveiling of DeepSeek, a Chinese chatbot developed – according to the official narrative – with reduced resources and minimal investment, shows that that China is far from being left behind and continues to pursue its goal of achieving strategic autonomy.

The main opportunity lies in the geopolitical arena, where the America’s radical, imperialist positions (on Greenland, Panama and Gaza) and its withdrawal from the multilateral (the Paris Agreement, the WHO, the Human Rights Council) and bilateral (dismantling of USAID) architecture could be an opening for China to assert its will. Indeed, the empty space left by the United States could leave China as the leading contributor to some institutions, starting with the WHO, giving it more of a say in the management of these multilateral structures that do so much to propagate standards and ideas. More than ever before, China is also likely to position itself as a protector of the Global South, which is still disorganised and not completely aligned with China’s stance but which US actions against free trade and international aid, on which many countries depend, could help unite.

As we have seen, China has stated its willingness to negotiate. This is not incompatible with its latest statements and measures adopted in response to US tariff hikes. A “super deal” in which Trump emerges as the winner is not impossible. It remains to be seen, of course, how much China might be willing to put on the table – and, conversely, how it might react if trade tensions escalat2.

Conclusion

It is a weakened China that now faces a provocative and combative Donald Trump.

Covid-19 left profound scars on the Chinese economy and society, with the real estate crisis, the crisis of confidence among households, manifested by the failure of domestic demand to pick up, and huge levels of sometimes ineffective local government debt revealing the limits of China’s fiscal system. In reality, the country’s entire economic system seems to have passed its peak, revealing some hard-to-conceal inconsistencies. Meanwhile, the Chinese manufacturing complex is triumphant, enjoying the luxury of historic surpluses. This is not such a paradox: China is scouring the rest of the world for the consumers it lacks at home. With protectionism back on the agenda, led by the US, this is a dangerous game – but one that most countries which no longer benefit from the status quo, and which understand that cheaper Chinese products do not replace jobs or industrial activity, are now playing.

In this emerging new world, China can still wield great power, but to do so will require swift and radical reforms to address structural issues specific to the Chinese model: land distribution, free movement of domestic workers and development of safety nets (without falling into the kind of dependency that Xi Jinping so detests) supported by a tax system that allows for a little more redistribution in a country where inequality has skyrocketed. Above all, China will need to inject fresh confidence into disenchanted households who see the social contract – at the heart of the regime – as being increasingly neglected.

This analysis is an abridged version of a study that can be found in full here (only available in French).

“Crédit Agricole Group, sometimes called La banque verte due to its historical ties to farming, is a French international banking group and the world’s largest cooperative financial institution. It is France’s second-largest bank, after BNP Paribas, as well as the third largest in Europe and tenth largest in the world.”

Please visit the firm link to site