The DeepSeek phenomenon

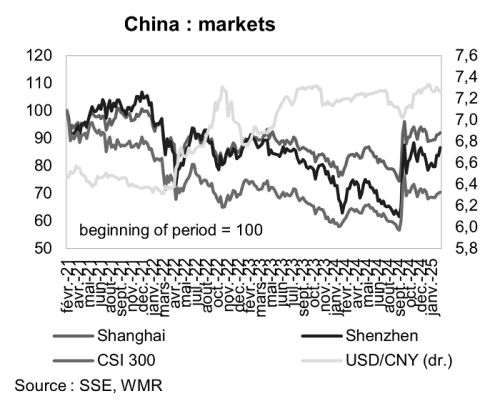

The first trend, as yet unconfirmed, is a “DeepSeek effect”. Unveiled on 20 January, this artificial intelligence, officially developed on a shoestring budget in comparison to the amount invested by the Americans in ChatGPT and Perplexity, has set share prices in the Chinese tech sector – which has had a rough ride over the past few years – soaring.

First, at the end of 2020, there was the unceremonious fall from grace of Jack Ma, the iconic boss of Alibaba who became a thorn in the government’s side because of his vocal public criticism of the Chinese financial system after the IPO of Ant, his group’s financial services subsidiary, was scrapped. Then the regulatory screws were tightened in summer 2021, bringing some sub-sectors (notably online education) to their knees. And let’s not forget investigations into other big names like Tencent and Didi for abuse of market power, mishandling of personal data and monopolistic practices. Chinese tech firms keen to conquer international markets and be listed on the stock exchange, particularly in the United States, also had to give up these ambitions.

This was a time when it was no longer a good idea to flaunt one’s wealth or success, especially if they appeared to have been amassed too quickly and at consumers’ expense. The US’s obvious dominance in artificial intelligence and China’s reliance on chips and integrated circuits from South Korea and Taiwan suggested that China had fallen behind, and that efforts to rein in the new technology sector and its leaders would make it hard for it to catch up again.

Yet, on 17 February, there was Jack Ma, welcomed back into the circle of business leaders from up-and-coming sectors who had been summoned to the Great Hall of the People for a symposium chaired by Xi Jinping himself. The purpose of this orchestrated gathering? To show off the government’s support for the private sector and the latest Chinese innovations and encourage public corporations and private companies to adopt the latter as quickly as possible. Since then, not a week has gone by without a major company (Huawei, Tencent, Baidu) or city (Changsha, Zhengzhou, Shenzhen) announcing some new use for DeepSeek, giving markets a major boost.

Markets appear to want to believe this message. Last September, news of more substantial government support for the economy also unleashed a wave of euphoria on Chinese stock markets. Since then, the effect had subsided slightly, reflecting disappointment at the lack of tangible action, particularly in terms of support for consumer spending. The conclusions of the “Two Sessions”, China’s main annual political gathering due to kick off in Beijing this week, will be another test as to whether or not investors have bought into the government’s strategic priorities for the economy and whether the “DeepSeek effect” has legs.

China/US decoupling is affecting markets too

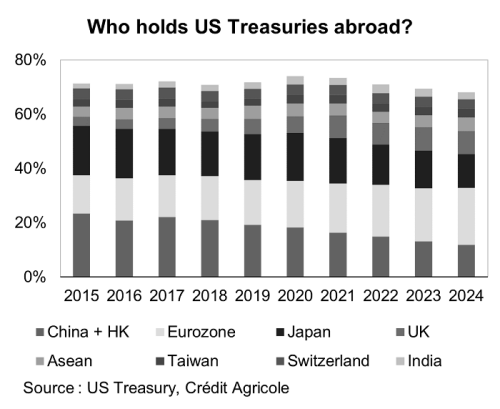

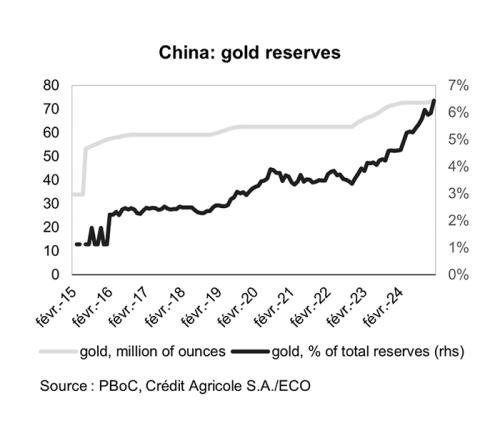

The second trend – this one deep-rooted – is the reduction in Chinese holdings of US debt. China’s (including Hong Kong’s) share of US bonds held by foreign investors has fallen to 11.9%, its lowest since 2009 and half what it was in 2015. What this means is that the value of sovereign bonds held by Chinese investors declined by $57 billion between 2023 and 2024, and has fallen by $500 billion since 2015, to $759 billion. This reflects China’s desire to diversify its asset holdings, particularly when it comes to its currency reserves. For example, the country has considerably built up its gold reserves, which now account for 6% of its total reserves.

However, these figures only partially reflect reality and must be qualified: although China has almost certainly sought to limit its exposure to US debt since 2010, it continues to hold US bonds through accounts in other countries (notably Belgium and Luxembourg, via depositaries Euroclear and Clearstream) that do not count towards its official holdings of US debt, as well as also investing in US equities. This means it is impossible to say how much US debt China really holds. One thing is certain, though: China wants to officially show itself as being less reliant on the United States.

Diversifying and securing investment

This desire to diversify is also reflected in the reform announced at the beginning of this year aimed at attracting more medium- and long-term capital to Chinese markets.

The reform applies to insurers, pension funds and mutual funds. It consists of three key measures:

- Increasing the proportion of state-owned insurance companies’ capital investment that goes into A-shares (to at least 30% of new premiums)

- Increasing the amount of funds invested in capital markets by the National Social Security Fund

- Leveraging mutual funds (by encouraging them to increase the tradable market value of their holdings of A-shares by at least 10% a year over the next three years)

Up to now, Chinese household savings have mainly been captured by the real estate sector, with relatively little investment in financial instruments. The challenge, then, is to offer products designed to meet a medium- or long-term investment goal, the underlying assumption being that the real estate sector is unlikely to ever return to its 2021 levels (in terms of its buoyancy and relative contribution to growth and GDP). There is also the demographic challenge in a country whose population is set to age and decline, and where the twin long-term challenge of paying for older people’s pensions and healthcare will be heavily reliant on putting people’s savings to work.

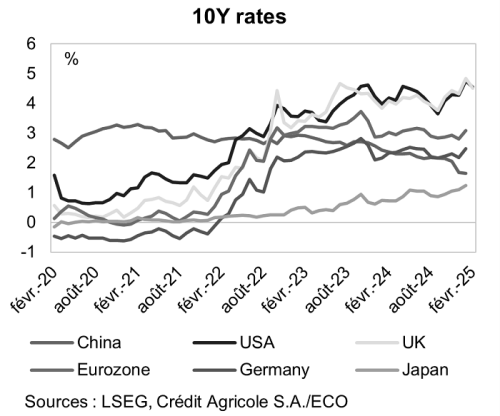

Chinese long yields have also fallen sharply over the past few months. Driven down by accommodative monetary policy and a deflationary environment triggered by the real estate crisis and weak consumer spending, they have served as a safe haven. China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, is thus seeking to steepen its yield curve in an international environment where advanced country bonds offer a better risk/reward profile than Chinese bonds. Despite being relatively protected from volatility by exchange and capital controls, China has seen capital outflows over the past few months, reflecting a shift in the kinds of trade-offs made by domestic and foreign investors. Offering new products, other than government bonds, with higher returns would also help retain Chinese savings by making it more attractive to invest them.

Reforming Chinese markets is one of the major structural challenges usually cited as being necessary if China is to evolve into an advanced economy. With lacklustre performances often decorrelated from the real economy, Chinese markets have encountered plenty of turbulence since 2021, connected with technology and real estate stocks in particular. Will the advent of DeepSeek and the authorities’ efforts to show more support for the private sector be enough to attract investors who have tended to abandon Chinese markets? Another point in China’s favour is the fact that, amid falling markets, Chinese shares are cheap, particularly when compared with their US counterparts. With China in the grip of a crisis of confidence mainly resulting in households accumulating precautionary savings, the challenge is to convert those savings into investments in up-and-coming sectors. While this might not solve China’s domestic demand problem in the short term, it is aligned with Xi Jinping’s vision of a modern China at the cutting edge of technology.

“Crédit Agricole Group, sometimes called La banque verte due to its historical ties to farming, is a French international banking group and the world’s largest cooperative financial institution. It is France’s second-largest bank, after BNP Paribas, as well as the third largest in Europe and tenth largest in the world.”

Please visit the firm link to site